NOXUBEE COUNTY, Miss.—On a hill in an area of Macon, Miss., that locals call “Depot” lies the remnants of Central Academy. Today, the facilities that opened in 1968 to defy school integration look a bit like the inhabitants were raptured. A jacket lies on empty bookcases stacked on their sides behind the glass doors of the John L. Barrett Elementary School. In the back, construction-paper cutouts circle a blackboard. A maroon office chair sits dusty near the entrance.

The windows of a yellow school bus backed up into the treeline are busted out. Likewise, overgrown trees and bushes obscure much of the large triangular white entryway to the high school with a big blue CA in the middle. Old sponsorship signs, like Macon Stockyard, still hang on the fence of the football field. The dilapidated dirty-white buildings dotting the 16-acre complex appear as though the previous occupants simply got up one day and walked away.

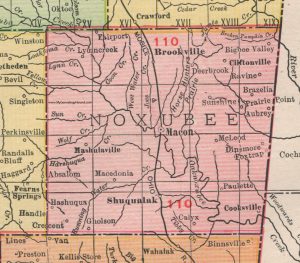

White parents chartered the nonprofit Noxubee Educational Foundation Inc. on Sept. 17, 1964—just 17 days after the FBI found the bodies of three civil rights and Black education activists in nearby Neshoba County and as the U.S. Supreme Court inched closer to forcing southern schools to finally heed 1954’s Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision and integrate.

Businessman Arthur Varner, then the owner of Macon Oil Company and Noxubee Tire Service, built the white private school for a bargain $3 a foot, CA’s now-defunct website explained. The Macon High School and Mississippi State University graduate attended Macon Presbyterian Church with John L. Barrett, who news accounts show resigned as superintendent of Noxubee County Schools in July 1968 and became headmaster of CA within days to help open it on Aug. 1, 1968.

Barrett was also a public-school product. He graduated from Shuqualak High School, south of Macon, and the University of Mississippi where he played football. As an educator, he had also been principal of Macon High School. He was active in white, conservative politics, which was then centered in the staunchly segregationist Democratic Party before an eventual party switch on race issues as the modern Republican Party started using the southern strategy to attract frustrated southern white Democrats.

His wife, Ann Ford Barrett, was Miss Macon High School and later a teacher at the still-segregated Macon Attendance Center before joining her husband to run Central Academy until they retired in 2007. She taught American and Mississippi history at CA, as well as reading. When she died in 2016, her family included Central Academy as one of the beneficiaries of gifts in lieu of flowers.

Central Academy was one of Mississippi’s dozens of segregation academies that opened in the 1960s in anticipation of a final Supreme Court mandate, while many others were “founded in 1970” soon after the Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education decision finally ended legal public-school segregation. White leaders in the always-majority-Black county with long-embedded inequities for its descendants of slavery demanded and often got public funding even as they excluded Black children and openly taught racism to many of today’s prominent white Mississippians and decision-makers.

State Pay-Offs to Form Segregation Academies

Beatrice Alexander, a Black mother in Holmes County in the Mississippi Delta, was the woman who ultimately beat laws backing up segregated schools. She had sued the Delta school district for making no “meaningful” effort to integrate public schools and finally offer a truly equal education to Black children. She won her case when the U.S. Supreme Court told 30 Mississippi school districts to integrate by Feb. 1, 1970, with other southern district holdouts to follow suit.

White Noxubee County leaders were ready for that decision, however. They had refused since 1954 to give Supreme Court-mandated school desegregation efforts more than a wink and a nod. At the same time, white federal district judges in states like Mississippi sent mixed messages at best. Charles C. Bolton wrote in “The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980” that the state and its school districts made efforts in the “freedom of choice” years of 1964 to 1968 to invest more into Black public schools than they ever had in order to stave off full desegregation.

Until then, white Mississippi had intentionally starved Black public schools out of resources with inadequate or crumbling facilities with no plan to change it. In the shadow of the Brown decision, the Noxubee County School District and others started consolidating tiny Black schools and allocating more resources and building investment for what they still called “Negro schools,” Bolton wrote.

