RIDGELAND, Miss.—Steve Cunningham had expected to cast his ballot for this year’s presidential election at the same Madison County, Miss., precinct where he has voted since at least 2008: the Ridgeland Recreation Center.

Instead, the African American man is among about 2,550 mostly Black and Hispanic voters in southeast Ridgeland, a historic white-flight suburb just north of Jackson, who were quietly rezoned out of their racially mixed precinct this summer. They were placed, instead, into an already-majority non-white one.

Carol Mann, a Democratic candidate for District 1 election commissioner, told the Mississippi Free Press that the voters are being moved from a location “with adequate polling stations and adequate parking to an extremely cramped polling place” and that the change will cause “chaos and confusion.”

Though Cunningham received a letter in July informing him about the change, several residents in Madison County’s Supervisor District 1 told Mann and, later, the Mississippi Free Press, that they have not received notifications about the new location. They worry that the change is a racially motivated attempt to suppress the non-white votes.

Cunningham told the Mississippi Free Press on Wednesday that he believes “voter suppression” is the goal.

Non-white residents account for about 80%, or roughly 2,000, of the voters who have been moved from the Recreation Center to the apartments.

Packing Black, Hispanic Voters Into One Precinct

As recently as the March 2020 party primaries, the affected voters cast their ballots at the Ridgeland Recreation Center on Old Trace Park near the Ross Barnett Reservoir (named for the segregationist 1960s governor). Most voters in that precinct are white, but until the recent boundary change, it included a significant and growing non-white population that has helped make recent elections more competitive for Democrats—at least on the precinct level.

The change, which took effect quietly in July, means that around 2,470 mostly white voters will continue voting at the the Recreation Center, but 2,550 other voters, most of them Black or Hispanic residents who would have still voted there as early as this past spring, must now cast their ballots at The Mark Apartments precinct.

Even before the boundary shift, The Mark Apartments precinct was the only majority non-white polling place in the district and served 1,125 voters. With the boundary shift, though, it will now serve at least 3,670 voters. As a whole, the six precincts in District 1 serve just 1,932 voters on average.

The Recreation Center is larger with hundreds of parking spots, and officials expect it to have between eight and 10 voting machines on Election Day. The Mark, which will now serve about 1,100 more voters than the Recreation Center, only has 25 parking spaces available. As of this past weekend, election officials only expected to allocate about five voting machines to The Mark.

“I’m concerned there won’t be enough space to accommodate voters. I’m concerned about the motive behind it, the reasoning behind it,” Cunningham told the Mississippi Free Press on Wednesday.

While Republicans usually edge out Democrats in the Ridgeland Recreation Center precinct, Democrat Mike Espy won 1,288 votes in the 2018 U.S. Senate special election, compared to incumbent U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith’s 1,178 votes. Espy is on the ballot again this year, once again challenging Hyde-Smith for her Senate seat.

This year, hundreds more Democrats voted in the presidential primaries in the precinct than Republicans. After the boundary changes, though, the Recreation Center precinct will likely vote solidly Republican like all other District 1 precincts other than The Mark Apartments.

Mann, the Democratic candidate for election commissioner in District 1, told the Mississippi Free Press that she first realized something had changed when canvassing the district and making phone calls.

“We were calling to make sure people were registered to vote starting in September, and then I’d ask them where they went to vote, and they’d tell me the Recreation Center, but the secretary of state’s voter locator would say Mark Apartments. And I was scratching my head actually for a long while on this, and I thought the secretary of state voter locator must be wrong until one lady showed me a letter she had received,” Mann said Wednesday.

“And that’s when I went, ‘Oh, so they’re notifying people of the change.’ But as I went on, then I started asking people if they had received a letter, and then they would still say no.”

‘This is Going to Be a Big Hardship’

Mann said more than half of the voters she asked said they had not received a letter and were not aware that their polling location had changed. One woman, a 77-year-old, told Mann she was trying to rent a wheelchair so her husband could vote and withstand long lines. Mann informed the woman that she and her husband could vote in-person absentee at the circuit clerk’s office instead, though.

Many Mississippians have the option to vote absentee until 5 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 31, including people over 65 or with permanent or temporary disabilities. But unlike other states during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mississippi did not make early absentee voting universal, and many voters who are now in the Mark Apartments precinct, like others across the state, will have to vote in person on Election Day.

