The Mississippi Gulf Coast is in deep mourning after the passing of Dr. Gilbert Mason Jr. on Wednesday, May 18, 2022. I will never forget the legacy that he and his father Dr. Gilbert Mason Sr. left behind. Both men were instrumental in my family’s life and in shaping Mississippi’s civil rights history.

Gilbert Mason Sr. and his family moved from Jackson, Miss., to Biloxi in 1955 in the increasingly violent aftermath of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling requiring public-school integration. He and his wife, Natalie Lorraine Hamlar Mason, were both fresh out of college and looking to start a family closer to home. She is still revered as one of the “Mothers of Civil Rights in Mississippi.”

Biloxi was a segregated community known for its pristine beaches and “family friendly” environment. But the 26-mile stretch of Highway 90 soon would become the scene of Bloody Sunday, one of the most violent acts of race violence in America.

Mason Sr. was a phenomenal physician who loved the citizens of East Biloxi. He organized with Medgar Evers and helped lead the wade-in demonstrations to protest segregated Gulf Coast beaches. Black residents who paid ad valorem taxes to the City of Biloxi to fund the sea wall for the beach were excluded from enjoying the same amenities as white taxpayers. Mason Sr. felt the impact of segregated schools and unequal public accommodations on his family and the Black community in East Biloxi.

Whenever Mason Sr. took his family out to the beach, Mason Jr. was always by his father’s side. He noticed he and his wife could not take his young son to the white section of the Gulf coastline. He knew federal taxpayer money had funded the beach’s construction and maintenance, and that the entire body of the public should be able to use any part of it.

Mason Jr. had a photographic memory. “The individuals that owned property north of Highway 90 assumed erroneously that they owned property across the highway to the shoreline, but they didn’t,” he told Christopher Leach in an interview with brproud.com.

Mason Jr. Integrated Biloxi’s Separate School District

Mason Jr. was only 5 years old when he attended the first of several wade-in protests in Biloxi. My father Le’Roy Carney was just 10 years old when a white mob of anti-Black protesters brutally beat him and others during the “Bloody Sunday” beach wade-in in the 1960s. My father and Mason Jr. both experienced race violence as members of the Youth NAACP.

As a child, I was angry as I sat on the brown leather sectional in the living room, listening to my father. He gave harrowing accounts of law-enforcement officers sitting back as angry mobs beat and maimed innocent women and children.

Mason Jr. and the Youth NAACP were critical in youth outreach and organizing efforts that led to the desegregation of Mississippi’s beaches in 1968. On Sept. 2, 1965, he and the late Biloxi attorney Curtis Hayes were one of the first Black students to attend Biloxi Public School. The decision came after Mason Jr. was named in a discrimination lawsuit his father filed against the Biloxi Municipal Seperate School District. It was the first school district to integrate classrooms in Mississippi. In 1964, the local Daily Herald warned white Biloxians about the desegregation of Biloxi’s schools with this headline: “Biloxi School Mix Plan Is Submitted.”

Mason Jr. was just as passionate about fighting to advance equality for the Black community as his father. His family and friends urged him to graduate from the all-Black Nichols High School, but he attended Biloxi High School instead. It was a choice that changed the trajectory of Jim Crow laws in Mississippi.