One Mississippi-based judge even ruled in 1966 in writing that Noxubee districts had to “abolish” separate schools, while threatening white district officials verbally that he would transfer 400 Black students into the white schools if white district officials didn’t improve the remaining schools. The idea was to buy themselves out of school integration.

Meantime, white State of Mississippi and Noxubee leaders were preparing for what they considered the worst outcome: forced integration. The same year Central Academy’s nonprofit formed, in 1964, the Mississippi Legislature passed a State-organized tuition-grant law to allow transfer of tax funds to white parents moving their kids to private segregated schools—what is today referred to as “school vouchers.”

That pay-off helped get early seg academies off the ground, including rural Leake Academy near Carthage and rabidly racist Citizen Council schools in Jackson, Bolton wrote. One of white Mississippi’s most urgent concerns was that mixed schools would lead to miscegenation, or race-mixing, with an inferior race, which would in turn destroy the supposedly superior white race.

Gov. Paul B. Johnson Jr. called the special session in 1964 that approved the early voucher law. He had run a virulently racist campaign the year before, repeating in his stump speeches that NAACP stood for “N—–s, Alligators, Apes, Coons and Possums.”

Academy founders like CA’s Barrett, who was also a leader in the Mississippi Private School Association that formed to support segregation academies, believed that money paid to send white kids to their own schools should be tax-deductible and that white families deserved tax dollars from the State of Mississippi to ensure their kids were educated in white-only schools.

Secret Services for the Seg Academy

Resistant white families continued well past 1970 to believe they were entitled to take public resources with them as they slammed public-school doors behind them. Central Academy, in fact, did battle with the federal government and civil-rights activists throughout much of its tenure over its practices to remain segregated and nonprofit. The IRS revoked CA’s tax-exempt status in 1971 due to its refusal to admit Black children, but it kept trying to suck in public resources.

By 1978, the Mississippi attorney general’s office had to force four academies—Manchester Academy in Yazoo City, Washington Academy in Greenville, Pillow Academy in Greenwood and Noxubee’s Central Academy—to repay $50,000 in public funds misallocated to the whites-only schools.

In 1982, when President Ronald Reagan disagreed with the one Democratic and two Republican presidents before him and tried to make segregation academies tax-exempt again, the IRS included CA on a list of 111 private schools with revoked status due to racism in admissions. Dozens were in Mississippi including academies in nearby Starkville, Meridian and Columbus, and several in the capital city including Jackson Academy and Citizen Council schools. Bob Jones University in South Carolina was also on the list.

Reagan would eventually withdraw support for the re-exemption after the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law in Mississippi obtained an injunction to stop it.

A Little Help from White School Board Members

One ongoing Central Academy problem for the county’s public schools was that the seg academy’s connections to white Noxubee County school-board members helped it draw resources directly from the public-school district. In 1982, Morris Kinsey of the NAACP and state Rep. Tyrone Ellis of Starkville demanded that all Noxubee County board members with knowledge of the secret help for CA to resign.

After all, it wasn’t like the white power structure of school boards disappeared when Beatrice Alexander won her Supreme Court case in late 1969. With school-board members elected, many boards remained under white control through the 1970s with Black candidates meeting a wall of resistance from white voters, Charles Bolton explained in his book.

In 1975, Black Noxubee County school music teacher Reecy Dickson decided to run for the school board saying the white members “didn’t really care” how Black children were educated. She ran pregnant as an independent candidate, helping new Black voters register, Bolton wrote. She was threatened, her car vandalized, and her opponent painted her as a crazy woman. The white county attorney also visited Black homes hinting at voter irregularities, and white people harassed Black voters at the polls with insults like “you can’t read,” Bolton recounted.

Dickson lost. The district then tried to fire her, but she later ran for superintendent in 1979 and won, prompting the all-white superintendent’s staff to quit. She was the first Black person elected to a county-wide office in Noxubee in the 20th century, despite its historic Black majority, but the majority-white board resisted Dickson’s requests.

