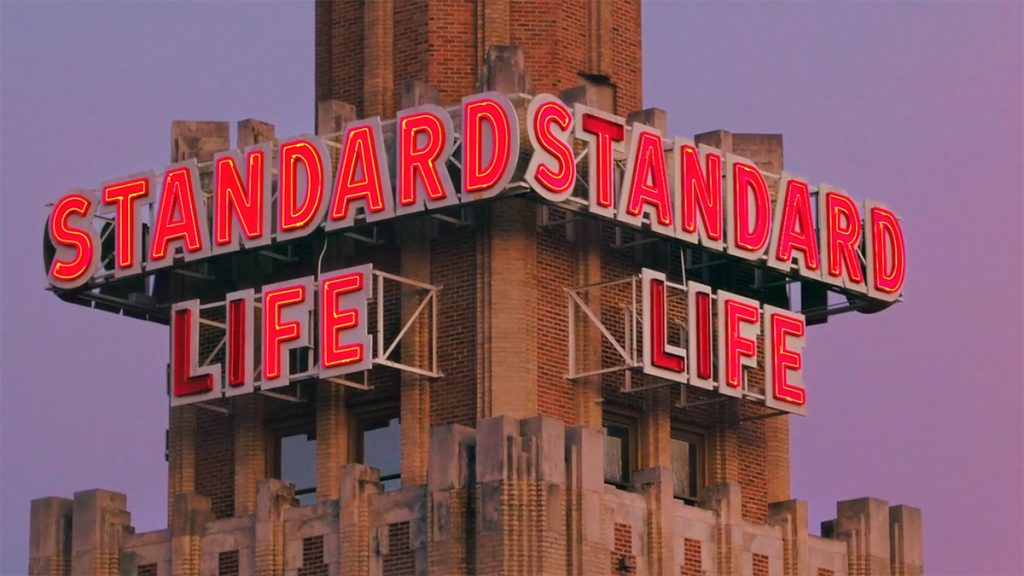

The Standard Life building, a highrise in downtown Jackson, is one of the tallest buildings in the city. At night, its name shines brightly in bold, red lights at the top of the structure. And it’s one of the last images the audience sees toward the end of director Alex Warren’s short documentary “Fertile Ground.”

As the camera pans around the building, documentary producer Jocephus “Skipp” Martin recalls a conversation he had with a man about the building. “What does it mean to have a standard life, to live in one of the richest countries on the planet, and all you get is this poverty, pain and suffering?” the man asked.

As the camera pivots around the top of the building, if you look closely, the L and I in “Life” are muted, the color a deeper, darker red compared to the other letters that surround it. Of course, the bulbs have died. But to the question of what is a standard life? For some, it’s like those dead light bulbs. It’s not bright. It’s bleak because they don’t have the same opportunities and access as others.

“Fertile Ground” explores Mississippi’s agricultural industry and food inequality in Jackson, the latter of which is made clear in the documentary’s opening scene, which follows a man’s long journey to get to a quality grocery store. He doesn’t have a car and travels by bus, the main two modes of transportation in a city with few sidewalks and no bike lanes.

The man has to take a 20-minute bus ride downtown and wait for a transfer to get to Kroger. He needs to take two to three trips to get everything, and a one-way bus ride is $1.50. Three round trips is $9, and he can’t afford that. And he’s walking in the rain with a Save-a-Lot grocery cart.

‘Historical Ramifications of Redlining’

Mississippi is hungry. It’s No. 1 in food insecurity but a leader in agriculture. The capital city has more than 70 fast-food restaurants and more than 150 gas stations. Sixty percent of food Mississippians eat comes from outside the state.

It is one of the only states in the country that still has a 7% sales tax on groceries. On average, a family in Mississippi pays about $600 more a year on groceries because of the tax.

But for all of this, there are still Mississippi communities living in food deserts, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as low-income areas with a significant number of residents with low levels of access to retail outlets that sell healthy and affordable foods.

If you head into north Jackson, Madison or Flowood, you’ll find multiple grocery-store chains—Whole Foods, Walmart, Kroger and even smaller chains like Corner Market. You’ll find gas stations and fast-food chains, sure, but you’ll also find a variety of dine-in restaurants and other businesses with healthier food options.

“A lot of this (is) due to historical ramifications of redlining, where it makes it a high-risk environment for these grocery stores to come in and open up locations because it’s too expensive, or they won’t get insurance to open up grocery stores in these neighborhoods,” Fertile Ground Project Manager and City of Jackson Urban Designer Salam Rida said in the documentary.

Martin, the producer, used to work at the Kroger on Terry Road in south Jackson, but it shut down in 2015. The community recently lost its Walgreen’s and McDonald’s. Those businesses leaving take jobs and community income with them but also food in a city where hunger is common, even if not the healthiest options.

“What happens here in south Jackson is what happens everywhere. You have white flight. Then you have economic flight, and after you have that, it gets abandoned. Some communities are deemed better or more valuable than others. Those people get to keep access to food that doesn’t give poor, black people access to healthy institutions. That’s just not what poor, working -class Black people get in America,” Martin said.

