A kid growing up drinking lead in water is less likely to graduate from high school or go to college. The child consuming the poisoned water is more likely to be unemployed later. And a child consuming lead during their childhoods are more likely to commit crime.

In 2018, research by Robert J. Sampson and Alix S. Winter linked an increase in lead in water to a higher likelihood of criminal behavior.

“We have presented new evidence of a consistent link between childhood lead exposure and antisocial behavior in both childhood and later adolescence, with an estimated magnitude of effect greater than many standard predictors in criminology,” they reported.

New York-based attorney Corey Stern relied on the proven effects of lead on kids in two lawsuits filed against the City of Jackson and State of Mississippi on Oct. 19, 2021 on behalf of a group of children in Jackson, Miss., due to beliefs that the capital city’s water system has hurt them and stunted their future development.

The lawsuits were identical, but one of them has one plaintiff seeking $5 million in compensation, and in the other 600 plaintiffs are demanding nearly $3 billion in compensation.

In an interview with the Mississippi Free Press on Dec. 13, Stern, who was the court-appointed lead counsel in a similar case in Flint, Mich., said the number of plaintiffs in the Jackson case has almost doubled since the initial filing, and he expects a further increase.

“Since that time, we’ve been retained by another 400 kids; we represent over a thousand children right now,” Stern said over the phone.

“For each case, we hope to achieve an award for them that comes close to compensating them for what they’ve lost from being lead poisoned.”

How Lead in Water Affects Children

When Corey Stern from New York talks about Mississippi children being poisoned and mentally damaged by lead in their drinking water, he is relying on science, not conjecture. And like many systemic harms that limit young people’s potential and health, the ingestion of lead is a systemic issue passed along by societal inequities and poverty.

Lead poisoning leads to brain damage that limits educational success and puts children of color, especially, on negative tracks that can lead to crime and other harmful outcomes. Those kids are mostly likely to be growing up in the conditions in today’s society that cause lead poisoning and its symptoms.

In a study released in September 2021, researchers found that elevated blood lead levels are more prevalent in high-poverty areas and ZIP codes with a predominantly Black population. Researchers Marissa Hauptman, Justin K. Niles, Jeffrey Gudin and Harvey W. Kaufman reiterated that there is no safe level of lead in the water, and that “children residing in zip codes with predominantly Black non-Hispanic and non-Latinx populations had higher odds of detectable blood lead levels.” They relied on data from 1,141,441 under the age of 6 in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia who participated in the study.