By the time she left office in 1984, four of the total five school-board members were Black, Bolton wrote—which finally made it harder for the board to slip taxpayer-funded freebies to Central Academy.

What Central Academy Children Learned

By the time Central Academy closed in 2017 due to costs and withering enrollment, it had followed suit of other schools founded to segregate white kids and was admitting a small number of Black children, usually in low single-digit percentages, still a trend today in most schools that opened to only admit white kids. Like so many others, CA had rebranded itself fully by then as a “Christian academy,” promising high-level college prep with its slogan “Unlocking and expanding God’s great gift—the mind.”

CA’s website stated in 2016 that it used the Abeka and Bob Jones curricula—fundamentalist Christian textbooks and lesson plans that helped grow multi-million-dollar companies as families left public schools and fled to religious and segregation academies starting in the 1960s and 1970s. Both Abeka and Bob Jones teaching materials are based on core conservative religious and political beliefs that often run counter to both science and the critical thinking needed to succeed on the college level and, especially, to understand efforts at racial justice through the Civil Rights Movement or today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

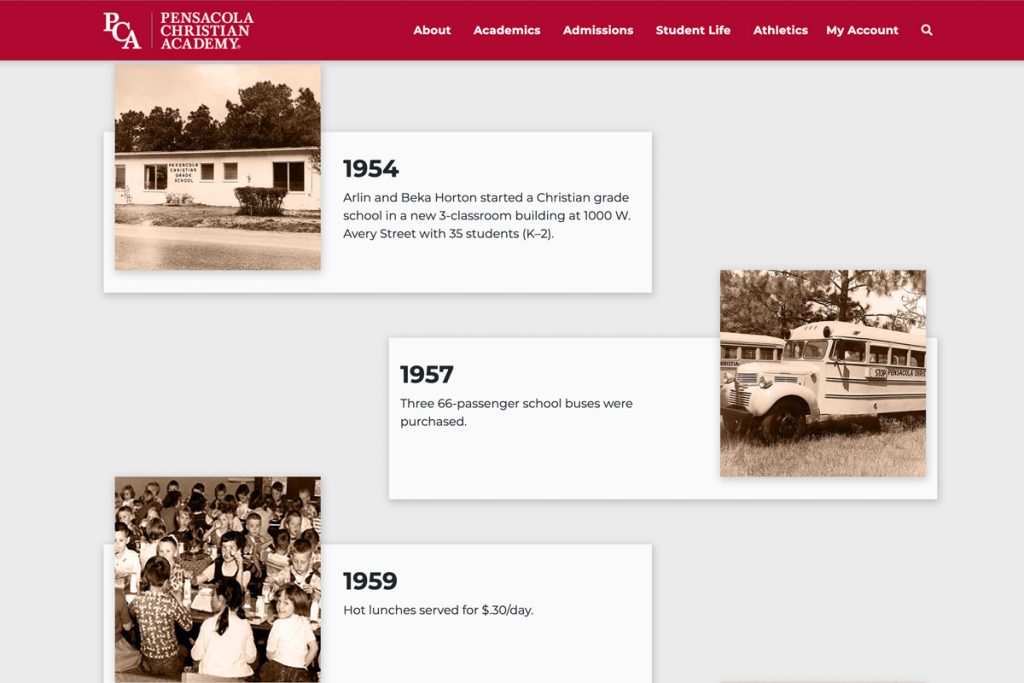

Abeka founders Arlin and Rebekah Horton had met when they attended Bob Jones University in Greenville, S.C. Bob Jones Sr., a segregationist who said it was God’s idea, founded BJU in 1927 during the Scopes controversy to, in part, resist teaching the science of evolution. Long after its namesake, and de jure school segregation, died in the 1960s, the college drew national attention in 2000 for its ban on interracial dating after George W. Bush made a stop at the college during his presidential campaign.

Christianity Today reported then that BJU had refused to admit Black students starting in the 1950s until the 1970s, justifying its racist bans “by saying that God created people differently for a reason.” Like myriad seg academies, BJU lost its tax-exempt status in 1983 due to its segregationist policies.

