I was taking an American History class at my high school in southeast Alabama, where my family had relocated from here in Neshoba County in 1995. We were on the subject of the Civil Rights Movement, and I still remember that sentence in my textbook: “Three civil rights workers disappeared in Mississippi.”

”Huh, I wonder where?” I remember thinking to myself. The textbook didn’t elaborate further, only to note that this event led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Still, I became curious.

An Alabama history course requirement covered in detail some of the familiar events there such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Selma-to-Montgomery march. I felt lucky to live in an area where I could visit the city where this history occurred and, it turns out, the same Highway 80 that connects Selma to Montgomery is on the same route that my Alabama family takes to get home to east central Mississippi, just in the opposite direction.

Despite Highway 80 making a bypass route around Selma, we’ve made it a point a few times to take the downtown route in order to see for ourselves the infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge, where Bloody Sunday occurred in March 1965.

Plus, the late Rep. John Lewis was from the town, Troy, where I grew up. Troy University recently renamed a building after him after his death in 2020.

But I didn’t learn about the Choctaw’s place in Neshoba County civil-rights history until much later.

A Shock in Mississippi

I’ve alluded in past columns in the Mississippi Free Press that I spent summers visiting my grandma and other family members back in Neshoba County until the school semester started again for the fall, and we then returned to Alabama.

This one particular summer in 2000 I believe, I happened to read the local paper’s annual announcement and related historical accounts of what happened in Philadelphia, Miss., in 1964. I was floored to find out that the “three civil rights workers (that) disappeared in Mississippi” sentence I read in my history textbook in Alabama had occurred right here in my hometown! I became incensed and was suddenly thirsty to find out more.

I could not believe that, at that point in time, it was just a generation before that all of these events occurred in our county, and not just that. The church local white Klansmen burned was just down the road from my home in the Choctaw community of Bogue Chitto in the county east of Philadelphia. All of my childhood, I had passed the road that led to that church millions of times and never knew of its existence or its significant place in history.

In addition to my awakening, the fictionalized movie that was based on the series of events in Neshoba County included two of our own tribal members as extras to represent the real-life Choctaw man who discovered the three men’s burned station wagon off Highway 21 just north of the Bogue Chitto Community.

Barry Davis Jim Sr. has a credit in the movie as simply “Choctaw Man.” It is his son, Barry “Movie Star” Jim Jr., who can be seen in the background as a little boy running around. Barry Davis Jim Sr. was an announcer at times for stickball games during the Choctaw Fair, but sadly passed away in June 2014.

The cover art for the VHS version of “Mississippi Burning” had been in my living room since I could remember. It might have been playing on our TV at one time, but I don’t recollect because I didn’t pay attention as a child. I just remember seeing that movie along with “Ghosts of Mississippi” along with other native titles like “Dances with Wolves” in my dad’s VHS collection.

After learning about the history of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, I had to watch the movie for the first time at 16 years old. I watched it along with some friends of mine at a house in Alabama, the whole time mentioning that the dramatized events occurred in my hometown.

I explained that “Jesup County” is actually Neshoba County, and Philadelphia does not look like the dusty town portrayed in the film. Did it look like that in 1964? I don’t know.

Segregation Kept Choctaws Uneducated

In addition to the movie, I discovered the more factual book “Witness in Philadelphia,” written by white Philadelphia native Florence Mars. I went to the local library and checked out the only copy that was available. I haven’t read the book in 20 years, but what I remember from my reading was the scene at a local store her family owned and this particular Choctaw family who came in and bought items one by one.

Mars wrote that she was curious about their method of careful shopping and spending, and after talking about this book to my mother, she nonchalantly quipped that those tribal members likely didn’t know how to count money. True, education was denied to Choctaw tribal members due to segregation during Jim Crow times, and Choctaw Central High School didn’t open until 1963. It would take a whole generation later until the education levels of the tribe would finally approach those of our white and Black neighbors. Just this year, the tribe celebrated our first-ever tribal member to obtain a medical degree, Dr. Christina Wallace.