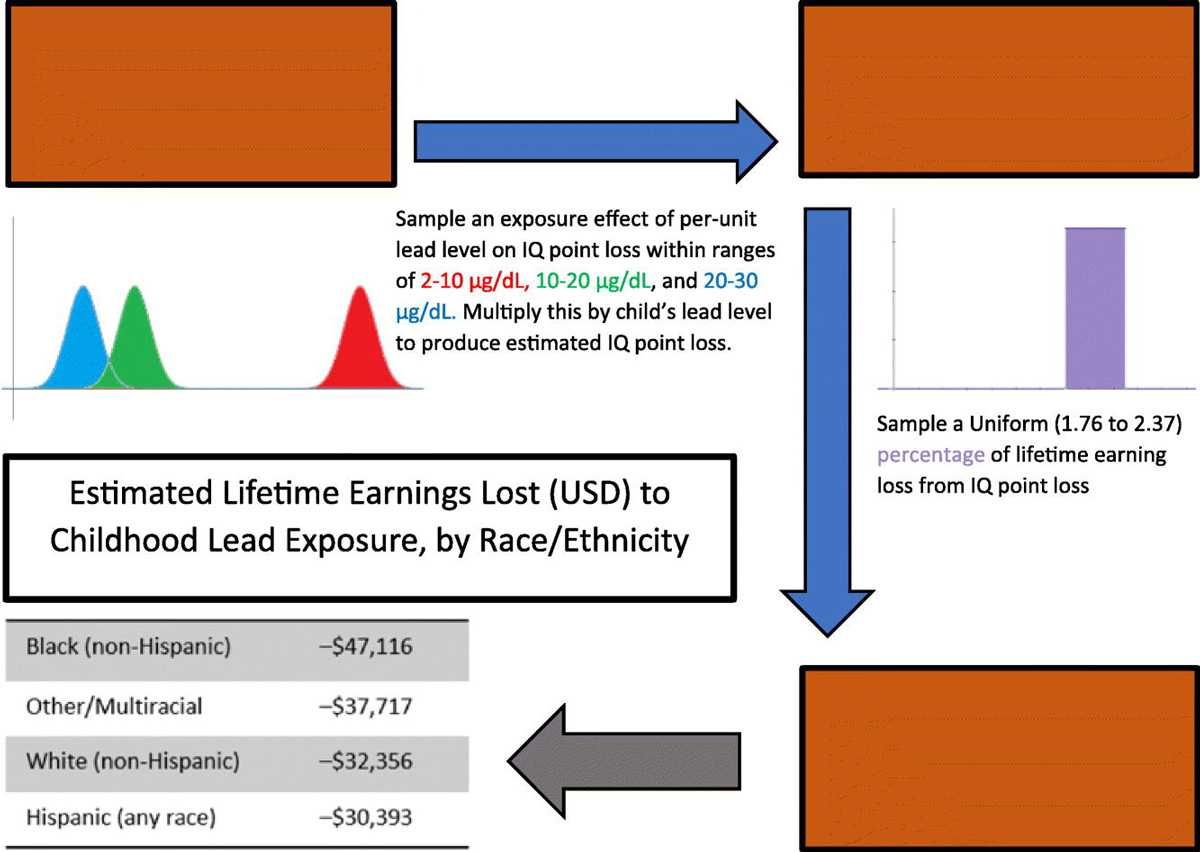

Researchers reported in the Science of the Total Environment Journal in July 2021 that Black infants experienced a 46% to 55% greater average estimated loss of grade-school IQ points from blood lead than Hispanic or white infants.

Authors Joseph Boyle, Deniz Yeter, Michael Aschner, David C.Wheeler

“We report two aspects of the substantial national costs attributable to lead exposure in just the second year of life alone, which disproportionately impact predominantly African American black infants from continuing legacies of environmental racism in lead exposure,” they explained.

“Our findings underscore the remarkably high costs of recognized hazards of blood lead, even at the lowest levels, and the importance of primary prevention regarding childhood lead exposure.”

In the interview, lawyer Stern lamented the compounded effect of lead in drinking water on children in Mississippi’s capital city and accused both state and city leaders, white and Black, of negligence for not doing anything about the open secret.

“So a kid that’s lead-poisoned is brain-damaged,” Stern told the Mississippi Free Press. “It steals their potential.”

“And so whoever did that to the kid has to pay the kid for that, and that’s going to be times a thousand or 2,000 or 5,000 or however many kids we end up representing.”

Science writer Alexandria Ossola wrote on the health dangers of lead in water in Popsci.com in 2016.

“When cells in the brain absorb lead, it tends to affect the frontal cortex, the area responsible for abstract thought, planning, and attention, and the hippocampus, essential to learning and memory,” she argued. “(L)ead is toxic, and if it makes its way into the still-developing brains of young children, many of the effects can be permanent.”

“Lead can change how signals are passed within the brain, how memories are stored, even how cells get their energy, resulting in life-long learning disabilities, behavioral problems, and lower IQs.”

What Happened in Flint, Mich.

Corey Stern successfully represented more than 2,500 children in Flint, Mich., over contaminated water. On Nov. 10, the U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of Michigan, Judith E. Levy, awarded $626 million to the plaintiffs in that case.

The problem of lead in Flint’s water began in April 2014 when city officials switched the public water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River to save money. At the time, that city was facing financial difficulty. Then-Michigan Gov. Richard Dale Snyder’s emergency manager decided to change the water source as a cost-cutting measure. For decades, the slightly majority-Black City of Flint had been paying $1 million monthly to the Detroit Water and Sewage Department.

“And one of the first decisions that the emergency manager made was to switch from the DWSD (to a) different conglomerate called the (Karegnondi Water Authority) KWA,” Stern explained in an interview on the Chicago Bar Association’s @theBar podcast in August 2021. “It was being built, however, and so it wasn’t ready to actually service Flint.”

“When the old Team DWSD found out that Flint was going to take its talents to a new team, they canceled the contract, but Flint was stuck for a period of time without a water source, or they were going to be stuck without a water source,” he added. “They had the option to either stay with DWSD or utilize the Flint River, and they made the decision to switch to the Flint River temporarily while the KWA, the Karegnondi Water Authority, was being built.”

The new source was, however, more polluted and needed a different preparation to ensure that it was fit for transfer into homes.

“It’s problematic because, beyond the pollution in the water, the water could have been used—the Flint River was a viable water source,” Stern said on the podcast. “But it would have required significant treatment from professionals for all of the bad stuff that existed in the water because it was a surface water source, which means that the composition of the chemicals in the water changes often because of rains and storms and winds.”

“And so it’s not that it couldn’t be used, just that if it was going to be used, it had to be used right, and it wasn’t,” Stern said.

One of the results was that Flint’s water had a corrosive effect on the lead pipes underground, causing the dangerous metal to leak into the drinking water and cause problems, especially for children.