After their bond formed at Bob Jones, the Hortons later founded a small private school, Pensacola Christian Academy, in Florida in 1954—incidentally the same year as the Brown v. Board decision. From there, the couple developed its popular K-12 curriculum that has guided the education of generations of children for nearly 70 years. The Bob Jones curriculum came after forced school integration.

“In the early 1970s, the Lord impressed two Bob Jones University science professors” to write its first textbooks, the BJU website explains. In 1978, BJU released a book that its website says “established a scriptural defense of the Christian school movement.”

The Orlando Sentinel reported on Abeka’s finances, as well as its political and revisionist curricula, in 2018: “Today, Abeka Academy Inc. takes in $45.6 million in revenue—$6 million less than its reported expenses of $51 million—according to the nonprofit’s tax documents for the financial year that ended May 2017.” The Sentinel reported that private schools that use the Abeka and similar curricula also participate in that state’s $1-billion voucher strategy to pay for low-income students with special needs to attend private academies, which often can afford services public schools cannot.

Central Academy’s curricula went far beyond teaching basics of Christianity; it pushed the kind of conservative economics and politics that routinely calls for the rejection of government assistance. It is a political philosophy that tends to blame and disparage those living in deeply entrenched poverty in a county like Noxubee with its long history of racism, white terrorism and intentional practices that blocked Black children from education and resources equal to that white students enjoyed often with government help.

Even in first-grade history lessons, Abeka teaches “the benefits of free-enterprise economics … in contrast with the dangers of Communism, socialism and liberalism”—what the Washington Post called a “gospel of wealth.” In at least some versions, its 11th-grade history text is dismissive about the effects of poverty on communities saying that a “lack of homeowner’s pride” helps lead to “vandalized and neglected housing,” when the realities are far more complicated.

Minimizing Realities of Slavery, Confederacy

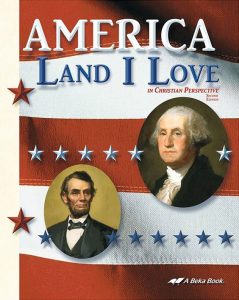

Both Abeka and Bob Jones curricula contain lessons downplaying the harms and realities of slavery, blaming the nation’s first Black president for worsening race relations, dismissing the Black Lives Matter movement as harmful to America and romanticizing the Confederacy. In their versions that have reached millions of students since 1972, white Americans have done little wrong throughout history.

In fact, Abeka’s 11th-grade history text pushes the white-supremacist myth that the Ku Klux Klan was a secret society meant to improve southern lives during Reconstruction and only sometimes “resorted to violence”—rather than a more accurate telling of KKK terrorism captured in public and government documents, as Michael Newton details in his county-level book on the KKK in Mississippi.

It certainly doesn’t teach that the KKK, started by Confederate offices and planters, and its myriad progenitor and copycat groups used force and threats in its mission to burn and terrorize Noxubee’s early Black schools. Nor that the KKK brutalized Black educators in the county to prevent the education of advancement of the majority of the county’s children.

Abeka’s textbook “America: Land I Love In Christian Perspective” shared a popular white myth about Black people during Jim Crow segregation and the Civil Rights Movement: “Most black and white Southerners had long lived together in harmony; they had been taught to accept segregation as a way of life,” it states as if it was fact that Black people enjoyed complete white control over their lives, choices, education and opportunities. The same textbook has declared: “Through the Negro spiritual, the slaves developed the patience to wait on the Lord and discovered that the truest freedom is from the bondage of sin.”

The 2005 edition of the same book honors a prominent slave owner and Confederate leader with a full-page tribute called “Robert E. Lee: The Great Christian General.” The text avoided Lee’s less-than-Christian approach to slavery and his documented abuse of enslaved Black people, but pointed out that he loved the Bible—representative examples of revisionist lessons that earned the Abeka text horrified reviews on Amazon.

Mennonites: ‘Evangelization by Colonization‘

Central Academy wasn’t the only private school that emerged in the wake of forced integration that drew white kids out of the Noxubee County schools.