Mann said one woman whose voting precinct changed told her she planned to arrive at the Mark Apartments Precinct at 4:30 a.m.—even though the polls do not open until 7 a.m.

“This is going to be a big hardship for them, but they’re determined,” Mann told the Mississippi Free Press. “One lady said she was very ill, but she was going to stand in line all day. I’ve heard that from many people who say they know this was about voter suppression, but that they’re going to stand in line all day if they have to.”

One of the voters Mann contacted, T’knesha James, who is Black, told the Mississippi Free Press on Wednesday that she is among those voters who never received a letter notifying her about the polling-place change.

“When (Mann) told me, I didn’t believe her. I didn’t know who she was. And she was just asking if we planned to vote and if we were aware that our precinct had changed, and I said no, because we’ve always voted over on Old Trace Park,” James said.

“I’ve lived here for six years, and that’s where I’ve always voted, so I thought she was giving me misinformation at first, but then she gave me her card with her information on it and I saw she was running for election commissioner.”

James said she had never experienced “ridiculously long” lines at the Ridgeland Recreation Center precinct. Even though it served about 5,000 voters before the boundary change, she said there was always ample parking space and lines moved quickly.

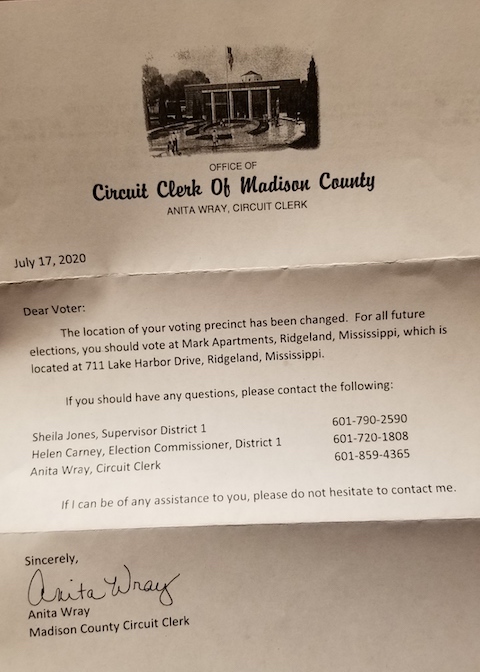

Mann shared a copy of the letter that some voters received from Madison County Circuit Clerk Anita Wray, a Republican, on July 17.

“The location of your voting precinct has changed. For all future elections, you should vote at Mark Apartments, Ridgeland, Mississippi, which is located at 711 Lake Harbor Drive, Ridgeland, Mississippi,” Wray wrote.

The letter only adds to the confusion for some voters, though, who, despite Wray’s claim that they would vote at the Mark Apartments for “all future elections,” received it along with a new voter registration card. The cards list their “County Precinct” as “The Mark Apartments Clubhouse,” but separately list a “City Precinct” as still being the “Ridgeland Recreation Center.” The voter card does not make it clear that voters must go to the Mark Apartments precinct for federal elections.

Wray’s letter informs voters that they can call her office or District 1 Election Commissioner Helen Carney, Mann’s opponent, if they “should have any questions.” The Mississippi Free Press tried repeatedly on Wednesday and today to call Wray’s office, but never got an answer or a call back. When this publication called Carney on Wednesday, she said that all inquiries about voting-precinct changes should go to Madison County Election Commission Board attorney Spence Flatgard.

Flatgard has not answered multiple calls since yesterday, nor an email earlier today.

‘This Is Being Done to Discourage Minorities From Voting’

Mann told the Mississippi Free Press that, when she spoke to Wray about the issue last week, the circuit clerk told her that representatives from the U.S. Department Justice had flown to Mississippi to meet her earlier this year and had “ordered” the change.

But the Department of Justice has not had oversight of precinct changes in Mississippi and other states with a history of racial discrimination since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a core part of the Voting Rights Act in a 2013 ruling. In that ruling, a 5-4 majority of the nation’s high court claimed checks on southern states’ attempts to suppress Black voters were outdated and no longer necessary.

“(Wray) said it was an error her predecessor had made a long time ago, and I said, ‘why are they changing it now?’” Mann told the Mississippi Free Press on Wednesday. “And she said, well, they just got around to changing it.”

