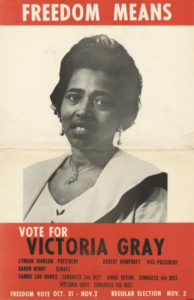

Victoria Gray challenged John C. Stennis for his U.S. Senate seat during Freedom Summer 1964, running as part of a party she helped found to challenge the then-all-white Democratic Party that opposed voting rights for Black Mississippians. Most white Mississippians saw this young woman as a modern Mississippi Don Quixote. Not only was she Black and a woman, but under state law she was also party to an illegal election.

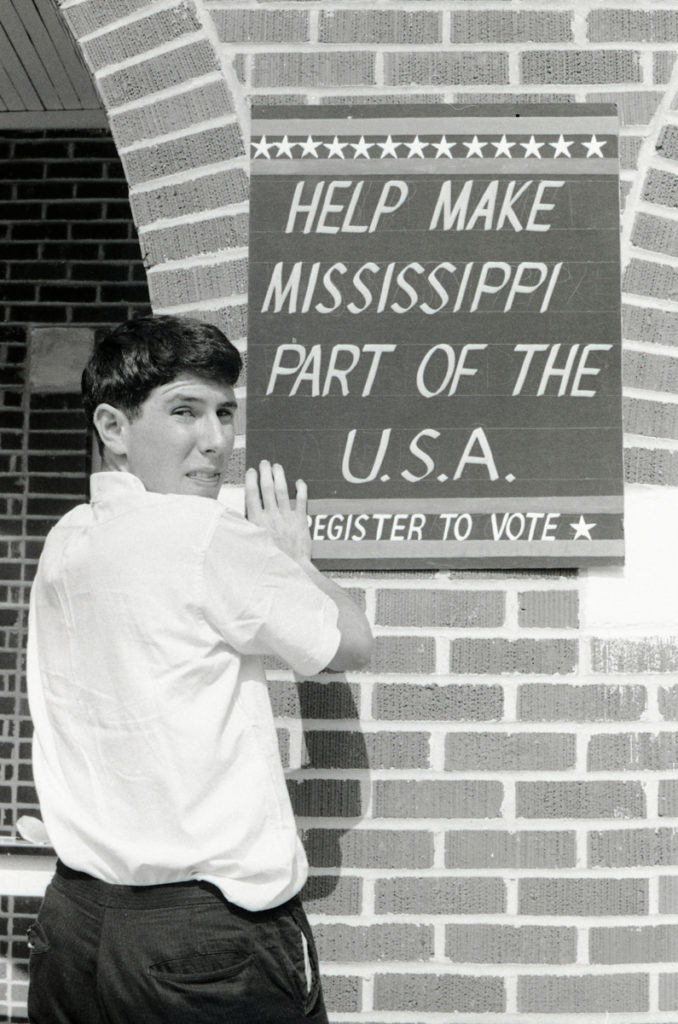

The press ridiculed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s primaries as “mock elections.” Yet the primary was very real for the Black people voting in it. When the November general election arrived, Mississippi refused to put any MDFP candidate on the ballot while church burnings, beatings and intimidation of black voters continued unabated. But Victoria Gray, who was from Palmer’s Crossing near Hattiesburg, refused to accept that Black participation in Mississippi politics was not possible. Her answer to Mississippi’s “Closed Society” was the “Congressional Challenge,” a dramatic but little-known slice of civil rights history that would shake white Mississippi to its core.

In 1997 I interviewed Victoria Gray Adams about these events. She was clear about the stakes, then and now:

Well the bottom line is: politics controls everything. Politics controls everything from the cradle to the grave. Before and beyond.

“Everything” to Victoria Gray was everything that matters. Education. Health and food for the family. A safe and good place for children to grow up. Everything the Declaration of Independence promised with its words “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Everything that white supremacy denied. She told me about her approach to politics:

I’m always looking at the possible. I’m able to recognize the improbability, but I am not willing to concede that on those bases that it’s not possible.

Victoria Gray became a field secretary for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1962. Soon she was one of the top leaders in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, helping create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge segregationist power. She also began working closely with two other women from different parts of Mississippi—Annie Devine of Canton and Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville. This is what Victoria Gray Adams told me about their collaboration:

It was an amazing partnership, I guess you would call it. And it was a marvelous experience… Mrs. Hamer was a natural orator. I mean, absolutely without peer. She was also a natural comedian, she brought a lot of humor and laughter. And at the same time could be as serious as anyone under the sun. Mrs. Devine was very—I called her the wisdom person. Quiet. But she always, always spoke with wisdom… My skill was in strategizing. And organizing. And facilitation.