Six years after the Brown v. Topeka (Kansas) Board of Education decision, six Mennonite families moved from the Midwest to the sweeping flatlands of northeastern Noxubee County, including out toward Prairie Point, the site of many plantations with enslaved Black workers when the Civil War began. Most of the early planters’ families eventually moved on once free Black labor was no longer available, and the area was overwhelmingly Black when the Mennonites showed up and started buying the remnants of earlier plantations.

The first families, members of the Conservative Mennonite Conference in Indiana and descended from Anabaptist traditions, had come south in 1960 looking for fertile soil for farming and to establish a new outpost for their “evangelization by colonization” strategy, as religion historian David R. Swartz wrote for Mennonite Quarterly Review in 2014.

In Noxubee County’s northeast precinct, the white Mennonite families started buying up decaying plantations in an area where 3,360 Black people and 329 whites lived in 1960, but with no Black people in the county registered to vote. In so doing, Swartz wrote, many Black families lost land where they hunted and fished as had the Choctaws before them in the county—for both communities, a vital part of keeping their families fed.

The religious pioneers also established the Magnolia Conservative Mennonite Church as the center of their new community, initially sending their children to still-segregated public schools. Swartz writes that the Mennonites were caught in the middle of Mississippi’s race wars. By faith, they were more “sensitive toward blacks than their white neighbors,” he writes, and more likely to associate across race lines. But white people were in total control; the banks wanted to loan money to the religious immigrants; and the local economy needed Mennonite money and job creation.

Noxubee County was bleeding population when Mennonites started buying up land—it would fall from 25,669 people in 1940 to 14,236 by 1970, dropping by half in the northeast precinct where the Mennonites chose to resettle, replacing many farm jobs with mechanization.

When the Mennonites arrived, local whites had a code in place in Noxubee County to keep Black wages low and inequity embedded: no livable wages. They, thus, pressured the Mennonites not to follow their instincts to raise wages for Black field workers they might hire to more than $2 a day, thus helping keep Black earning potential suppressed even as white supremacists pointed to cycles of Black poverty as evidence of inferiority and laziness—still a myth for many Americans today.

Swartz reported that the median income for nonwhite farm workers in Noxubee County was $714 a year then with the median income for white people four times as much.

White Noxubee County residents had demanded wage and economic suppression for Black people since losing the Civil War and the right to free labor, as well as violently targeting Black schools and educators for decades to stop advancement. A major goal of the early KKK and similar violent groups in Noxubee County was to economically subjugate Black people so that “the majority of the white citizens may control labor,” as Newton reported in his book on the Mississippi KKK. The terrorists’ response was to target both Black and white people who violated their plan to keep American descendants of slavery mired in poverty.

Mennonite Success on Former Choctaw Lands

Steeped in historic irony, the agrarian Mennonites did well farming former Choctaw lands with many over time coming to Noxubee County from west of the Mississippi River, including Oklahoma and Kansas. They, like earlier white planters decades before them, thrived on fertile acreage ceded in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek signed in Mashulaville in Noxubee County over a century after most tribal members left their homeland and trudged the “Trail of Tears and Death” as one Choctaw chief called it, to those very states Mennonites were leaving.

Mennonites also settled in Mashulaville near the treaty site and other Mississippi counties in the early 1960s, opening the Mashulaville Mississippi, a Choctaw Indian mission, to minister to the remaining Choctaw community there.

“The first 12 to 15 years were fairly prosperous for our people,” Mennonite Galen Nichols told The Clarion-Ledger in 1985. “Farming has been good to us.”

By their faith’s dictates, religion historian Swartz writes, Mennonites are separatist, protectionist, non-confrontational and refuse to vote or run for office, which meant that, as a community, many were reluctant to stand up for Black equality for their new Noxubee County neighbors as the Civil Rights Movement swirled around them.

But there were exceptions. Mennonite Larry Miller moved south from Indiana and became active in the Civil Rights Movement, he says on his page on the Civil Rights Movement Veterans website. “I helped people register to vote, took them to doctors, worked at a Native American church mission, and was in and out of trouble for reasons that I cared about the poor people around me,” Miller wrote.

