“Oh, she’s going to kill us.” That was the gist of the conversation, Marion Barnwell recalls, when their committee selected Ann Abadie for the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters 2020 Noel Polk Lifetime Achievement Award.

Abadie notoriously favors a background role. She was deeply embedded in the founding of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and the Southern Foodways Alliance at the University of Mississippi, associate editor of “The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture” and “The Mississippi Encyclopedia” and more.

“She really resists this kind of stardom,” Barnwell says.

But in the year prior, SFA pulled back the curtain to shine the spotlight on Abadie, with the 2019 Craig Claiborne Lifetime Achievement Award. The institute, too, wanted to champion Abadie, a past president and longtime board member, as well as a detail-driven, steel-willed backbone in so many cultural pursuits. “She just is absolutely dedicated to any artistic and creative endeavor, and wants to support it in any way she can,” Barnwell says.

Abadie’s preference? More backstage than center stage. “I do better just writing proposals and working behind the scene, and writing letters and encouraging people to do this or that,” Abadie says. A video spotlight for her SFA award sings her praises stronger, as colleagues describe her savvy way with suggestion, her relentless encouragement, her sharp determination and her crucial roles in projects that engaged academia with a popular audience.

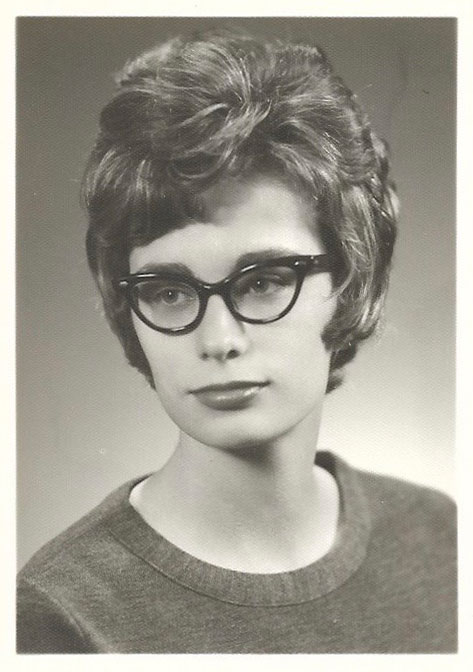

“I’m touched and thrilled” with the acknowledgements, says Abadie, now 81. Retired from the University of Mississippi since 2011, she lives in Oxford with her husband, Dale, former dean of UM’s College of Liberal Arts.

A South Carolina native, she was an English and history major at Wake Forest College (now Wake Forest University) in North Carolina, when her attention got wrapped up in history unfolding all around. “I was very involved with what was going on, and I was very interested in the Civil Rights Movement when I was in Winston-Salem. The sit-ins had started at Greensboro, about 30 miles away.”

She didn’t participate, but was keenly aware and interested. “The whole business of the South and what it is and how it’s different from the rest of the country and the world … that sort of interested me, along with my study of literature.”

On the literary front, “I just fell in love with William Faulkner’s writing,” she says, remembering the little paperback with “As I Lay Dying,” and then “The Sound and the Fury.”

“I loved the way he wrote about people, and the way he challenged the reader to figure out what in the world is going on, and that he wrote about not just the wealthy people, but the African Americans and the poor whites,” she says. “He saw the whole world.”

A National Defense Education Act fellowship brought Abadie to Oxford for graduate school in 1960. “That was the days before ordinary people could fly,” so she had to get a driver’s license and an old car to make that road trip from South Carolina’s Upcountry to Mississippi. “I was here just a few days when I saw Faulkner sitting on the front porch with his mother, in the house where Dean Faulkner lived on South Lamar, so that was thrilling.”

Abadie never really met the Nobel Prize-winning author. On occasion, she’d see him walking back and forth from Rowan Oak to the Square, would greet him with “Good morning, Mr. Faulkner” and get a tip of his hat in return. Faulkner’s life ended in 1962, but his writings continued as a touchstone in hers.

