As a child and student at East Side Elementary in West Point, Miss., Jayme Evans loved going to the school library, where the kindergarten librarian Elizabeth O’Brian would often help her check out extra books to read at school and home.

“I was the kid who always wanted to be in the library rather than anywhere else. And if I wanted an extra book, Ms. O’Brian made sure I could get it,” Evans recalls.

Now that Evans is the youth services librarian at the Bryan Public Library in West Point, she still sees her mentor. “Ms. O’Brian comes in pretty frequently, always looking for a Debbie Macomber book, and she’ll check on me if she hasn’t seen me for a couple days,” Evans says.

Although Evans, who grew up in West Point and reads as many as 10 books per week, headed to the public library with her mom when she wasn’t at school—even on Saturdays—she initially wanted to be a doctor. But the library called her instead.

“I started volunteering at the library my senior year at Mississippi State University, and fell in love with being in the community and around books all day,” Evans says now. “Former teachers would come in and ask me to recommend a book. For the longest time, they had been the people I would ask for help. Now, they were asking me. It was exciting. I could actually help the people who helped me grow as a person.”

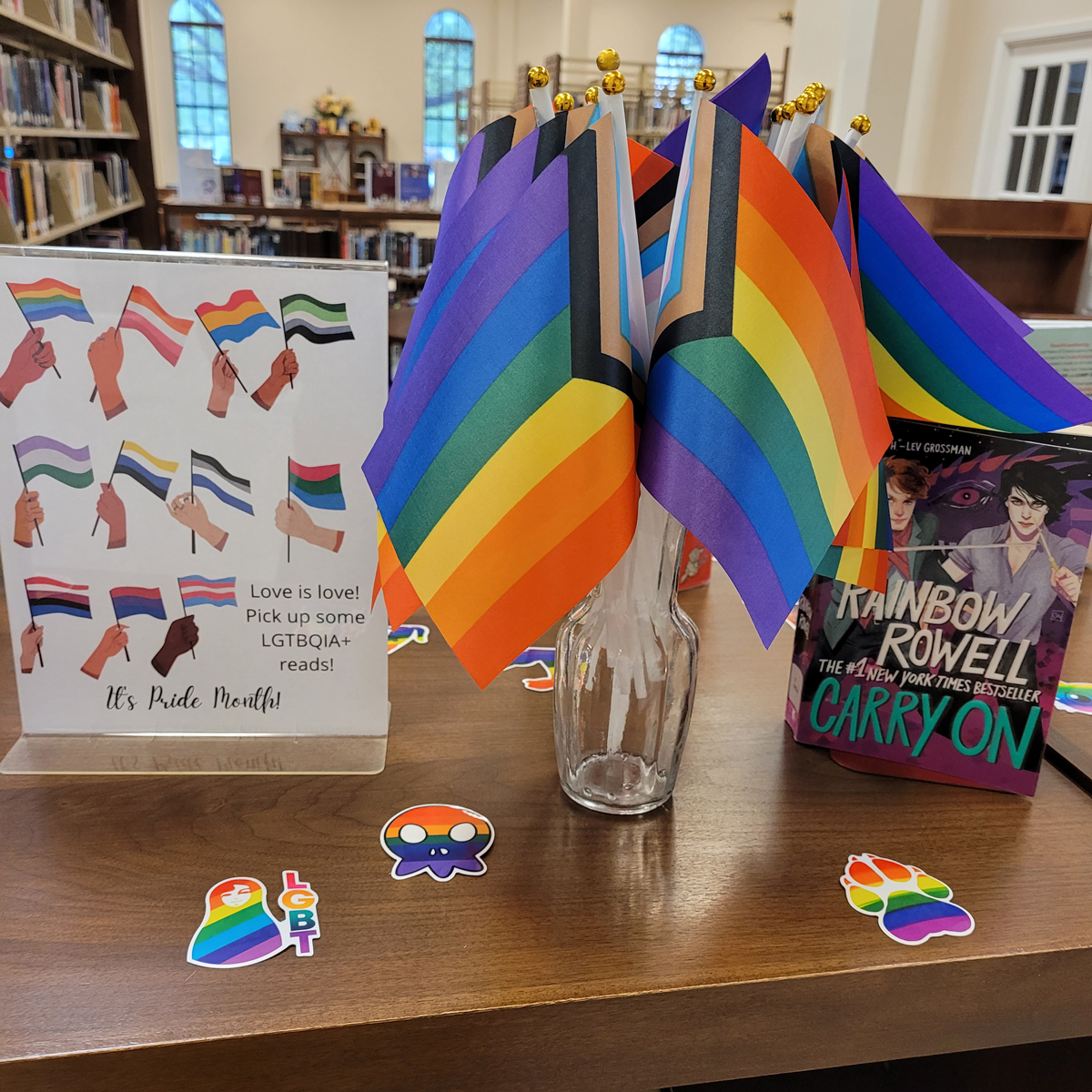

That desire to connect local people with information they need is a harbor in a storm during a time when libraries are under pressure to limit the books they offer, including LGBTQ+-related material. Evans’ willingness to push against that tide in northeast Mississippi soon attracted the attention of a filmmaker who grew up there in Clay County who is now supporting her efforts.

