A new federal voting-rights bill would not overturn Mississippi’s voter ID requirement for voting, despite claims U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith repeated yesterday as she denounced S. 1, the “For The People Act,” casting it as a “radical” intrusion on state’s powers.

“The legislation before us today would nullify Mississippi’s successful voter ID law. Under S.1, in a federal election, an individual could walk into a polling place, register and vote on the spot, without ever showing any proof of identity or residency,” the Republican senator said in a statement.

Supporters say their goal with the bill is to make voting easier and to curtail state efforts to enact new voting restrictions.

Though the legislation would require all states to offer same-day voter registration, as 21 states already do, it would not undo state voter ID laws. Even so, the bill’s text says voter ID requirements can have discriminatory effects on the poor and communities of color, though researchers have reported mixed findings. Some states, the text says, have “voter identification laws that discriminate against Native Americans” because they do not recognize tribal IDs for voting.

Mississippi Already Meets Most Requirements

The For The People Act requires states with voter ID laws to allow would-be voters who do not have photo ID when they arrive at the polls to satisfy the requirement “by presenting the appropriate State or local election official with a sworn written statement, signed by the individual under penalty of perjury, attesting to the individual’s identity and attesting that the individual is eligible to vote in the election.”

The For The People Act also bars states from requiring voters who cast ballots by mail to include photo ID.

Those changes would have little impact on Mississippi’s voter ID law, though. Mississippi voters can already vote by sworn affidavit if they do not have a photo ID on Election Day, and their ballot will count so long as they present an accepted form of ID to their circuit clerk’s office within five business days.

In some cases, Mississippi already allows blanket exemptions to the voter ID requirement. Voters who have religious objections to being photographed, for example, can vote if they sign a sworn affidavit. Though Mississippi does not have universal mail voting like many states, those who do vote by mail are also exempt from photo ID requirements, including those who vote absentee by mail, uniformed military officers and overseas voters (the latter two groups may also vote by fax or email without including ID).

And unlike some states with photo-identification requirements for voting, Mississippi accepts tribal IDs for voting and requires local circuit clerks to provide free voter identification cards to those who need them.

Hyde-Smith Shares Voter Impersonation Story

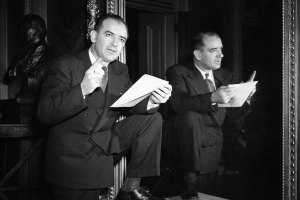

Fellow GOP senators flanked Sen. Hyde-Smith in the U.S. Capitol yesterday as she explained her opposition to the For The People Act. The Brookhaven native shared a hometown story to bolster her claim that voter fraud is a serious issue that photo ID is needed to address.

“I’ve been sitting in a committee hearing (where other senators say) how there’s not significant voter fraud. Let me tell you about Jennifer Jackson in Brookhaven, Mississippi—my friend, she’s a friend of Senator Romney’s as well. She called and said, ‘Cindy, I went to vote, they told me I had already voted,’” Hyde-Smith recounted. “Then, she looked above who signed her name, and her deceased father had already voted that day, too. So don’t tell me there is not voter fraud.”

Sen. Hyde-Smith’s office did not respond to a request for additional information on that claim yesterday, but the Mississippi Free Press tracked down a Jennifer Jackson in Lincoln County who said she is the friend Hyde-Smith was referencing.

The incident happened decades ago, though, Jackson said, several years after the 1993 death of her father, Don Jackson. She had recently moved, but the voter rolls had not been updated to reflect her change of address, which meant she had to cast her ballot at the Lincoln County courthouse.

“They weren’t going to let me vote, and I pitched a fit because they said, ‘You’ve already come in and voted and signed your name here,’” she said. “And I said, ‘No, it’s not, that’s not me.’ … So I really had to insist that they let me vote, and I had to fill out an affidavit ballot. And after I filled out all of that, I was suspicious, so I looked at my dead dad’s name, and he had voted, too.”

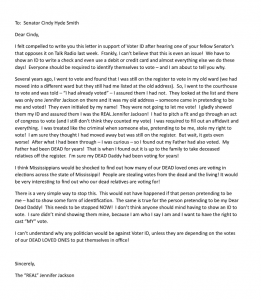

Jackson shared a March 2010 letter she wrote and sent to Hyde-Smith, who was then a Democratic state senator in the Mississippi Legislature. In the letter, Jackson recounted the voting incident as she argued in favor of requiring voters to show a photo ID at the polls, saying that “everyone should be required to identify themselves to vote.” She signed the letter, “The ‘REAL’ Jennifer Jackson.”

The Mississippi Free Press is unable to verify Jackson’s story about the voter rolls, however, because the rolls themselves no longer exist. Lincoln County Circuit Clerk Dustin Bairfield said in an interview today that the county only keeps those records for 22 months in accordance with federal and state laws.

Bairfield, who became circuit clerk in 2012 after working for the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Department since the late 1990s, said he is not familiar with Jackson’s story. He said he is not aware of any instances in which someone fraudulently voted under another person’s identity or on behalf of a deceased person in Lincoln County. A 2014 Washington Post report found just 31 credible claims of voter impersonation out of more than 1 billion votes cast from 2000 to 2014.