“Lead poisoning in children has serious, long-term effects on their health, including the risks of impaired cognition, behavioral disorders, delayed growth and development, learning issues, and hearing and speech disorders,” Stern’s firm, Levy Konigsberg, LLP, wrote in a news release announcing the settlement in the Flint case.

“Scientists agree that there is no level of lead that is safe and that many of the injuries suffered by these children are likely to be permanent and lifelong.”

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences explained that “despite progress in reducing lead exposure in U.S. communities, elevated blood lead levels remain an issue for children, particularly those living in poorer areas. Disparities in who is harmed by lead contamination persist.”

Attorney: Jackson’s Case Worse Than Flint

The case in Jackson is worse than what occurred in Flint because of how long it had lasted and the size of the population it affected, Stern told the Mississippi Free Press. Flint has a population of more than 80,000 compared to 150,000 for Jackson, and both have a majority-Black population.

“It’s worse because Flint started in 2014, and they switched back to good water in 2015,” Stern said. “Here (in Jackson, Miss.), we know, at least in 2015—but likely for longer—all the way through now, the water’s still bad.”

“And so, in Flint, even if everybody drank as much water as they could, they were only drinking bad water for 14 or 15 months,” the attorney added. “In Jackson, they’ve been drinking bad water, in some instances, for their whole lives.”

Compared to other cases he had handled, Stern said the Jackson case was unique, but not because it involved lead pipes. There are 6 million to 10 million lead service lines across the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency reports.

“It’s not unique to have an infrastructure that is comprised, on some level, of lead pipes,” he said. “What is unique is that the folks in Jackson, and on a larger scale, the state, hid this information from the people in Jackson, and they lied to everybody when people started to understand what had happened.”

“And so the uniqueness is in the lies and the deception and the ugliness that they thought a community that was poor and primarily black would not stand up for itself and would not realize that they were being lied to.”

Stern stated that his work in Flint exposed the need for advocacy in communities facing lead poisoning across the country.

“Over the course of four or five years in Flint, I learned about a lot of communities that were as bad or worse than what was happening in Flint,” Stern said in the interview. “And so, it really was an organic process that happened through my research and studying of Flint that led me to Jackson. “

The various children Stern’s firm is representing have faced different impacts and will need different compensation levels, he said.

“And so kid A may be affected in one way, and kid B may be affected in another way, but for all of them who have been affected, none of it is their fault, and there’s plenty of blame to go around,” he said.

Stern alleged that since 2014, and possibly earlier, kids in Jackson have been drinking water tainted with lead and are becoming “lead-poisoned.”

“Which means they’re becoming brain-poisoned, and it’s been going on for at least seven years,” he accused. “The City knew; the State knew, the EPA knew, and nobody’s done anything about it.”

Mother: ‘How Could It Have Gone On For So Long?’

J. W. is a minor who is suing over lead in Jackson’s water. J.W.’s mother is Amanda Williams. In a Levy Konigsberg, LLP, press release, Williams expressed relief at seeing the Jackson case moving forward.

“I have always loved this city, but Jackson officials have shown little respect for my family and children living here,” she said. “How could the people we elected to help us do so much harm to us instead? And how could it have gone on for so long?”

“We need to put an end to this injustice, which is why I’m so proud to have my child represented in this fight for equality.”

Mississippi State University Associate Extension Professor Jason Barrett works at its Water Resources Research Institute. He told the Mississippi Free Press on on Dec. 17 that having lead as water-service lines is not unusual. He said that before Congress’ passage of the Safe Drinking Water Amendment Act on July 19, 1986, lead was what communities used in different products because of its durability and flexibility, and it was used for faucets, water lines and goosenecks.

“People were just using a good product that was legal,” he said. “So the fact that we’ve got the infrastructure in Mississippi has got lead in it, that’s no surprise, and it’s nobody’s fault.”

“At the time when most people were using it, it was the greatest thing since sliced bread—everybody wanted to use it,” he added. “Recently in the past decade or more, we’ve really seen the negative effects on it and then also how it really affects younger children.”

He explained that water systems had included measures to limit the impact.

“As a corrective measure, most public works (departments) have some type of corrosion control, which we try to reduce or eliminate that leaching of any lead in the water,” Barrett said. “The systems have made strides to try to account for lead being out there.”

“Would it be great if we could snap our fingers and be done? Yeah, sure. That’d be wonderful, but it might not happen,” he added. “We’ve got a lot of systems that may not have the resources, financially or, you know, physical capacity with people to do it, so it may take a little time.”

The professor explained that the Mississippi State has a program called SipSafe that seeks to help people to learn how to reduce the amount of lead in the water they drink.