“I remember the day that Martin Luther King was killed. Black people were weeping tears of sorrow, and white people were jubilant. It was and often still is, this seedbed of racism and selfishness that I and my family have had experiences in Noxubee County. I married my childhood girlfriend, went to college in the south and own a farm now in Macon, Mississippi. I am a teacher in public schools and am active (in) lots of community development activities.”

But as a general rule, Mennonite immigrants into Mississippi were both socialized and intimidated into adapting to the white segregated culture, historian Swartz found.

That was never more apparent to Black people in Noxubee County than after the 1970 Supreme Court decision ending segregated public schools.

Following the White Flight of 1970

Within months of the early 1970 Alexander v. Holmes decision meant to finally end segregated education, the Noxubee Mennonites pulled their kids out of public schools and launched their own private institutions. That included Magnolia Mennonite School between Macon and Brooksville (now called Magnolia Christian School since the 1990s) and South Haven Mennonite School about 10 miles from Magnolia east of Macon near Prairie Point.

“Conviction arose within the hearts of our brethren for the need of our own school, where Bible doctrine and principles could be included in their educational curriculum,” Swartz quoted local Mennonites saying. But he wasn’t completely buying it.

“That such a conviction coincided so directly with the desegregation of the public schools was, at the very least, unfortunate,” Swartz wrote. He added that the Mennonite departure left only two white members of the senior class at Noxubee County High School in Macon with the pubilc-school system then more segregated than before the Supreme Court stepped in.

In 1974, the Delta Democrat-Times reported, the South Haven Mennonite School was included with three openly racist segregation academies—Sylva Bay Academy in Bay Springs; West Tallahatchie Academy at Tutwiler and Country Day School at Marks, Miss.—in a federal court ruling that they were ineligible for the state-funded textbooks they were already using.

The reason? The four fully white schools had racially discriminatory admissions policies, U.S. District Judge William C. Keady ruled. It was three years after the IRS had revoked Central Academy’s tax-exempt status for the same reason.

Today’s Noxubee County Mennonites welcome Black students into their majority-white schools and work with local Black and Native Americans in mission work. But Noxubee County schools are nearly as segregated as they’ve ever been. Even after Central Academy closed in 2017, white kids remaining in Noxubee County did not rejoin the public schools.

“Instead of those kids coming here, they went on to Kemper Academy,” Noxubee County High School principal Aiesha Brooks told the Mississippi Free Press about another historic seg academy in the next county south of Noxubee. “Believe it or not, we still have teachers here who still send their kids to the academies.”

Today, the now-consolidated Noxubee County School District serves all public-school students in the full county in its facilities in Macon with all other local public schools closed. Now under State of Mississippi takeover, the Noxubee district is over 97% Black, 1% white, 1% Hispanic and 1% two or more races. As of the 2020 Census, Noxubee County is 69.9% Black, 25.6% white and 2.4% two or more races.

Torsheta Jackson contributed to this report.

This in-depth Noxubee County historic report is part of the “(In)Equity and Resilience, Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” project looking at systemic inequities long facing Mississippi’s Black women and their families and institutions that the pandemic revealed and exacerbated in Mississippi. In upcoming weeks and months, the BWC Project team is publishing what their systemic reporting and numerous solution circles with Black women revealed about three counties (so far): Noxubee (education); Hinds (violence and public safety) and Holmes (health care adequacy and access). The journalists are following up each county overview with specific solutions-journalisms pieces about problems their reporting revealed.

Also see: Jackson Advocate Publisher DeAnna Tisdale’s opening column introducing the BWC Project and Torsheta Jackson’s overview of systemic inequities in her native Noxubee County. Visit the full BWC Project microsite here.

This project is a collaboration between the Mississippi Free Press and the Jackson Advocate with support from the Solutions Journalism Network. Read first-hand accounts from former students at segregation academies here.

Write solutions@mississippifreepress.org to offer feedback on the reporting or reach out to Kimberly Griffin at kimberly@mississippifreepress.org if you’d like to sponsor work in additional counties for this project.