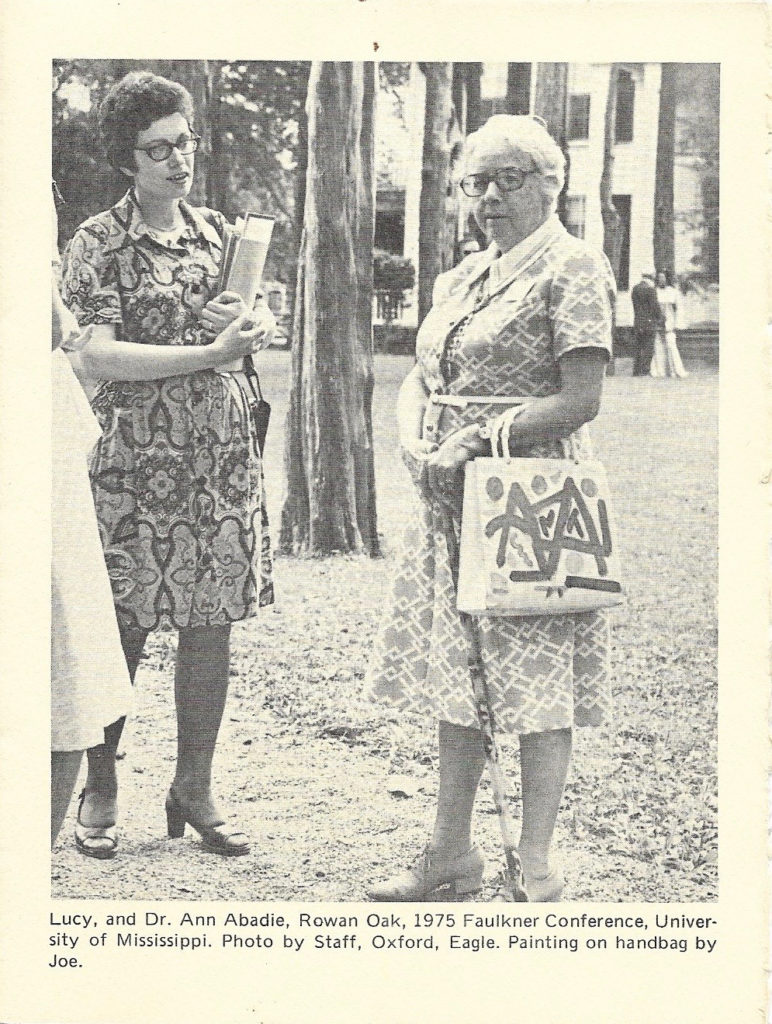

By the early 1970s, Rowan Oak was open to the public. As Faulkner admirers continued flocking to Oxford, it fell to a small cadre of university faculty to show them around Faulkner country. Abadie relayed Rowan Oak curator James Webb’s “we’ve got to do something” request to a carload of colleagues on a trip to Jackson in support of Mississippi Educational Television in February 1974. By the time they got home, “we decided, oh, we would just have a conference and let everybody come at once.”

Joseph Blotner (his “Faulkner: A Biography” was brand new), Elizabeth Kerr (“Yoknapatawpha: Faulkner’s ‘Little Postage Stamp of Native Soil’”) and Malcolm Cowley (“The Portable Faulkner” editor) were invited as speakers. They turned a bit of promotional money into a 1-by-1½-inch ad in The New York Times Book Review.

“Just a little tiny thing,” Abadie says, with just enough room for a Faulkner pic, conference dates and a phone number. “Well, the phone started ringing off the hook.”

Hundreds wanted to come, so to keep it intimate, they held a conference, then repeated the same thing the next week—the practice for those first two years. Scholars and locals filled the panels, “and we had just a grand week.” They even took folks to Ripley (where Faulkner’s family had lived), where the citizenry was so excited they rounded up the high school band to play on the town square.

Abadie was coordinator of the Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference 1974-2011, edited “William Faulkner: A Life on Paper” (1980) and co-edited dozens of books in the conference series, up through 2016. Her interest in the author never wanes. “I love to read and reread Faulkner, just as I love to read and reread Eudora Welty.”

‘Ole Miss to Study Grits’

The 1970s also saw the start of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the university. Abadie was part of the 20-member committee that formed it. She wrote the grant proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities for a consultant at the start—a successful pitch highlighting the importance of regionalism and Mississippi as the epitome of southern and American culture because of the triumphs and the tragedies of the human spirit embodied here, from slavery and Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement.