A Safe Space He Did Not Have

Award-winning filmmaker Michael Williams grew up and currently lives in West Point. After noticing Evans’ displays for Black History Month as well as Pride Month, which included books like “Felix Ever After,” “Mooncakes” and “The Poet X,” he decided to use his birthday, which falls in June during Pride month, as a way to support his home library and raise funds to expand its LGBTQ+ collections.

Williams recalls how a lack of representation led to his own feelings of shame and isolation growing up as a gay man in rural Mississippi. “All I saw was trashy reality TV shows showing a very small part of what the (LGBTQ+) community was like, and hearing the conservative religious right. It wasn’t until college when I starting meeting gay people that I started to have a positive view of gay people. It took that long,” Williams says now.

The filmmaker now understands how harmful that experience was during his childhood, despite staying active in Boy Scouts, church youth group and the West Point High School band. “There was always this kind of depressive cloud,” he says.

“I see how much I was masking, policing my inner voice and really suppressing my personality. I couldn’t even tell my friends, I had no one to talk to because I had such a shameful view. There was no positivity in all that.”

That experience made the filmmaker realize how, through this simple fundraiser, he could contribute to a safe space that he did not have, where young people can find themselves in a positive light. “With books, no matter if you are an ally or someone in the LGBTQ+ alphabet, there’s a book for you, and when you see positive, affirming stories, it gives power, gives knowledge and encouragement to be who you are,” Williams says.

‘Not Just the Majority View’

Jayme Evans strongly believes in inclusivity, which is why the inclusive displays are so important to her. “Everyone should be able to pick up a book and find themselves in the middle of it,” she says. “It makes me feel better when someone takes the time to write a book that has an African American woman as a main character. I want everyone to be able to walk into the library and find a book like that.”

But expanding a library collection requires funds. “Public libraries like the Bryan Public Library in West Point aren’t federally funded,” Evans says.

Community support is important because limited budgets make buying books a difficult decision. “Fundraisers help us make better choices so that we don’t have to limit the books we pick,” Evans adds.

A diverse collection of books also has constitutional implications for the Bryan Public Library, which several city and county governments fund. Kevin Goldberg, First Amendment specialist at the nonprofit Freedom Forum in Washington, D.C., reminds us that “the First Amendment stands for the idea that a community should be open to discourse and additional viewpoints.”

When a publicly funded library like Bryan decides to build a collection, the First Amendment officially prohibits bans in the decision-making process. This is how libraries get a “broad, diverse collection of books that not only reflects and broadens the community but also broadens the community viewpoint—not just the majority view,” Goldberg says in a telephone interview.

Under the First Amendment, everybody gets to participate, be heard and be acknowledged. The First Amendment means that “not only are we strong enough to be exposed to ideas we may not want to hear, but we need to,” he adds. This “marketplace of ideas” gives individuals the ability to inform themselves and change their minds if they choose.

Goldberg says librarians like Evans are significant for other reasons: “This is their career and their expertise. This is not someone from D.C. telling a small-town library how to build its collection. They are positioned to build the library, what the community tolerates and how the community should grow.”

Always a Banned Book on the Shelves

Williams shared his idea with Evans in early June 2022, who responded with excitement and then shared a long wish list of books the library hoped to purchase, including “A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo,” “How to Become a Planet” and volumes two to four of “Heartstopper.” Williams created a Google form, offering to send a small pride flag (or stickers) to anyone who donated at least $1. He then posted the form on Facebook, which was then shared on the library’s page, as well as an unofficial West Point community page.

The filmmaker collected most funds via Venmo, instead of using a fundraising platform, to avoid delays in getting funds to the library while also making it easier for him to collect information for mailing flags and stickers. Once the fundraiser ended, he provided the donations to the library in a single check. He covered all the expenses for the flags, stickers and mailing.

“It was overwhelmingly positive,” Evans says. “There was some negative feedback on social media, but we chose not to focus on that.” She noted that one out-of-state patron shipped 13 books to support the effort.

The library does routinely have folks who question its books, the librarian acknowledges, usually based on the title of the book or in response to what is in the news. But, it is not always a complaint. “When a Tennessee school board banned ‘Maus,’ we also had people calling who said ‘I have to read it because it’s banned,’” Evans says, laughing.

Regardless, the controversy doesn’t seem to faze the librarian, who believes that a library should always have a banned book on its shelves.

West Point resident and mental-health professional Brandi Cantrelle, who donated to the fundraiser, thought it greatly contributed “to the visibility of the LGBTQ community, especially in a town where they face a lot of homophobia.”

Although Cantrelle received negative responses on social media, “I did find out more people were in support of it than I realized,” she says. “I think there’s a lot more (support), but it’s too easy to pay attention to the loud, terrible voices. It’s important for folks in favor of something like this to be a little louder.”

Cantrelle adds that “the ugly voices are just loud and hateful, but that’s not the heart of the community.”

The fundraiser ultimately raised $1,760, which will allow for the purchase of as many as 150 books. For a library that Evans says “offers the community many functions, considering how many people don’t have access to computers, WiFi or books,” this is a large amount of money.

Evans hopes this will spark other ideas, once folks realize the different ways they can support the community. “We’re at the heart of the town, so it’s hard to imagine not having a place to get the books I want. Everyone should be able to walk through the doors and find something they like,” she said.

Editor’s Note: Michael Williams served as director of photography in January 2019 on a short film, which this article’s author John W. Bateman wrote and directed. Bateman’s novel is also included in the Bryan Public Library’s expanded LGBTQ+ collection.