Tom Dent, a noted Black poet and historian, once told me these women were the “big three” of the Mississippi Movement.

I asked Victoria Gray Adams about their most important accomplishment, and her answer surprised me. It wasn’t Freedom Summer, or the “Convention Challenge” of the MFDP that demanded seats at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. It wasn’t even voter registration per se:

I think that the Congressional Challenge did more to convince (white) Mississippi that people were just no longer going to tolerate the kind of walls that they had built around that state and that society. It was just not going to be acceptable anymore … the congressional challenge was probably the most impacting of the things that we did.

The Congressional Challenge was two things at once. It was a legal strategy, complete with a team of the nation’s top civil rights lawyers. And it was a public relations/political tactic aimed at the heart of Mississippi’s political power—its hold on the U.S. Congress.

The state had some of the most powerful senators and congressmen in the country. But while they might be immune from a challenge inside Mississippi, they still had to abide by congressional rules. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party prepared for the task by shifting candidates at the general election to face specific congressmen with Victoria Gray put up against Rep. William Colmer in the 5th District.

Aaron Henry replaced Gray in her run against Stennis, but the plan was to make a challenge only in the House of Representatives, where the Democratic Dixiecrats had less power. With their victories in the MFDP election, the women would demand the seats of the white representatives on the basis that Mississippi’s official election was fraudulent because it excluded Black people from the entire process.

Most outside the Movement saw the Congressional Challenge as a silly waste of time. Many inside the Movement saw it that way, too; they were discouraged after the failed challenge at the Democratic National Convention to seat a MFDP delegation instead of white segregationist Democrats.

The white congressmen who were the target of the challenge treated it like an insulting joke.

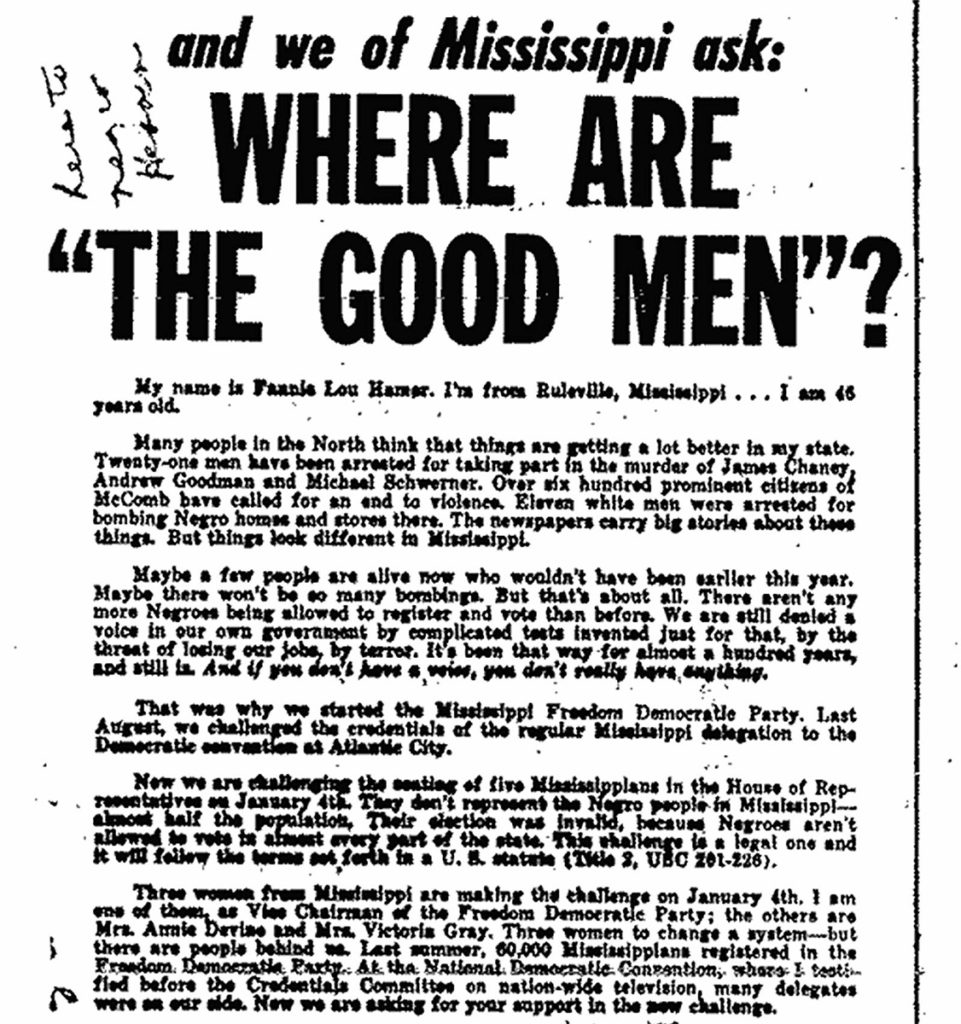

Just before Christmas 1964, the trio moved into a Washington, D.C., apartment to open a congressional office and make their case to the new Congress. Fannie Lou Hamer was the spokeswoman:

… we are challenging the seating of five Mississippians in the House of Representatives on January 4th. They don’t represent the Negro people in Mississippi—almost half the population. Their election was invalid, because Negroes aren’t allowed to vote in almost every part of the state. This challenge is a legal one and it will follow the terms set forth in a U.S. statute (Title 2, USC 201–226).

Three women from Mississippi are making the challenge on January 4th… Three women to change a system—but there are people behind us.

Hundreds and hundreds of Black Mississippians came to Washington for the opening of the new Congress and stood in silent vigil as representatives entered the House. The protesters held posters, each “speaking the sentiments of the person wearing it.” As Victoria Gray Adams explained:

I think you have to understand that there was an element here that was beyond the law. The rules, the regulations and all that sort of thing. I called it spirit. There’s an element of spirit involved here… one of the congressmen was heard to say (that) up until that morning, he had not really given any serious thought to the challenge whatsoever. But when he walked down that hallway and saw those people saying nothing but standing there, all of a sudden he realized the seriousness of this whole situation…

The mood became suddenly serious, clearly shaking the confidence of the white congressmen as Rep. James Roosevelt of California, the son of FDR himself, stood with the Mississippi women with words challenging white supremacists that thundered through the House chamber:

… they cannot run their society like Soviet Russia and then claim seats in the American Congress; they cannot win elections with a system based on murder and then claim the right to govern.

Roosevelt was supported by 147 fellow representatives. Only 70 votes more were needed to boot the white men and replace them with the Black women. Although the measure failed, a compromise put the Mississippi men on probation pending an investigation, their fate left hanging for nine long months.

For the first time since Reconstruction, White Mississippi began to put its legal house in order by 1965—hypocritically scrubbing State law of discriminatory voting rules, but without reforming any part of its informal system of voter suppression—it was too little, too late. The federal investigation of Mississippi politics produced thousands of pages of testimony by hundreds of Black Mississippians about abuses they had suffered while trying to register to vote.

These depositions paved the way for passage of the Voting Rights Act that August. On Sept. 19, 1965, Congress ruled that the Mississippi men could keep their seats—based in part on an assumption that the new voting law would end further political abuse.

Although the Congressional Challenge ultimately lost, 143 congressmen voted for the Black women that September, sending a clear message to Mississippi: don’t let this happen again.

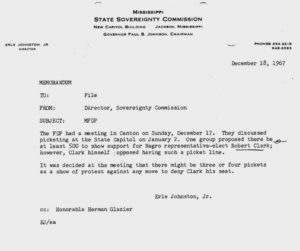

Two years later, Robert Clark of Ebenezer became the first Black official elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives since Reconstruction.

The Congressional Challenge wasn’t the end of struggle by any means. But it was the start of something new. It would be another five years before Mississippi public schools were finally integrated. Not until the mid-1970s would Black voters finally kill the old segregationist politics for good.

Real change finally arrived in 1979 when Black voters helped put the recently deceased William Winter in the Governor’s Mansion. Winter’s landmark education reforms were the result of hundreds of thousands of Black Mississippians demanding a new kind of politics—votes that came from years of struggle by Mississippi’s civil rights foot soldiers and leaders. These achievements owe a special debt to the little-known, but vastly important “Big Three”: Annie Devine, Victoria Gray Adams and Fannie Lou Hamer.

Many view civil rights as history, a period confined to the 1960s. But I’ve interviewed many activists from that time, and none of them saw it that way. For them the Movement has no beginning and will have no end. In 1997 I asked Victoria Gray Adams, “What do you think the future is between Black and white in America?” She paused at length, then said:

A continuing struggle on the part of those who want peace, with justice. And those who have no sense of either, or a desire for it.

The answer she gave then holds true for America today, even more so for Mississippi. Victoria Gray Adams left us a blueprint for that continuing struggle, one based in “spirit” and imbued with refusal to limit our hopes, just because something seems impossible.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.