PHILADELPHIA, Miss.—After the Mississippi Legislature voted to ditch the state’s Confederate emblem-bearing flag on June 28, Tiffon Moore noticed two distinct responses from white Mississippians in Neshoba County.

Some one-time apologists changed their minds about Confederate iconography. The new way of thinking, Moore says, went something like this: “You know what? There is a point where people are upset about this. And why should this flag be flown, especially if we’re patriotic Americans? This flag is a representation of unpatriotic Americans.”

“For many of them, it has changed their perspective,” said Moore, who is president of the Philadelphia-based Black Empowerment Organization and is now focused on moving the Confederate statue from the courthouse grounds.

Other white Mississippians took a different line about removing Confederate symbols 155 years after the South lost the Civil War to the United States. Abandoning the flag was the “first strike,” they say.

‘A Special Ceremony’ Honoring the Repaired Statue in 2006

The Confederate monument outside the Neshoba County courthouse is hard to miss. Grayed white, 11 feet tall and adorned with lights to scare off any nighttime vandals, it is the courthouse yard’s showpiece. Dedicated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1912, it bears resemblance to Confederate statues across Mississippi. A young rebel holds his rifle in staff position as he gazes into the distance, shading his view with a cupped hand.

Neshoba County invested $1,000 into putting up the statue, and locals contributed the same amount through public subscription. Its plaque pays homage to more than a dozen units from Neshoba County who fought for the Confederacy. The statue pays “tribute to the noble men who marched ‘neath the flag of the Stars and Bars and were faithful to the end.”

When the statue first went up, the Neshoba Democrat reported that the statue of the rebel soldier “is hewn from the whitest of Italian marble” by a sculptor in Italy.

In 1990, a windstorm damaged the unnamed rebel’s hand, arm and hat brim, and he was kept inside the courthouse. When a restoration committee raised more than $13,000 to repair and update him in 2006, he became the main attraction at an annual festival.

“This year’s Autumnfest festival will not only include music, food and art contests but also a special ceremony officially dedicating the newly restored Confederate monument on the courthouse lawn,” the Neshoba Democrat reported on Oct. 11, 2006. Other festival fun was paused to guarantee there would be no interruptions to the ceremony. A bagpipe player and Civil War reenactors sparked new life into the old, battered rebel.

‘From a Place of Love, Not Hate’

Philadelphia’s history has its share of “good parts” and “pretty tough parts,” Tiffon Moore, 29, noted.

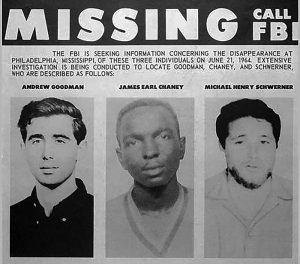

In 1964, Ku Klux Klan members, Philadelphia police and Neshoba County deputies conspired to kidnap and murder civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner after the three young men left the site of a county church east of town that the KKK had burned. County Road 515, where the mob shot the men—a Black man from Meridian and two white men from New York City—is nine miles south from the courthouse and the statue, just off Highway 19 South. The FBI fittingly filed the case as MIBURN, or “Mississippi Burning.”

In 2004, on the 40th anniversary of the murders, the Philadelphia Coalition—Black, white and Choctaw Neshobans—publicly called for anyone with information on the murders to come forward. Former Secretary of State and Neshoba County native Dick Molpus gave an impassioned speech. “I believe … until justice is done, we are all at least somewhat complicit in those deaths,” he said at the time. Then-Gov. Haley Barbour sat right behind him.

Molpus had been the first state official to apologize to the three men’s families for the murders on the 25th anniversary in 1989.

Six years later, when he was running for governor, incumbent Gov. Kirk Fordice chided Molpus for that apology during a debate at the Neshoba County Fair. “I’ll tell you this,” Fordice said. “I don’t believe we need to keep running this state by ‘Mississippi Burning’ and apologizing for what happened 30 years ago. This is the ’90s. This is now. We are on a roll. We’ve got the best race relations in the United States of America.”

Molpus responded, “I apologized to the family, the mother and father and sisters of those three young men who lost their life in Mississippi,” adding, “I make no apologies to you about that. … Kirk Fordice leads more by venom than vision.” But Fordice, also known for courting the racist Council of Conservative Citizens for votes, won the race.

After the Philadelphia Coalition’s work across race lines, in 2005, Edgar Ray Killen, a 1964 Ku Klux Klan leader and preacher who masterminded the plot, was convicted on three charges of manslaughter the next year. He died in Parchman Penitentiary in 2018.

Historians Eric Foner and John Garraty describe the Mississippi Burning murders as precipitous to the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which guaranteed voting protections for Black Americans.

‘I Am a Descendant of Slaves’

Today’s national movement against racism and police violence inevitably came to Neshoba County. When Minneapolis, Minn., police knee-choked George Floyd in late May, Moore and other activists formed the Black Empowerment Organization to foster social, racial and economic justice locally, she said. After Petal Mayor Hal Marx tweeted that there was nothing “unreasonable” in Floyd’s death—likely the result of an overdose or a heart attack, the mayor mused—the group organized a protest on Neshoba County’s courthouse steps in solidarity with Petal.

“We noticed the statue was there, so we had a discussion about it, along with citizens in our community,” Moore said.

On July 4, BEO started a Change.org petition to remove the statue from the courthouse. The initial goal was 200 signatures. At press time it has more than 500, and the new goal is 1,000.

“I am a descendant of slaves, and it definitely pushed me to want to see this monument placed in a museum,” Moore said.