In some cases, poll workers or voters make mistakes, such as initialing beside the wrong name when another voter has a similar or identical name, Bairfield told the Mississippi Free Press. He trains his poll workers to point to the exact line voters need to initial, he said. The circuit clerk also said he thinks voter ID and including date of birth on voting rolls can help avoid some of those pitfalls.

“It may be a poll worker’s error, but that’s not what the person standing there is going to think,” Bairfield said, adding that voter ID requirements are “not here to stop anybody from voting” but “to make sure any legal vote is counted and any illegal vote is not counted.”

At least one other longtime Lincoln County resident’s maiden name is identical to Jennifer Jackson’s, but the one Hyde-Smith referenced said she does not believe the incident resulted from a mix-up.

“I was the only Jennifer Jackson on the roll. … They (let me vote affidavit) to appease me back then. I was treated like I was the one who had done something wrong,” she said.

Brookhaven Reporter Regrets Writing Story

Three days after Jackson sent her letter to Hyde-Smith, on March 13, 2010, The Daily Leader in Brookhaven published a story on the allegations titled, “Victim of Voter Fraud Hoping for ID Ballot Passage.” It quoted the then-state senator, who was already a supporter of creating a photo ID requirement for voting.

“Jennifer’s story is just an example that voter fraud exists—it’s alive and well. … I think voter ID will clean up a lot of elections,” Hyde-Smith said. Mississippi voters adopted a voter ID law the next year in 2011.

In 2019, though, two researchers from the University of Bologna and Harvard Business School who studied states with voter ID laws found that the requirements do not decrease voter turnout—but also do not decrease voter fraud.

“Using a difference-in-differences design on a 1.6-billion-observations panel dataset, 2008–2018, we find that the laws have no negative effect on registration or turnout, overall or for any group defined by race, gender, age, or party affiliation. … Finally, strict ID requirements have no effect on fraud – actual or perceived. Overall, our findings suggest that efforts to improve elections may be better directed at other reforms,” wrote researchers Enrico Cantoni and Vincent Pons.

After Hyde-Smith shared Jackson’s story anew yesterday, the author of the March 2010 Daily Leader story, Adam Northam, tweeted that he regretted writing it.

“For years I’ve been embarrassed I wrote it. Our boss was big on Republican issues and set me on the story, so I wrote it up. And years later the story of one single dead guy in Lincoln County being marked as voted is held up like a heavenly truth about voter fraud. When in actuality it was probably just a mistake by a 90-year-old poll worker,” he wrote.

The Mississippi Free Press asked Northam if he had found any evidence that pointed to such human error when he was reporting the story. He said it was “pure speculation,” but that the idea that it was “some grand conspiracy by vote-stealing Democrats” made no sense to him.

“Why stop at Jennifer Jackson? Lots of poll workers in this area are elderly, and some of them were elderly a dozen years ago and still working the polls,” he said. “With a couple hundred people coming in over 12 hours, it could be easy to mishear or misidentify someone.”

But Jennifer Jackson told the Mississippi Free Press that she does not believe it was an accident and that if voter ID had been in place back then, it would not have happened. She said she does not know if election officials counted her affidavit ballot or not.

Jackson said that, as far as she knew, no one in Lincoln County ever investigated the incident. She said she did not report it to local law enforcement.

“I didn’t even think of that as an option. The people working at the polls couldn’t tell me who it was (that had signed the voter roll),” she said.

‘A Small Spread of Voter Fraud’

At yesterday’s press conference, Hyde-Smith said Jackson’s story motivates her to fight against the For The People Act even if the actual number of voter fraud incidents nationwide is miniscule.

“A small spread of voter fraud makes a difference. So I am totally against this. I will fight it every single day,” the senator said. “We need to have confidence that our vote counts—that there’s one person for one vote,” she said.

In her statement yesterday, Hyde-Smith complained that the bill would “force states to allow felons to vote in federal elections.” The For The People Act does require states to allow citizens convicted of crimes to vote “unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election.”

More than 200,000 Mississippians who have served their time are currently disenfranchised due to the state’s felony voter restrictions, which disproportionately impact Black Mississippians. The state first implemented those restrictions in 1890 as part of its broader Jim Crow efforts to target and disenfranchise Black voters.

The For The People Act makes other changes, too, such as requiring states to allocate voting resources “equitably” so that voters wait no more than 30 minutes in line to vote. During the November 2020 election, some voters in Mississippi stood in line for hours.

After the record-breaking turnout, Republican-led states introduced a raft of new voting bills that critics say will make voting more difficult, including in Mississippi.

Today, Republicans in Georgia adopted a sweeping new elections law that imposes voter ID requirements for absentee ballots, allows state leaders to take over local election boards and makes it a crime to give food or water to voters who are waiting in lines—some of them for as long as 10 hours. Data shows that non-white voters in Georgia, on average, spend significantly more time waiting in line to vote than white voters.

In Mississippi, though, all proposed bills to further tighten the state’s election laws have died since the legislative session began, including bills to make it easier to purge voters from the rolls and to implement proof of citizenship requirements.

“Luckily, many of them are dead at this point, but they can resurface at any time,” said Arekia Bennett, the executive director of Mississippi Votes. “It goes to show you that what happened in November when a record number of Mississippians, including Black or indigenous people who have been marginalized for centuries in this country, turned out to vote. … When this kind of thing happens, there’s almost always an attempt to turn us back to the Jim Crow era and package it as something else.”