Brimming with Potential and Solutions

The documentary also explores hunger’s impact on structures like the prison and school systems. Activist Bilal Qizilbash says homeless people are aware of the types of crimes that they can commit to get the prison time that gets them off the streets and solid meals.

Community organizer Melishia Brooks says children aren’t getting the basic nutritional needs in their school lunches and snacks, which can curtail their focus and academic performance in school. Not to mention, for some children, that might be the only meal they get for the day.

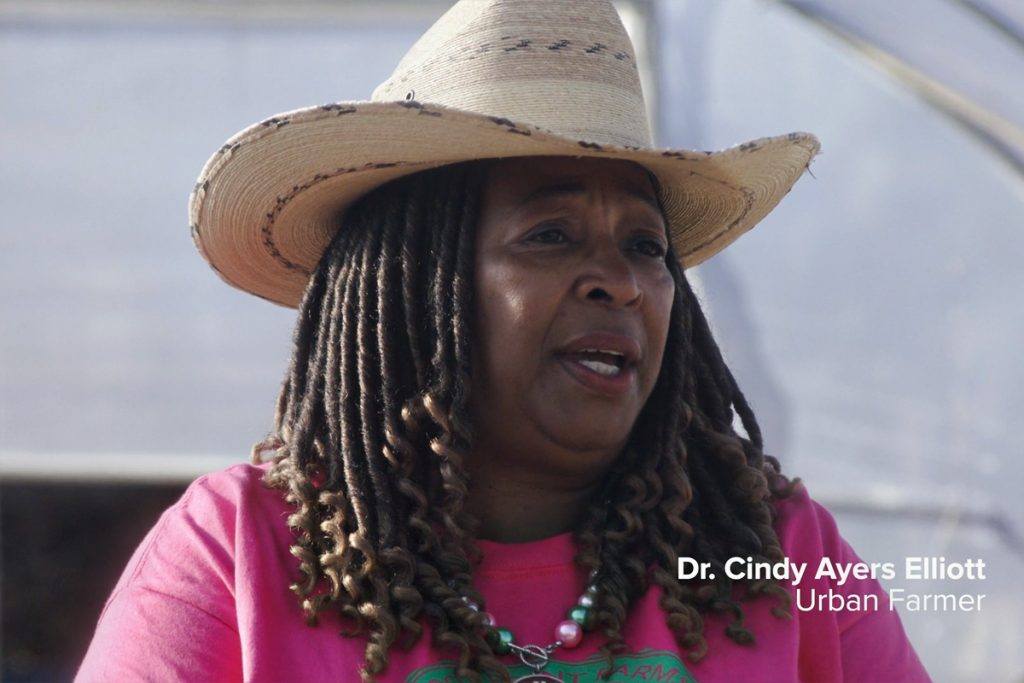

Mississippi may be hungry, but it’s not for lack of food. It’s for lack of change, and people like Cindy Ayers, Qizilbash’s Draw A Smile foundation, the Fertile Ground Project and many others are fighting for food access.

Ayers founded Footprint Farms in 2010, a 68-acre specialty farm in Jackson that grows fresh fruits and vegetables and raises livestock like chickens, cattle, horses and meat goats. The farm focuses on agri-tourism for community development in Jackson.

“I believe that growing in your backyard, in your coffee can, that you can make a difference, and you can live healthier. It’s not about just putting seeds in the soil. It’s about putting seeds in the minds,” Ayers said in the documentary.

Dr. Ayers is also focused on educating farmers, particularly small, Black farmers, about the policies and programs that exist for them.

She’s also chalk full of solutions to help bring healthier options to the communities stuck in food swamps, areas with establishments that sell high calorie fast-food and junk food.

“What we don’t have and we don’t do in Mississippi is to be able to have value added to put healthy foods on those shelves. We can have an option for them in those stores if we had the foresight to look at doing value added and utilizing that as a distribution place, instead of a food swamp,” she told the Mississippi Free Press on July 27.

“I see opportunity in that, and that’s what I’d like to work on.”

‘We Weren’t Afraid of Them’

Activist and Draw A Smile co-founder Bilal Qizilbash started the R U Hungry? project, which offers free, hot meals to anyone who needs it (homeless or not) at Smith Park in downtown Jackson. The organization has fed between 70 to 170 people at one time.

“We weren’t afraid of them. We recognized them for their soul and humanity. The most important thing that is missing in this entire system is love. A lot of people don’t ever get that,” Qizilbash said of the homeless people the organization feeds.

Fertile Ground, the city’s project, examines urban food access through art, film, performances and installations throughout the city. The exhibition was supposed to happen in April, but the COVID-19 pandemic curtailed events; however, the education and work isn’t stopping.

“Jackson is the prime location in so many ways for green infrastructure. Green infrastructure is essentially developing food, water, energy and waste systems in cities that are taking industrial zoning or commercial zoning and transforming those pieces of land into a productive landscape,” Travis Crabtree, an urban planner for the Fertile Ground Project, said in the documentary.

The potential is there. It’s all about what we do with it. No one should go hungry and hopefully, a few years from now, no one will.