Mann said that Wray later insisted that all questions about the precinct change must go through Flatgard, the attorney. The Democratic candidate said when she spoke to Flatgard, he said that the DOJ had ordered the precinct change, not recently, but under Wray’s predecessor, but that it had never happened. Wray took office in 2015.

Mann said Flatgard told her Wray wanted to make the change this year, but decided to wait until after the primaries to implement it. Mann also said Flatgard told her that the circuit clerk was not required to present the change to the election commissioners or the Board of Supervisors for approval, nor to make a public statement.

The Democratic candidate told the Mississippi Free Press that the approach contrasts with nearby Jackson and Canton’s approach to precinct changes, who advertised them with ample “signage and publicity.” During a press conference on Tuesday, Mississippi Secretary of State Michael Watson said that local elections officials are supposed to ensure voters are notified and that adequate signage is posted at the old polling location whenever they move voters.

Mann said the Flatgard sent her a map showing her which voters were being moved to the apartment precinct and provided her with numbers, which she then provided to the Mississippi Free Press.

Mann also shared several email exchanges she had with Flatgard with the Mississippi Free Press, including one on Oct. 24 in which he said officials were “working with The Mark Apartment management to try and make election day go as smoothly as possible with an anticipated high voter turnout (e.g., more parking and improved voter flow).” He did not explain how the officials planned to expand parking, though.

In another email, Flatgard told Mann that there “should be about 5 polling booths,” but that the commission was still “in the process of sorting through all of the polling booths in storage and making final allotments to polling locations.”

But Mann said she still thinks the summertime precinct change makes no sense.

“Why the timing? Why right now before a federal election?” Mann said.

She offered her own theory.

“My view is that this is being done to discourage minorities from voting,” she said. “These streets and these apartment complexes, and I can tell you having gone through all of them and knocking on doors in this area, are vastly majority African American.”

The Mississippi Free Press examined data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, which estimated population and demographic data for the area as of 2018, on CensusReporter.org.

The data show that Madison election officials moved Block Groups 1, 2, 4, and 5 of Census Tract 301.08 from the Ridgeland Recreation Center precinct to the Mark Apartments precinct; the US Census Bureau estimates 4,709 people reside within these block groups, including many who are not registered voters or not eligible to vote. Only 21% of them are white. The area, which is 0.9 square miles, includes 42% of the entire non-white population for District 1.

‘Jackson’s Rot’

The part of Ridgeland where local officials redrew the boundaries for the Mark precinct has a sordid past when it comes to racism. In 2016, several residents who lived in apartment complexes in southeast Ridgeland, backed by the Mississippi Center for Justice and the legal group Venable LLP, filed a complaint against the City, alleging racially discriminatory Fair Housing Act violations.

“The City of Ridgeland, Mississippi, has unlawfully attempted to diminish its minority population by eliminating, through rezoning, at least five apartment complexes that are occupied by predominantly African-American or Latino residents,” the 2016 complaint began, claiming that officials believed that “limiting affordable housing options was the best way to curb the influx of what was referred to as ‘Jackson’s rot.’”

That referred to a 2007 email that Alan Hart, whom the City had put in charge of planning the early stages of redevelopment efforts in southeast Ridgeland, sent to Nathan Gaspard of Moore Planning Group.

“County Line Road … would serve as a strong buffer, like the Natchez Trace does. The perception of property above the Trace is that it is protected from Jackson’s rot,” Hart wrote.

The complaint cited five apartment complexes by name that officials had allegedly targeted: Baymeadows Apartments, Sunchase Apartments, Oakbrook Apartments, Pinebrook Apartments and Northbrook Apartments. Four of them were located in the area that, until July, was part of the Ridgeland Recreation Center precinct; they have since joined Oakbrook Apartments as part of the Mark Apartments precinct area.

The 2016 complaint cited a number of comments made by local officials, including then Ridgeland High School Principal Lee Boozer who the complaint alleges said at a 2009 meeting of Ridgeland’s Community Awareness Committee meeting that “the images of the demographics is what needs to be battled” to help Ridgeland’s schools. Another member of the CAC “brought up the negative perception that goes along with free lunches for students,” the complaint said.