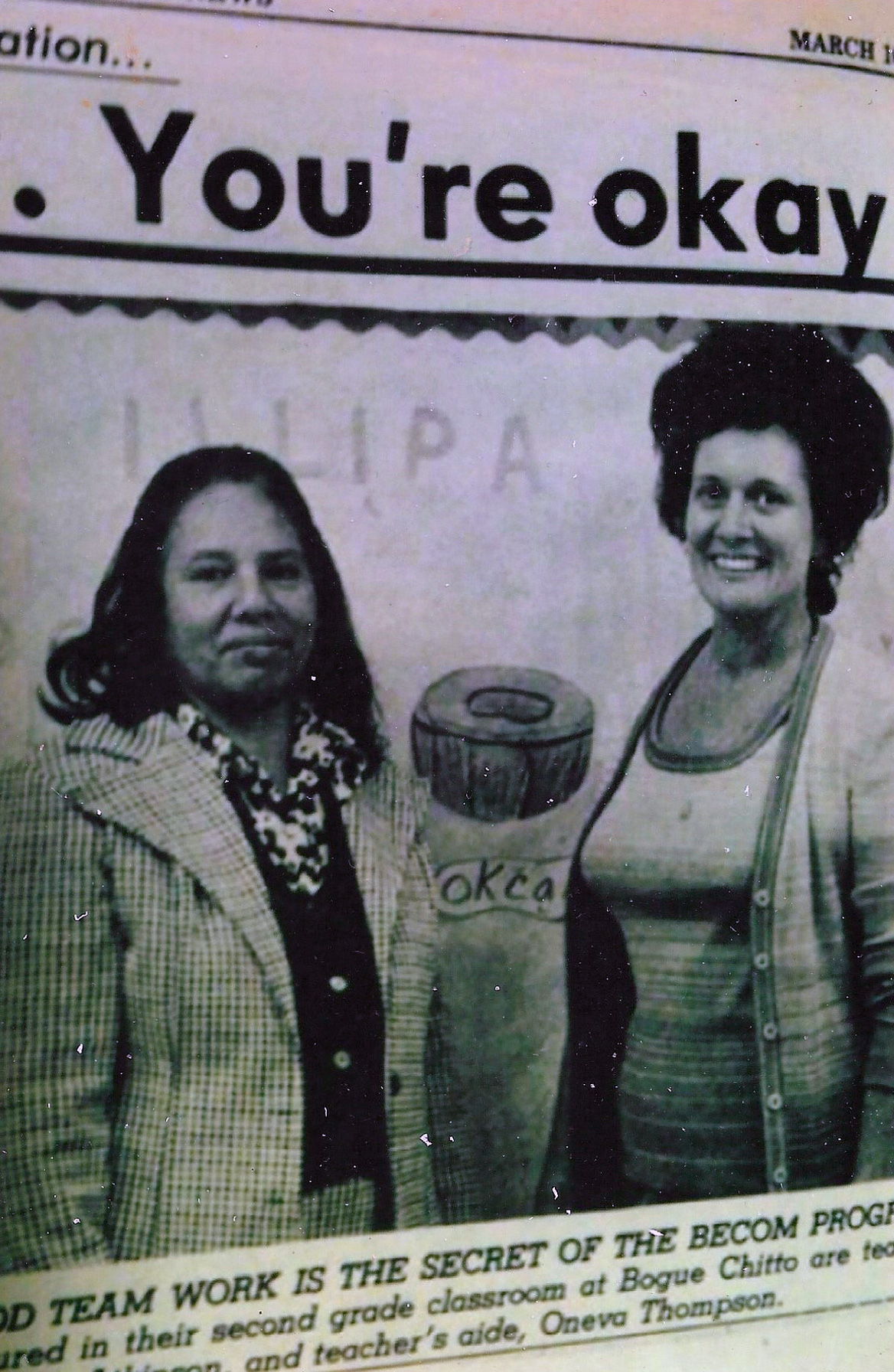

Those in my grandmother’s generation, if they so desired to obtain an education, had to leave Mississippi to attend BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) boarding schools. My maternal grandmother, Oneva Thompson, did just that. She attended high school at the Cherokee reservation in North Carolina and returned home to Mississippi to become a teacher’s aide at what was then Bogue Chitto Day School in our home community.

I also recollect asking my aunt about that time period. She remembers being a little girl in the 1960s and looking out through the screen door and seeing what could have been U.S. Marines or Army members combing the swamps near Bogue Chitto, either before or after the burned station wagon was found on June 23, 1964, two days after the three civil rights workers disappeared.

Gaining this knowledge, and realizing there was a Choctaw connection to this historical story that was not as well known, I have been on a personal conquest ever since to find the identity of this person (or persons) to see if I possibly could be related.

It is now 2022, and I still don’t know the identity of this person, as many MIBURN case files from the FBI are heavily redacted. My search isn’t helped by the fact that many people did not discuss it, and apparently even history books just brushed right past the Choctaw role in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

With the current state of affairs in America regarding race, politics and American history curriculum, it is imperative that more history is taught, not less. To be sure, not all history is pleasant to study and face, but is definitely necessary in order to try to heal from generational trauma and look forward to a better future, for all of us.

The story of my home county is more than Black and white.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.