A preset alarm blared at 7 a.m., leading Duvalier Malone to reluctantly open his eyes. It was morning again in Jackson, Miss., meaning another day of work, class, WIN job center.

“I did everything right,” he thought to himself. “It wasn’t supposed to be this way.” He was supposed to be in law school, not working as a department manager at Dillard’s. This job had nothing to do with the political-science degree he had earned in May from Alcorn State University.

It was August 2008, and Malone’s future was just as uncertain as Mississippi’s fall weather. But that didn’t stop him from getting out of bed and completing his morning routine before sliding into his pressed Dillard’s uniform, grabbing his keys and running out the door.

Twenty-three years old at the time, Malone was focused on furthering his education and forging a political career. He had decided on a political science master’s program at Jackson State University and was adamant about making this uncomfortable retail interlude just a step toward success. He fought through moments of doubt, shame and disappointment on his morning commutes, making sure Hallelujah FM kept him inspired every mile.

At 8 a.m. sharp, Malone walked into the Jackson WIN Job Center off Interstate 55 North, filled out as many state job applications as possible, then left at 8:30 a.m., just in time to make his shift 15 minutes early. After work, he went to coworker Stephanie’s place to hang out. There, he got a text from Brian, another friend and coworker, saying he was coming over with a friend.

Moments later, Brian and his guest arrived. Malone realized that this was the same friend that came up to Dillard’s to visit Brian from time to time. Brian then formerly introduced him to Adrian Mayse, one of his good friends from the University of Mississippi.

Malone had always been the flashy, go-getter, social butterfly, extroverted type. So of course, he introduced himself with a smile. But Mayse was laid-back, calm and cool, with a quiet temperament and genuine spirit. Malone could tell he was shy.

They only had time for cordial introductions at Stephanie’s that night. It wasn’t until Valentine’s Day 2009 when Malone mustered up the courage to ask their mutual friend Brian for Mayse’s phone number.

Malone only planned to be in Jackson temporarily for graduate school since he really wanted to move to Washington, D.C., and get into public work. “I’ve always wanted to have a connection in a netting to Mississippi, but I never saw myself in Jackson in my early 20s. I didn’t want to make too many roots or too many ties, and I ended up doing just that. I ended up meeting somebody.”

It had to be God’s plan to meet Mayse, Malone says, because he wasn’t where he wanted to be academically, financially, and honestly he wasn’t sure how he wanted to identify sexually. Yet here was Adrian Mayse—mature, already connected socially in the capital city with a career and just comfortable in his own existence.

“It was something about Adrian at my friend’s house,” Malone confessed. “The reason why I got the guts, I don’t even know. I honestly think it was just divine intervention because normally, especially at the place that I was in at that time, I would have never went and, like, asked for a number.”

Malone knows that Mayse entered his life right when he needed him. The start of this relationship helped to set the foundation for Malone’s activism in the Magnolia State, leading him to establish more roots to work on various social- and economic-justice issues. This relationship cultivated a safe environment for Malone to spread his wings and personally develop as he pursued his life-long dreams.

From Fayette to Byhalia: The Love Story’s Origin

Both Duvalier Malone and Dr. Adrian Mayse are Mississippi bred and raised. Malone hails from Fayette in southwest Mississippi whereas Mayse grew up in Victoria, a community in the Byhalia area, which is further north near Memphis, Tenn.

After a few setbacks following his graduation from Alcorn, Malone set his sights on Jackson State University, starting in the public policy and administration program and eventually transferring to JSU’s political-science program where he earned his master’s degree. By 2009, Malone went from working at Dillard’s as a department manager during graduate school to working with the Young Democrats of Mississippi and America and traveling the country during Obama’s presidency.

Malone started working for Veterans Affairs in August 2009 and continued to work his way up from a veteran service representative to a Veterans Administration program analyst in D.C. After serving as a special assistant for Secretary David Shulkin and then Secretary Robert McDonald in 2017 to 2018, he became a director of correspondence for the veterans health administration. Today, Malone is the associate director of the electronic health records modernization office.

Mayse graduated from Byhalia High School and then enrolled at the University of Mississippi, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in finance after three years. In January 2006, Mayse left for Jackson to move in with their mutual friend Brian. By fall 2006, Mayse started a master’s program at Jackson State University while working at the Mississippi Department of Revenue for three years.