The 2016 filing also cited emails that Ridgeland Mayor Gene McGee received blaming “the apartment dwellers” and saying “something should be done IMMEDIATELY to reduce them” to stop falling “home values,” “deteriorating” schools and “the City’s decline.”

In another letter from constituents that McGee received in June 2009, two constituents warned that “the Ridgeland School demographics have changed significantly over the last five years” and the Ridgeland could “become the new Northeast Jackson,” with most white students attending private schools instead of public ones.

The mayor replied back, saying he understood the concern and that the City was “aggressively developing a strategy for near-term improvements that involves redevelopments of older apartments into single-family housing.”

Those plans included, at one point, an effort to demolish the majority Black and Hispanic southeast Ridgeland apartments and replace them with “new, single family housing units called ‘cottage clusters.’” The new housing units would have been outside the price range for many of the area’s non-white residents.

The complaint cited other emails McGee wrote back-and-forth with constituents.

“Although very utilitarian, doing the greatest good for the greatest number will not benefit Ridgeland or its citizens,” one wrote. “I agree,” McGee replied.

“The problem with Ann Smith Elementary is demographics, first, last, and always,” another constituent wrote. “You are so correct,” the mayor responded.

From White-flight Haven to Racially Diverse

Ridgeland’s population exploded in the 1970s and 1980s as white families fled the capital city over the desegregation of public schools. Ridgeland annexed the southeastern corner, which includes the precincts currently at issue, from Jackson in 1981.

Despite the area’s history as a white-flight haven, though, since the year 2000, though, Ridgeland’s population has grown increasingly diverse. In 2000, 76.3% of Ridgeland’s 20,000 residents were white; by 2010, the white share of the city population had fallen to just 57.5%. Meanwhile, its Black population bloomed over that decade, from 3,700 African American residents in 2000 to almost 8,000 in 2010.

Most of the non-white residents who moved to Ridgeland during that time moved to southeast Ridgeland, opting for affordable housing in the Southeast Ridgeland apartment complexes. By 2010, that area contained 68% of Ridgeland’s non-white population.

That year, in August 2010, constituents were still urging the mayor to do something about the majority non-white apartment complexes.

“No apartments mean no migration from Jackson by a race running from their own people … moving into white neighborhoods spells trouble, especially rental properties and apartments. Where they go trouble follows, always has and always will,” the constituent wrote.

The mayor responded sympathetically: “I vigorously fought those apartments and tried to be sure that properties were not re-zoned for apartments for many years. … What you don’t know is that I am also working to get rid of a large number of apartments right now.”

‘It’s Racially Motivated’

Throughout the first half of the last decade, the City and its all-white Community Awareness Committee made several attempts to redevelop the southeast part of the city and to price out many of its non-white residents. After implementing an “aggressive code enforcement regime” that targeted the southeastern apartment complex, the city in 2014 passed a zoning ordinance that made it almost impossible for those apartments to come up to code.

That move triggered not only the 2016 lawsuit, but also caught the attention of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which investigated the city and alleged it had engaged in “unlawful discrimination based on race in its ongoing amortization, condemnation, and threatened removal” of the five apartment complexes.

In September 2016, the City settled with HUD, agreeing to grandfather the pre-existing apartments’ non-conformities into the new zoning rules, allowing them to stand. In a September 2016 statement, the City claims its goals had been noble.

“In its zoning actions, the City sought to ensure and improve the health, safety and welfare of its citizens, regardless of race, including the citizens of the affected apartment complexes. The City remains committed to that goal,” Ridgeland said in a statement at the time.

On Wednesday, Carol Mann cited the fight over the apartment complexes in the area as an example of how officials have long “targeted” the area with race-based schemes.

Steve Cunningham, the African American voter who said he has voted at the Ridgeland Recreation Center precinct since at least 2008, told the Mississippi Free Press that he believes the latest precinct change is another such effort.

“I absolutely, 100% think it’s racially motivated,” he said.

This story is part of the MFP’s Mississippi Trusted Elections Project, focusing on access to the polls and voting access in Mississippi. Visit the site to view several infographics and continually updated maps of voting precincts, absentee vote totals and precinct changes across Mississippi, created by William Pittman who also did data analysis for the above report. The American Press Institute provided funding for this work.