“If we sample it, if there’s lead, you know, what are some things you could do, you know, like running your line five seconds, 30 seconds, one minute in the mornings after that overnight stagnation just to reduce it,” he explained.

Defendants: Wrong Decisions and Negligence?

The City of Jackson, Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba, former Mayor Tony Yarber, former Public Works Directors Kishia Powell, Robert Miller, and Jerriot Smash, the Mississippi State Department of Health, Mississippi State Department of Health Senior Deputy and Director of Health Protection Jim Craig, and Trilogy Engineering Services LLC are defendants in the two cases that Stern filed on Oct. 19.

Based on various orders that U.S. Southern District of Mississippi Magistrate Judge LaKeysha Greer Isaac granted on Dec. 2, 3, and 8, 2021, the defendants have until Jan. 12, 2022, to respond to the complaint involving one plaintiff.

The lawsuits accused them of making wrong decisions or negligence concerning protecting the public from drinking water with lead in the City of Jackson.

In a Tuesday, Dec. 14, 2021, emailed statement to the Mississippi Free Press, City of Jackson Attorney Catoria P. Martin said that her office, representing the City, Mayor Chokwe Lumumba and former city officials, does not comment on pending litigation. The Mississippi Attorney General’s office, representing the Mississippi Department of Health and Craig, similarly declined comment in a phone call on Tuesday, Dec. 14.

When the Mississippi Free Press reached out to Miller, the public-works director for the City of Jackson from October 2017 to July 2020, he said, “I have read the lawsuit, and I am preparing to participate in its defense.”

Yarber, mayor of Jackson from April 2014 to July 2017, pointed this reporter to the city attorney’s office when reached on Tuesday, Dec. 14. “There is a lot I could say, but I’m not going to say, so I’ll let Jackson’s attorney handle that,” he said on the phone.

Trilogy Environmental Services LLC’s attorney, Dennis Jason Childress, did not respond to repeated emails on Monday, Dec. 13, Tuesday, Dec. 14, and Wednesday, Dec. 15, for comments on the case.

The Mississippi Free Press reported in October on the lawsuit alleging that Trilogy Environmental Services, LLC, in 2014, recommended a soda ash treatment system rather than liquid lime, though soda ash clumps under high humidity conditions like the City of Jackson, requiring additional system upgrades to treat the water properly.

EPA’s Report on Lack of Compliant in Jackson

The EPA’s Administrative Compliance Order with the City of Jackson dated July 2021 included the lack of compliance in the requirement for the management of the level of lead in the water system.

The EPA reported that the City’ of Jackson’s water system, after monitoring in January-June 2015, January-June 2016 and July-December of 2016, failed lead level tests, exceeding the “lead action level of 0.015 mg/L.”

“MSDH later extended the completion date to December 2019; yet, the City failed to install (optimal corrosion control treatment) at the J.H. Fewell (Water Treatment Plant) in accordance with the State’s deadline,” the EPA stated. “The City subsequently conducted an OCCT study amendment in 2021 and presented its results and recommended source water treatment to MSDH in a February 2021 report.”

The EPA added that “MSDH accepted the results and recommended the source water treatment plan on June 4, 2021,” and further stated that the problem remained unaddressed at the J.H. Fewell Water Treatment Plant at the time of the release of the administrative order in July.

How Jackson’s Lead Problem (May Have) Started

The lawsuit Corey Stern filed in October noted that in 2014, then-interim Director of Public Works Willie Bell warned city officials that the high pH from the well-water source of water in the capital city was stripping the pipes of the coating and casting lead in lead pipes into the drinking water. However, at this time the level was not above the danger level, though increasing.

In spring 2014, the plaintiffs said that then-Mayor Yarber ordered the switch from well water to water from the “highly corrosive” Pearl River and Ross Barnett Reservoir, which the city could not properly treat.

It accused MSDH officials of conducting insufficient testing in its findings of high levels of lead in Jackson water in June and July of 2015, “greatly underestimating the threat.”

“Quietly, Jackson switched back to well water as a primary drinking source in August 2015,” the lawsuit said. “Tragically, MSDH and Jackson officials failed to warn Jackson’s citizens, including plaintiff and plaintiffs’ family, of the issues with corrosive water from the river/reservoir until January 2016, five months after it was no longer in use.”

“The Plaintiffs will never be the same as a result of the Defendants’ actions and omissions,” the suit said. “Plaintiffs have and will always have cognitive deficits; plaintiffs will have lower earning capacity than their peers; and plaintiffs will feel shame throughout their lives as they struggle to keep up with classmates, family members, and, eventually, coworkers.

Also see Kayode Crown’s followup: Seeking Solutions To Protect Mississippi Children From Lead Poisoning.