One of my favorite reporting trips ever was touring around Noxubee County with then-freelance writer Torsheta Jackson in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because she grew up in East Mississippi county, over on the Alabama border, Torsheta was the tour guide, driving us around in her big truck I had to lift myself into. First, she showed me where she grew up in Shuqualak, the child of educators. Along the way, she pointed out slabs where industry, grocery stores and schools used to stand before her hometown became a shell of its former self over the decades after forced integration in 1970.

We walked around the ruins that now dominate the little downtown next to the railroad tracks and talked about poverty, neglect, white-flight cycles and disinvestment in the county settled by rich white planters—including Mississippi State University founder Stephen D. Lee’s family—and built by enslaved Black people. The county has always been majority-Black, but usually under white control, from newspapers, to industry, to local education decisions and resources. It was also the site of vicious white terrorism to keep it that way.

In the county seat of Macon, Torsheta showed me the county’s only remaining grocery store—white-owned and too expensive in a county where hunger is far too rampant, she said. She took me to see the library with the gallows where they used to hang people right in the building in front of crowds on the front lawn, now marketed as a tourist attraction. We looked straight out the front window of the library at the tall Confederate statue standing in front of the courthouse across the street in the 82%-Black town. The Board of Supervisors voted in July 2020 to remove it; last I checked, it was still there as post-George Floyd anti-racism enthusiasm wanes.

Torsheta showed me the abandoned Central Academy, which the superintendent of the county schools helped open in the 1960s, supported by state vouchers, and became the seg academy’s headmaster within days. She drove me to all the now-boarded-up, or disappeared or repurposed, public schools that used to be in Noxubee (locally pronounced “Nock-shu-bee”) County before most white families fled either to C.A. or to the local Mennonite school, which opened in 1970 soon after forced integration.

Torsheta and I spent hours in the “new” Noxubee County public school just north of Macon talking to the principal and the school psychologist—both women she knew growing up there. They educated us about the perpetual state of crisis that faces the district and its one remaining public-school system for the entire county; district leadership was changing again that day, in fact.

Of course, we learned about the systemic challenges that face Black women and their families, in particular, in Noxubee County, from no broadband, to hunger, to mental health and more. The women’s honesty with us informed Torsheta’s award-winning installment of our “(In)equity and Resilience: Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” cause-solutions journalism project. It is now the prototype of our statewide county-level Mapping Mississippi systemic-reporting strategy that we’re amping up by summer with Torsheta’s help and inspiration.

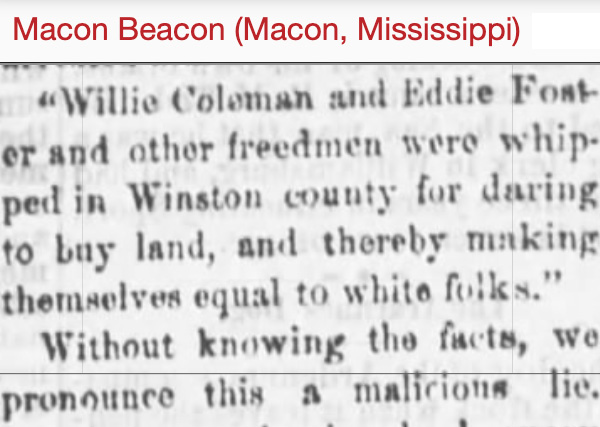

Not to mention, a new area of research opened up for me when I heard the school psychologist’s story about a mob of local white men killing a Black woman school principal to stop education and advancement of Black children. It was white terrorism deployed over many decades specifically to keep Black children uneducated and, thus, inequity and white control in place for generations to come. They said that they were doing for white-supremacy perpetuity right in the local newspaper. It wasn’t a secret. They bragged about and excused ugly mob race violence by county leaders designed to pay white supremacy forward.

It was an eye-opening and powerful journey for us both. Torsheta would later say on MFP Live that, before that reporting, she had not fully understood how intentional barriers and discrimination caused the decline of her home county over the decades. After this journey into the past, she did.

It was on that tour of Noxubee County that I decided that I wanted Torsheta as a full-time education-equity reporter to take her systemic journalism across the state and help me build our Education Equity Solutions Lab. This is a very different kind of education reporting than the partisan griping about schools and funding that we usually see in Mississippi.

For me, what I called Project Torsheta started on that trip. With her years of teaching experience (19 as of now), her brilliance, her curiosity, her wit and her stunning work ethic, I knew Torsheta was the kind of reporter Mississippi, and America, needs and deserves covering education. She can show us like no one else how education’s use as a political and control football hurts families, children and whole communities.

💥 We’re thrilled to welcome the newest member of our newsroom, Torsheta Jackson, a @Report4America corps member covering education equity. Torsheta is a Noxubee County native and teacher. Support our education equity work with a gift today. https://t.co/JD1H3eGc2e pic.twitter.com/rInXqbIqPp

— Mississippi Free Press (@MSFreePress) April 27, 2023

Fast forward a couple of years, and it’s happening. Report for America announced Wednesday that it is supporting Torsheta as our lead education-equity reporter to do this work, paying a chunk of her salary for the next two to three years. After two years of working together to figure out timing and resources, Torsheta and I—and our whole team—are ecstatic that our vision is happening. I simply cannot wait to develop this work with Torsheta, and it doesn’t hurt that I hired fantastic Business Manager Jared Norton to free me up for more journalism. Torsheta and I (and others) will soon be traveling the state together again, doing the systemic journalism we know can help improve this state for all of our people.

I’ll talk more soon about our second new reporter we announced this week. Heather Harrison of Copiah County is the vivacious and dogged outgoing editor of The Reflector at Mississippi State. I knew in our first conversation (and then confirmed in a team solution circle) that she is bringing the energy, passion and curiosity that it takes to succeed and thrive at the Mississippi Free Press. She’ll be our first regional full-time bureau reporter, remaining in Starkville to largely cover that region of the state and help us collaborate with the Starkville Daily News.

Needless to say, you readers are making all of this growth happen. We started with $50,000 and one full-time reporter just three years ago, and you have helped create soon 17 good-paying jobs and pay for myriad freelancers, contractors and interns—most brilliant and engaged Mississippi natives staying home to do the work.

Our resources are mostly from readers to date. You get it, and you are intentionally helping us grow our team and our reach to more counties. Please help keep us growing by giving what you can now at mfp.ms/donate. Remember, your recurring donations are paying for at least one reporter already, so every amount matters as we interrogate systems across Mississippi on the road to solutions.

Follow Torsheta Jackson at @TorshetaJ on Twitter.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Journalism and Education Group, the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.