Duvalier and Mayse were officially dating by March 2009. But soon afterward, Mayse decided to move back to Victoria, about three hours from the capital city, to stay with his grandmother, who had lost her husband a few years prior. This was the first time Duvalier and Mayse had to love from a distance, which they did for over a year.

Mayse moved back to Jackson in 2010 to start his doctorate journey at JSU, but moved again in 2013 for a job in Murfreesboro, Tenn. During his time in Tennessee, Malone also took a job in the District of Columbia, putting the couple even further apart. They agreed that effective communication, sacrifice, intentionality and weekly travel dates helped keep their relationship strong during this period.

“It’s been very interesting,” Mayse reflected, laughingly. “The evolution of our relationship, the sacrifices we both had to make, have made to be together and stay together—it’s been 13 years.”

“We spent a lot of money on flights,” Malone explained. “Adrian had a rule when I was in D.C.; he pretty much tried to come every weekend.” Two years later, Mayse also moved to D.C., bringing them together in the same place at last. Now, Mayse is a certified public accountant as well as an associate professor and chair of the Department of Accounting at Howard University.

‘We Want It to Be About Us’

Intentionality is a main theme to this love story—it’s pertinent to be equally yoked in values and maintain an authentic commitment to one another by making moves to center each other’s career goals and passions. Both Malone and Mayse intentionally dated each other to build a life together from the very beginning in 2009, and they decided to have a commitment ceremony in 2011 with some of Mayse’s close friends.

“Of course it was before (gay marriage) was legal,” Mayse explained. Once it was legal, they went back and forth on whether they should get married and questioned their own motives: Should we do it now just because it’s legal, or are we really ready for this next level of commitment?

This was before Malone came out publicly, so the timing of their declared union had to be right. Mayse knew he wanted to marry Malone and felt like they reached this place of bliss. “I just feel like we’re in this place, you know? Why wait? There’s no perfect time,” he said.

After a couple months of planning and talking the proposal over with his friends, Mayse felt encouraged and went right out to get the ring he knew Malone wanted. Every other detail organically fell into place.

“I proposed for the second time in December 2019, and he was not expecting it,” Dr. Mayse said, chuckling at the memory. They decided to ring in the new year dressed up for tea time at a posh, local tea joint that has since closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic—an intimate party of five including Malone’s baby sister and Mayse’s unsuspecting best friend. Mayse knew he wanted to propose that day, so he kept the ring on him, but he had no idea exactly how and when he would pop the question.

Duvalier was definitely surprised. He just thought they were getting dressed up in debonair suits and classy fedoras for tea hours with their favorite people to bring in the new year together. Instead, the day ushered in a new beginning for them both.

“No matter what people say, being in a partnership is one thing, but the idea of someone wanting to be legally married also helps validate your relationship, right? It does put a different type of seal on it,” Duvalier stated.

The two originally planned to wed in December 2020, but COVID-19 put those plans on hold—through 2020 and the bulk of 2021. While trying to figure out the perfect date to get married, they realized, “We want it to be about us.”

“So it was just the two of us—our officiant therapist, our dog and, yo, that was it. We got married Dec. 31, 2021,” Mayse concluded.

