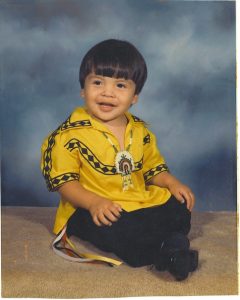

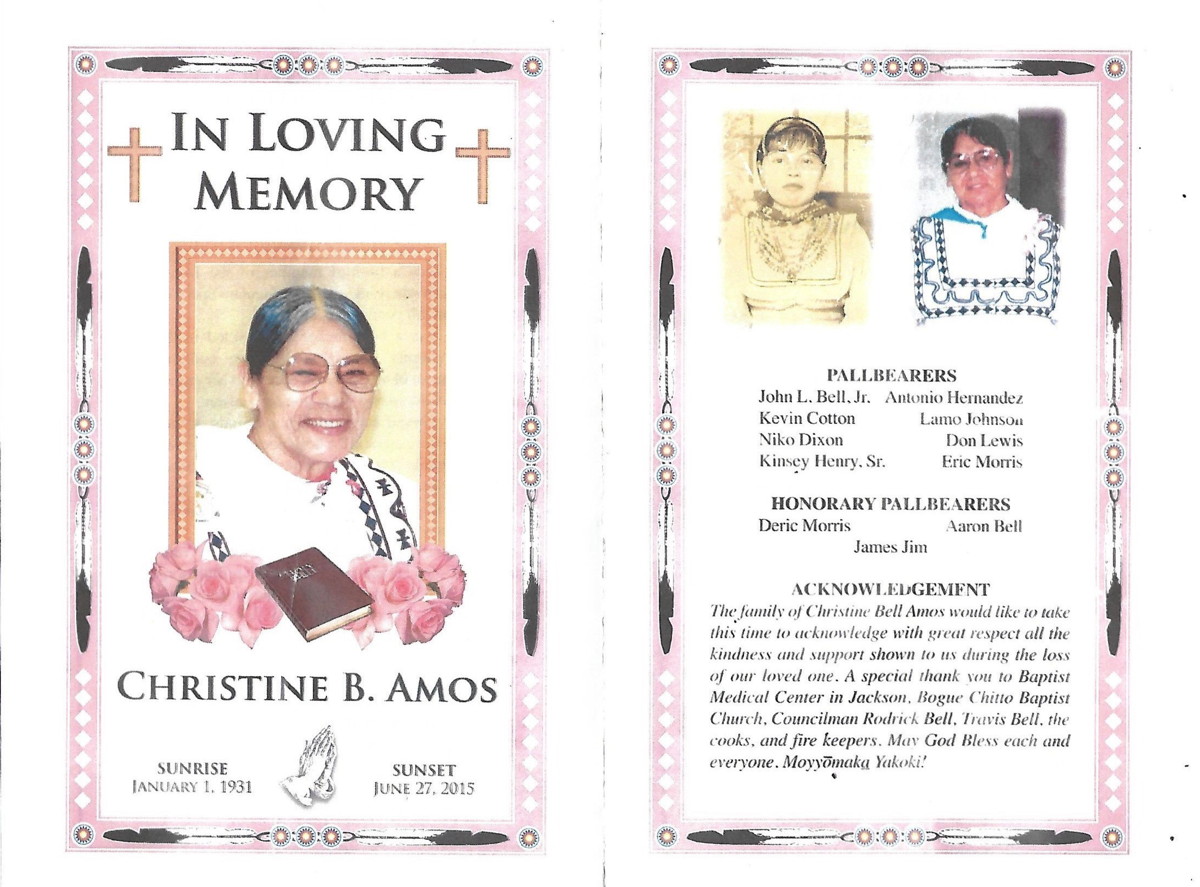

I lost my paternal grandmother in 2015. Gram didn’t speak very much English but understood it enough to get by. She was one of the very few people I knew in my life who spoke 100% fluent Choctaw, and it was always pure joy for me to listen to her speak as a teenager living in Alabama at the time. I had lost a part of my fluency after moving away from the Choctaw Indian Reservation in Neshoba County, Mississippi, when I was 11 years old.

“Achukma ish antah hoh?” she would ask whenever my younger brother and I came to visit from Alabama. That’s “Are you doing well?” in English.

As a young man, I didn’t realize my Choctaw fluency was waning when I was speaking only English. When I visited Gram back in Mississippi for summers and holidays, I attended Bogue Chitto Baptist Church services with her singing hymns like “Amazing Grace” and listening to sermons in both languages. I could compare the words in the English hymnal with the melodies I heard in Choctaw.