The second NEH grant, to develop its interdisciplinary southern studies program, “the first big grant they had given in the South” was big news. “The headline in the L.A. Times was ‘Ole Miss to study grits,’” Abadie says.

While the center’s directors have been the most public front folk—Bill Ferris, Charles Reagan Wilson, Ted Ownby and (since July 2019) Kathryn McKee—Abadie was a steadfast presence in its first decades, as its acting director at the outset, and associate director 1979-2011.

That grits headline proved prescient. The center became the incubator and base for the Southern Foodways Alliance in 1999, and Abadie was among the founding directors. The alliance was rooted in the broad, diverse focus of author/activist John Egerton, who convened the first organizational meeting in Birmingham. Seed money for its start came from the center’s cookbook “A Gracious Plenty” that John T. Edge (then a grad student at the center and soon SFA’s founding director) worked on.

Abadie strapped on another role for the SFA’s first Oxford meeting. “John T. was going to have all the board at his house for dinner, and I said I would help cook, so I made a huge amount of Craig Claiborne’s mother’s favorite chicken spaghetti,” she says. “It is wonderful. … Make sure you know you’re going to use every pot, pan and dish in the kitchen.” That’s even for just one batch, feeding 10 to 12. That Oxford dinner fed 40 to 50.

She is proud, too, of her coordinator roles in the Oxford Conference for the Book, 1993-2011, and in 1987’s “Covering the South: A National Symposium on the Media and the Civil Rights Movement” and 1989’s “The Civil Rights Movement and the Law: A National Symposium.”

‘Just a Series of Accidents and Incidents’

Abadie joined the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters’ board of governors in 2007. “I love working on it,” she says, with its focus on fiction and nonfiction writers, classical and contemporary musicians, visual artists and this year’s new category of youth literature. “It has really brought a lot of attention to the state and its great accomplishments in the arts and letters, so I’m very proud of the organization and what it’s done,” she says.

She’s quick, too, to laud founder Noel Polk’s insistence, at the institute’s start, to give awards to living writers and artists for current works, “which has turned out to be a great thing,” she says. She chuckles as she envisions “Noel’s flapping his wings in heaven right now” at an acknowledgement of the awards’ distinguishing hallmark.

Abadie describes her own path as “just a series of accidents and incidents.” The direction they led became a career that delved deep into regional history, literature and culture, brought people together in that quest and built a trail of books along the way.

Even in retirement, projects entice her book expertise. She edited the first two in a series connected with the University of Mississippi Museum (where she’s a board member) and published through University Press of Mississippi—”The Beautiful Mysterious” on a William Eggleston exhibition (published 2019) and another on the landscape in art and literature, now in the works. “My last book ever,” she claims, then talks up the need for one on artist Theora Hamblett, “one of the next ones they do, I hope.”

As history shows, the power of Abadie’s suggestion and push of her encouragement can be momentum enough to get it done.

____________

Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters’ 2020 Award Winners

The Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters’ annual gala banquet was postponed until 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Category awards honor works published, performed or shown in the previous year. Here is the full list of MIAL’s 2020 award winners:

Noel Polk Lifetime Achievement Award: Ann Abadie

Special Achievement Award: Mississippi Delta Tennessee Williams Festival in Clarksdale

Citation of Merit: Lemuria Bookstore in Jackson

Visual Arts: Stacey Johnson of Pass Christian, for the exhibit “Storytellers”

Photography: Will Jacks, a native of Cleveland, for “Po’ Monkey’s: Portrait of a Juke Joint”

Poetry: C.T. Salazar of Caledonia for “This Might Have Meant Fire”

Classical Music Composition: Steve Rouse, a Moss Point native now of Louisville, Kentucky, for “The Bird, the Bee, and the Bear”

Fiction: Minrose Gwin, a Tupelo native now of Albuquerque, N.M., and Austin, Texas, for “The Accidentals”

Nonfiction: Margaret McMullen of Pass Christian for “Where the Angels Lived: One Family’s Story of Exile, Loss, and Return”

Contemporary Music Composition: Bark (duo Susan Bauer Lee and Tim Lee, native Mississippians), for “Terminal Everything”

Youth Literature: Angie Thomas, a Jackson native, for “On the Come Up”