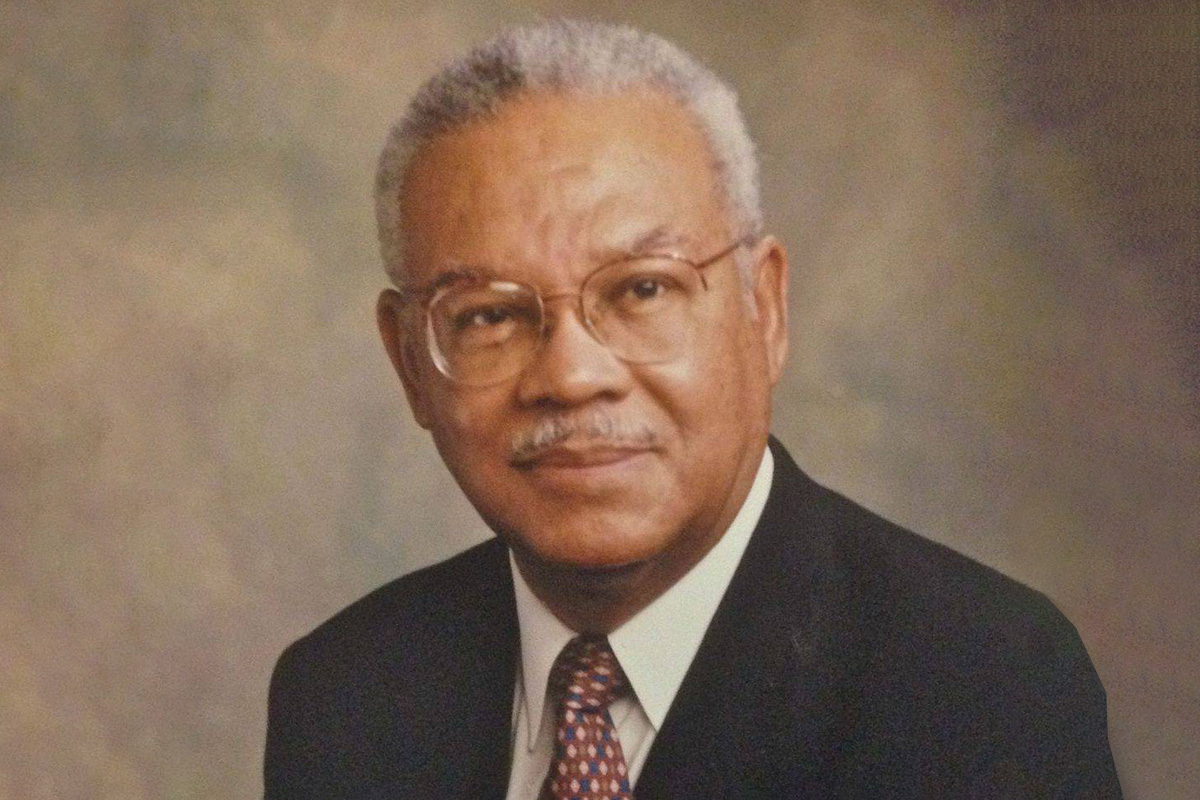

A Majestic Figure

Gilbert Jr. graduated with honors from Biloxi High School in 1964 and went on to practice medicine in underserved communities in New Orleans. He came back to Biloxi after his father fell ill. He always called on members of the East Biloxi community to help organize the annual wade-in ceremonies.

I talked with Mason Jr. during a wade-in ceremony in 2020 to commemorate the 60-year anniversary of Bloody Sunday and to pay homage to Mason Sr., my father and those who risked their lives on that horrifying day. My father is one of the last survivors of the Bloody Sunday wade-in attack.

Mason Jr. was a majestic figure who commanded the attention of everyone he met. He and my father laughed and talked about how far the country has progressed after everything they sacrificed. They remembered the tragic death of George Floyd and the impact it had on the Black community. Both agreed that we still have a long way to go. It was truly a testament for me to see. Lawmakers, businesses leaders and community organizers were working together during the ceremony to contribute food and refreshments to everyone in attendance.

Dr. Mason’s Thoughts On Reparations

Community organizer John Kemp of YO Gulf Coast and former Biloxi Fire Chief Joe Boney agreed to shut down east and westbound traffic on Highway 90 in Biloxi to allow our families an opportunity to cross over to the sandy beaches of the Gulf Coast to honor the legacy of Dr. Gilbert Mason Sr. and remember the history of Bloody Sunday.

I asked Mason Jr. about his thoughts on reparations for American descendants of slavery in the U.S. He lifted his eyes as he sat up holding a smooth, black walking stick. “I support what you all are doing. I’d love to see it in my lifetime,” he told me. His words reflected the struggles and triumphs that American descendants of slavery faced during Jim Crow and the inequality that we experience today.

As we honor Juneteenth, I vow to accept those challenges and continue the legacy that Dr. Gilbert Mason Jr. and my ancestors left for me.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.