I even started to recite the one Bible verse she made us kids learn while she babysat us in her home: Chan 3:16. (There is no name equivalent so chapters were just phonetically spelled in the Choctaw Bible). That helped raise my fluency with each visit. So did being around my father’s side of the family in the Bogue Chitto (Bok Čito) community in northeast Neshoba County; they spoke mostly Choctaw. Getting re-immersed in the language was, as they say, just like riding a bike. The knowledge of the language was still there, deep in the psyche in my mind. I just had to bring it forward.

For Native communities, the death of an elder is so much more than losing a loved one. Often, in our pockets of culture throughout these United States, one can find a common theme no matter where the tribe or culture is located from coast to coast: each loss of an elder means more depletion of cultural wisdom and collective knowledge of a tribe. Some tribes aren’t so lucky to have an aging population, so with each death, it is a substantially bigger cost to the culture with each passing than other tribes with larger populations.

Repairing the ‘Broken Foot’

For many Choctaws, wills and testaments aren’t a common thing. Some families may be fortunate to know the wishes of their grandparents ahead of time, but just as our ancestors did many moons ago, any instructions were passed down orally rather than written in a formal, legal document.

To me, the lack of a formal document detailing the last wishes of any family member hadn’t posed too much of a problem in general; after all, we have been historically an impoverished people for many generations and have very little in possession, let alone land and property, to pass down to the next generation.

We take pride, instead, in passing down traditions, language and cultural knowledge we value more than “things.” This custom has changed more recently, as there may now be some cherished heirlooms, such as beadwork, basketry or whatever art form the person the deceased embraced, and the need to name the recipient of those items.

Still, the tragic passing of a family member in our communities follows a familiar pattern we all know well: The local funeral home is contracted to provide services for tribal members, and a social worker is assigned as a liaison between the funeral home and a designated member of the family acting as a spokesperson. A meeting is set up in an office, and the funeral director collects information for the obituary. The liaison takes over and irons out details for the funeral service and the wake.

Typically for most Choctaw families, the wake is a 24-hour event and takes place at the home of the deceased or a relative. For some families, like mine, these marathon wakes are at the church if the tribal member was an attendee, often displacing the mid-week service, if need be.

Choctaw tradition also has it that a person or persons should be designated as the firekeeper through the wake, and these fires provide the heat for the outdoor preparation of the three meals per day provided for the wake and the final meal immediately following the funeral services. The chosen cooks go grocery shopping with funds the social-services office provides, and the dishes usually include frybread, Choctaw hominy, fried chicken, and a variety of vegetables like okra and black-eyed peas. If the cooks knew how to make it, sometimes banaha is served, which is a dish best described to outsiders as similar to a Mexican tamale.

The collective nature of Choctaw funerals stems from the old custom of what was called “iyyi kowa,” literally translated as “broken foot.” Generations ago, if a Choctaw family suffered a setback, such as a death in the family, the community would come together and gather what was needed to help the family in their time of need.

We are still that tribe of close bonds and continue to practice today what our ancestors used to do, especially in that period between 1830 and 1945 when we had no formal government representing us. Choctaws weren’t even considered “citizens” in Mississippi then despite the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830 allowing for citizenship (which was only haphazardly done, if at all) and finally, in 1924, in this state of Mississippi that Europeans built on our land.

Firekeepers: Now 6 Feet From Each Other

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected countries and cultures all over the globe, interrupting the way of life for everyone, and it is no different here on the Choctaw Indian Reservation in east-central Mississippi. The general public sees the closure of the tribally owned Pearl River Resort casinos, affecting Choctaw and non-Choctaw employees alike—who, by the way, live in surrounding Mississippi counties, even those with no reservation land.

After the COVID-19 outbreak, the Office of Public Health Services at the Choctaw Health Center issued a guidance document detailing how to safely proceed with funerals and wakes in these days of social distancing and in accordance with CDC recommendations and keeping in mind the reverent customs of the Choctaw funeral.

The guidance now suggests that services are done outside by the gravesite with no wake—meaning no meals—or final viewing and strongly suggests, rightly so, no shaking of hands and hugging of the mourning family. The traditional final meal after the funeral should not occur or be limited to immediate family only. Because our funerals are typically a community-wide event, especially for an elder, it needs to be limited to immediate family only and with a memorial service postponed to a later date when hopefully, the overbearing threat of this virus has moved on.

For Choctaws, this may be the hardest part of the public-health guidance to follow—to be told not to attend services or to be able to provide physical comfort for the family in mourning.

Thankfully, there are some things the coronavirus cannot change. Just as we Choctaws have done for so long with the Iyyi Kowa tradition and coming together to provide for the family in their time of sorrow, and so long as the firekeepers keep 6 feet from each other, they can safely watch over the glowing fire that burns throughout the night in solidarity of keeping our tradition alive in these unprecedented, uncertain times.

[photo credit: map via WikiCommons]

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,000 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.