As Americans watch the Electoral College process of choosing a president continue to play out, they may be unaware that voters in Mississippi just decided to get rid of a similar system in their state.

Like the national system of electors, the Mississippi system had its roots in both a racist election process and the desire to protect the needs of rural residents from being ignored or overruled by city dwellers.

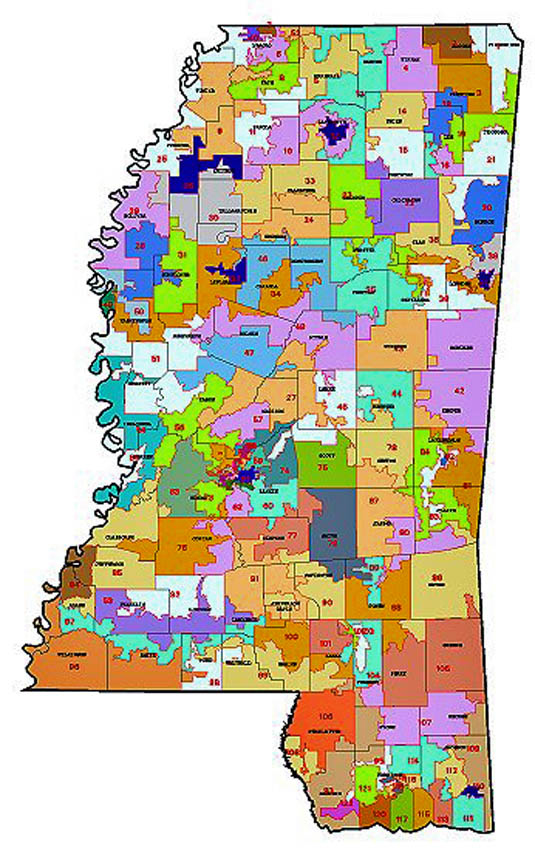

The state’s 1890 Constitution requires a candidate for statewide office to win not only the majority of the popular vote, but also a majority of the 122 state House districts. A candidate could win the statewide popular vote, but if they didn’t win the majority of the state House districts, the election would be decided by the state House of Representatives. Those representatives weren’t required to vote in accordance with the majority in their district.

This requirement has been cited as reducing the chances for nonwhite candidates to be elected to statewide office. In a state where 56% of the population is white—the rest are Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native or multiracial—66% of the House districts are majority white.

Rarely Used and Now Expired

The state House has made the decision only a small number of times, and just once at the level of the governor’s race. In 1999, then-Lt. Gov. Ronnie Musgrove, a Democrat, defeated Republican Mike Parker in a very tight contest. Musgrove won a plurality of the statewide popular vote, 49.6% to 48.5%.

But each candidate won 61 of the House districts, sending the decision to the state House of Representatives. At that time, Democrats held 84 seats, ensuring a majority. Two Republicans joined them to elect Musgrove by a margin of 86-36.

Twenty years later, as Election Day approached, the gubernatorial election was again considered close enough to potentially trigger this process. But ultimately, it didn’t happen: Republican Tate Reeves, then serving as lieutenant governor, beat then-state Attorney General Jim Hood, a Democrat, 52% to 46%. Reeves also won 74 of the 122 state House districts.

However, in advance of that election, four Black Mississippi residents filed a lawsuit claiming the system violated their federal civil rights. The Mississippi Legislature responded by asking voters whether this Jim Crow-era process should still exist.

Changing the Rules

In the November 2020 election, Mississippi voters decided to end that process and replace it with the requirement that a candidate get a majority of the votes cast or face a runoff election if nobody gets more than 50% of the vote. In other states, this process has its own racist history as a way to limit Blacks’ political power.

Supported by more than 78% of the state’s voters during an election with record turnout, the change formally took effect this month.

The people of Mississippi and their elected officials have sent a clear message that for statewide elections, they prefer the popular vote over a system like the Electoral College.

This piece was published in cooperation with The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit publisher of commentary and analysis, authored by academics on timely topics related to their research.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.