The Elephant in the Room: LGBTQ Advocacy

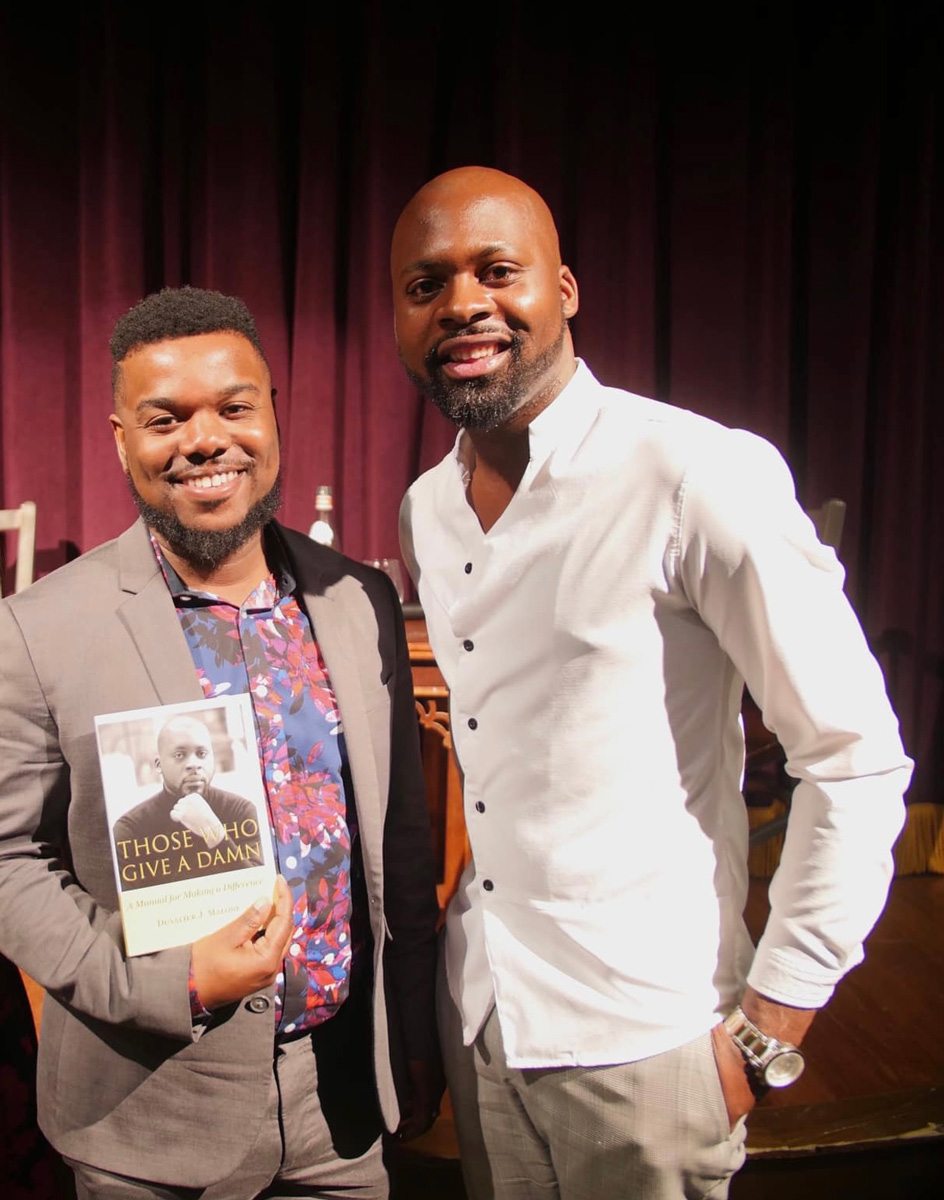

“My very first column was (me) coming out as a Black, gay man from Mississippi,” Duvalier Malone, now 36, stated, reflecting back on the article published April 11, 2016, in the Jackson Free Press.

Malone remembers vividly where he was in life that week—in his career, in establishing his own identity and walking in it, and in love. He had been dating Adrian Mayse, 37, for seven years at that point, had built a solid political foundation via his seven-year tenure at the Veterans Affairs office, including his activism and political commentary on radio stations, and he had just been recognized for Mississippi Business Journal’s Best 50 Under 40 Award.

Everything seemed to be falling right into place, and both of their futures looked bright, until an email from a young, Black, gay man appeared in Malone’s inbox. The young man wrote how much of a fan he and his mom were of Malone’s budding career and political commentary; they were both proud of all the good things Malone was doing for Mississippi.

Then the young man said, “But my mom hates me.”

“I think you may be gay,” the young man wrote. “You may have a partner that I see in photos, but I’m not sure.”

He admitted to Malone that he had been contemplating suicide, and Malone suddenly felt the weight of this email transfer to his own shoulders. Conflicting, yet emotionally high things were happening simultaneously: the rising trajectory in his political career, his working side-by-side with the love of his life as he accepted this prestigious award, and the passing of a bill that discriminates against his own community.

“I didn’t think I was actually living in my authentic truth at the moment because I had not been an advocate,” Malone said. “I spoke about everything in Mississippi but LGBTQ rights.”

After receiving that email, Malone felt compelled to use his political position and public power to advocate for the LGBTQ community in hopes of moving the needle of progress forward in his home state, particularly given the large platform he had within Black communities in Mississippi.

Former Gov. Phil Bryant had signed HB 1523, the “Mississippi Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act,” into law seven days before the Jackson Free Press published Malone’s column. HB 1523 creates government protections for “sincerely held” religious beliefs or moral convictions for people, religious organizations and private associations—public and private business owners can legally refuse services to LGBTQ people based on their own religious beliefs. These “sincerely held” religious tenets determine that housing, employment and adoption decisions could be made based on religious beliefs.

Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Hinds County, authored the bill, and he called the high court’s legalization of marriage equality “in direct conflict with God’s design for marriage as set forth in the Bible,” the Washington Post reported. HB 1523 was expected to take effect on July 1, 2016, but U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves issued an injunction blocking enforcement of the law on June 30, 2016. Then a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals lifted the injunction on procedural grounds, ruling that since the plaintiffs were not personally harmed due to the legislation, they did not have a stand to challenge it. On June 22, 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take the appeal, thus allowing the law to stand today.

‘How We Show Up In The World Matters’

Mayse just wanted to know if Malone was completely sure about being so transparent in a polarized climate like Mississippi as an outspoken and politically active gay, Black man. Mayse never had a grand coming-out, technically, saying that he had always been out in some sense.

“I was just making sure that he was ready because I knew the potential impact,” Mayse continued. He wanted to make sure Malone was mentally ready to walk in his truth, knowing that many would pull away or no longer support him just because he came out as gay.

“Are you mentally prepared for what you may gain, but also for what you may lose?” Mayse asked. He was initially shocked as he is usually Malone’s sound board before he writes anything or makes any risky decisions. But this time, he first read the article on a plane ride from Washington, D.C., to Mississippi with Malone, after it was published.

“Adrian is a natural protector,” Malone explained. “When I bring ideas to him, they kind of go through a murder-board process in the house,” he said as they both laugh. “So I was like, I don’t have time for a murder-board process. This is urgent.”

“He’s a very level-headed, focused individual, so I’m always proud when he does what he puts his mind to,” Mayse said emphatically. “I knew when I read it, it was confirmation that OK, this is the time, and this is how he wants to do it.”

Malone remembers the losses—contracts and job opportunities he lost after the article went live—but he decided to focus on his wins and the overwhelming support from his own LGBTQ community.

The young man eventually wrote Malone back after the column was published, and Malone became his mentor. This new-found relationship inspired Malone to give away some scholarships the following year. Hearing back from this young man was a relief for Malone because otherwise, he would’ve never known what happened.

“It just really made me very conscious that words matter, what we say matters, how we show up in the world matters,” Malone said.

Malone knows firsthand how rare it is for the young LGBTQ community to see proper representation of themselves in Mississippi. “I wanted them to be able to see an example of Adrian and (me)—not as perfect people, but to understand the love we have for one another,” he said. Malone wants other young Mississippians like them both to be free to live and love openly.

Mayse does an extremely good job of holding him accountable, including for his narrow focus, Malone said.

“That moment changed my life, and it helped me grow up as a public servant,” Malone stated. “I was bold before coming out, but I think I became even more bold. That was my very first column. I found my voice in that writing.”

Malone explained how finding his voice led to him working on the Mississippi Confederate flag issues and advocating for the reopening of the Emmett Till case with an organized “Demand Justice” rally at the Capitol.

Find Your Tribe, Then Live In Your Truth

As a Black, gay couple from Mississippi, both Malone and Mayse desire to encourage others like them to find their tribe—an outlet they can identify with that offers safety and trust for intimate, real conversations. Malone remembers the few supportive resources accessible to him 13 years ago and is proud to say that many more resources are available today.

“Start understanding that you are not alone, that there are other people out there like you,” Mayse said. “As far as love, it’s what you make of it.” He encourages everyone to realize that all relationships are unique and valid, and despite the differences, it’s still love.

“Be OK with accepting who you are early in life and stand in your truth no matter what,” Malone decreed. “Don’t spend your entire 20s running away, like I did, from your truth. I promise you, when you own it and live in it, you’re going to be able to do some amazing work. You’re going to be able to be really free and authentically creative because you are living in your truth.”

In love, Malone has learned that it is not so much about being individuals, but being on one accord as a unit. He says that some days are better than others, and there will be challenges, but standing together helps to extinguish any outside forces that may come in to challenge your union.

“How do I keep us at that oneness? How do we get back to that oneness? How do we flow in that oneness because when you do, you’re not easily divided,” Malone advises.

“For every young, gay person out there, I just want them to understand and know that they matter and that they are important to society,” Malone states. “They have just as much to offer and their love stories should be just as elevated as other heterosexual love stories.”