Moore’s ancestors were Yoruba and Igbo captured in Africa and brought to Virginia. They were sent to a plantation in South Carolina and later to the Mississippi Delta and Alabama. They migrated to the Kemper County and Preston areas.

Living in Philadelphia and later attending the University of Mississippi shaped her understanding of race and racism, she said.

“I have a biracial child,” Tiffon Moore said. “Because of the environment in Philadelphia, a lot of things misled me. When I was 16, I got pregnant with my first child. I remember I was supposed to go to prom with my son’s father. I was not allowed to go with him, and my family believed it was for a prejudiced reason.”

Moore going to prom the next year was sullied when someone at a local nail salon called her and her aunt “n*gger,” she said.

“When I went to the University of Mississippi, it kind of changed my perspective,” she said.

In 2012 white UM students angry over President Barack Obama’s re-election burned campaign signs, shouted racist slurs and won the attention of national media.

Recently, Moore has reported death threats against BEO members to the Philadelphia Police Department after a Facebook stranger shared pictures of his gun collection with her, she said. She is considering reporting the threats to Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch.

Mother: ‘She’s Standing in the Gap’

Despite the threats, Moore’s mother, Tiffany Moore, supports her daughter’s effort and helped her and her nephew Malek Moore, 24, organize the group. “When Tiffon started this journey, I was a little worried,” Moore, a store manager, said. “But I realized that an apple doesn’t fall far from a tree.”

Her daughter’s work matters, she added. “(Tiffon is) standing for so many who feel the same way, but are afraid to speak. She’s standing in the gap for those in Neshoba County who have been mistreated because of the color of their skin. Not only am I proud of her, I’m proud of my nephew Malek Moore who has stood right beside her.”

“When I was in my early teens, I started going on civil-rights tours,” Malek Moore told the Mississippi Free press. “One of my first was in Philadelphia. It had me emotional. I was oblivious to (the history), and it opened my eyes.”

“Especially for Neshoba County, the importance (of the protests and statue petition) was to show that our county, our city, is willing to take a step forward towards unity and justice for all,” he said. “It has a cruel history with blacks being oppressed. To see the statue taken down would mean that, hey, this city is willing to take the next step. You can’t erase the past, but you can definitely make the future better.”

As BEO’s vice president, Malek Moore focuses on outreach. The group has done everything from organize kickball games to register voters.

“We have a board,” he said. “We don’t want to be a dictatorship. Everyone brings ideas. We have a monthly fee, and everyone helps out in their own way.”

Regardless of the response from some white Mississippians, BEO is organizing “from a place of love, not hate,” Tiffon Moore said. “We want to include everyone. We want everyone to stand with us.”

BEO’s vision statement says its focus is “African American History, Voters Registration, HBCU insight (including minority scholarships), Financial advisement, Civil Rights History, Black owned Entrepreneurship, and History of Criminal Justice within black and minority communities.”

One Supervisor for the Move, Another Against, Three Quiet

The BEO will present its petition to Neshoba County’s board of supervisors later in July, asking for the statue move. The Mississippi Free Press reached out to the county’s five supervisors for comment. Two responded.

“I’m for keeping (the statue) where it is,” white District 3 Supervisor Kinsey Smith said.

“You ask those people that want to move it, did any of their fathers or grandfathers go and fight for our country?” he instructed a reporter. “Did they go and die for our country?”

The Confederate States of America seceded from the United States and considered itself a separate country, fighting U.S. soldiers in the Civil War.

Smith added that he fought in the Vietnam War, and his father fought in World War II.

At least one veteran disagrees with Smith’s view on patriotism and the monument.

“I have spent quite a few hours lately researching monuments and especially Confederate monuments,” District 5 Supervisor Obbie Riley told the Mississippi Free Press. “To this point, all of the information that I’ve been able to read has those monuments placed in a time in our history when they were basically pro-segregationist, and it does not represent the community as a whole. I think it’s probably inappropriate to display Confederate monuments on state or federal property unless they are in a museum or a park that’s designed to teach history.”

Riley, who is the only Black Neshoba County supervisor out of five, has wondered whether the soldier on Neshoba County’s monument is doing a left-hand salute or simply guarding his eyes from the sun as he searches for Yankees.

A Dec. 12, 1912, article in the Neshoba Democrat offers an answer: “The soldier has his hand elevated to his brow as if looking for the blue coats in the far distance,” it reads.

“Me being a military man, I think all war archives should be treated like others,” Riley said. “This is paying homage to a lost war. I think those monuments should be treated just as you would treat those of any defeated nation.”

“Saying I don’t believe it belongs on the courthouse square is not in a divisive way but an inclusive one,” he stressed.

Though a Mississippi law states that no war monument may be “relocated, removed, disturbed, altered, renamed or rededicated,” it adds that a governing body may move the memorial to a “more suitable location if it is determined that the location is more appropriate to displaying the monument.” At least four county boards in Mississippi have voted to move Confederate monuments away from courthouses following June’s state flag vote.

Riley said he will support relocating the monument where its context and history can be better understood “if it’s legal.”

“This is a history that should be remembered,” Tiffon Moore said. “But the statue should not be placed in front of the Neshoba County Courthouse. A courthouse is a place where you can receive justice.”

How, she asked, could someone receive justice at a courthouse marked by a symbol of injustice?

Read Mississippi Free Press coverage as efforts to move Confederate statues and memorials grow across the state. See an infographic of Confederate memorials in Mississippi and report missing ones to data@mississippifreepress.com.