“I am on a pilgrim of sorrow. Tossed in this wide world alone. I have no hope for tomorrow,” Fannie Lou Hamer sings. “I’m trying to make Heaven my home. Sometimes I’m both tossed and driven. Sometimes I know not where to roam. I’ve heard of a city called heaven. I started it to make it my home.”

Hamer’s powerful rendition of Mahalia Jackson’s “City Called Heaven” greeted guests who logged onto the “Finding Your Voice Though Fannie Lou Hamer” virtual panel on Feb. 15, 2022. The lyrics differ from the original, but the sentiment still rings true. The sorrow, raspiness and power in her vocals rival that of Black church choirs on a Sunday morning. Burdens are being laid bare to those who listen.

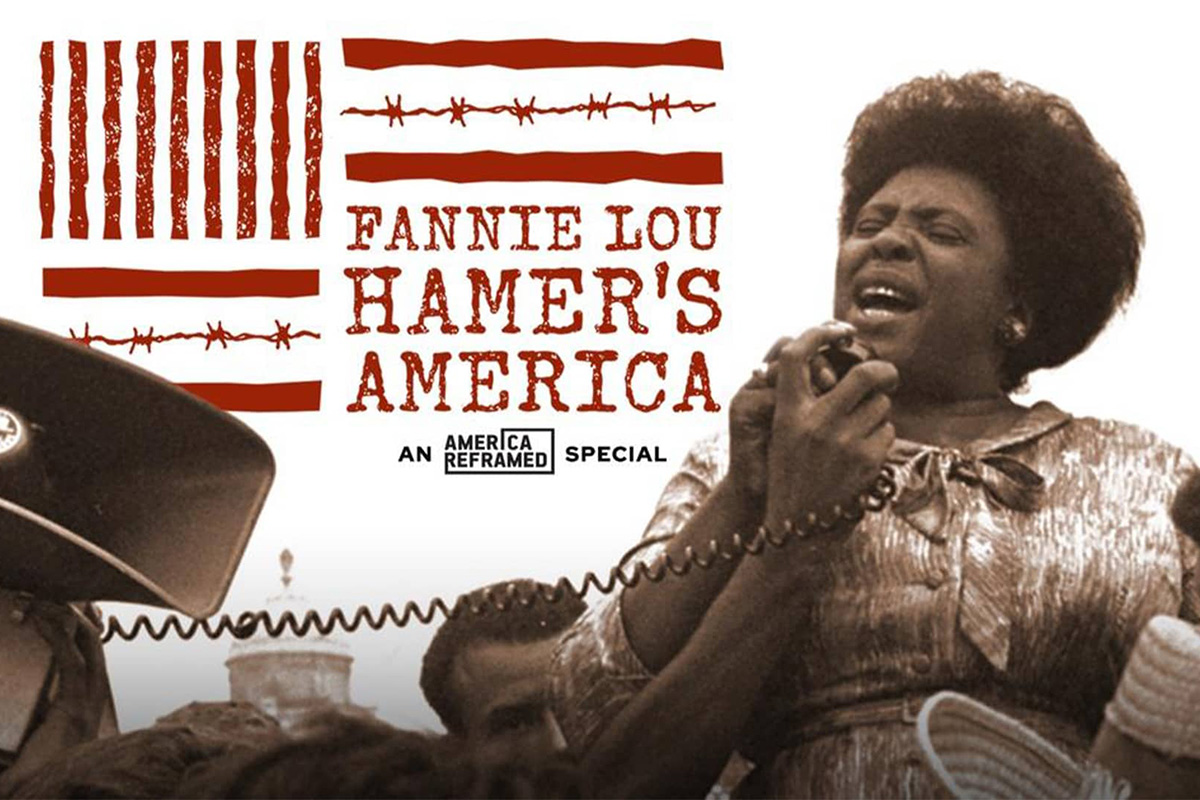

The speeches, songs and interviews of Fannie Lou Hamer are available for the world to witness in “Fannie Lou Hamer’s America,” a new documentary film that opened the 10th season of “America Reframed” on PBS on Feb. 22. The WORLD Channel also broadcast a premiere for the documentary on Feb. 24.

The Zoom panel brought together Hamer’s great niece Monica Land, documentary director and editor Joy Davenport, author and historian Keisha Blain, and actress and activist Aunjanue Ellis to discuss Hamer’s influence and legacy today.

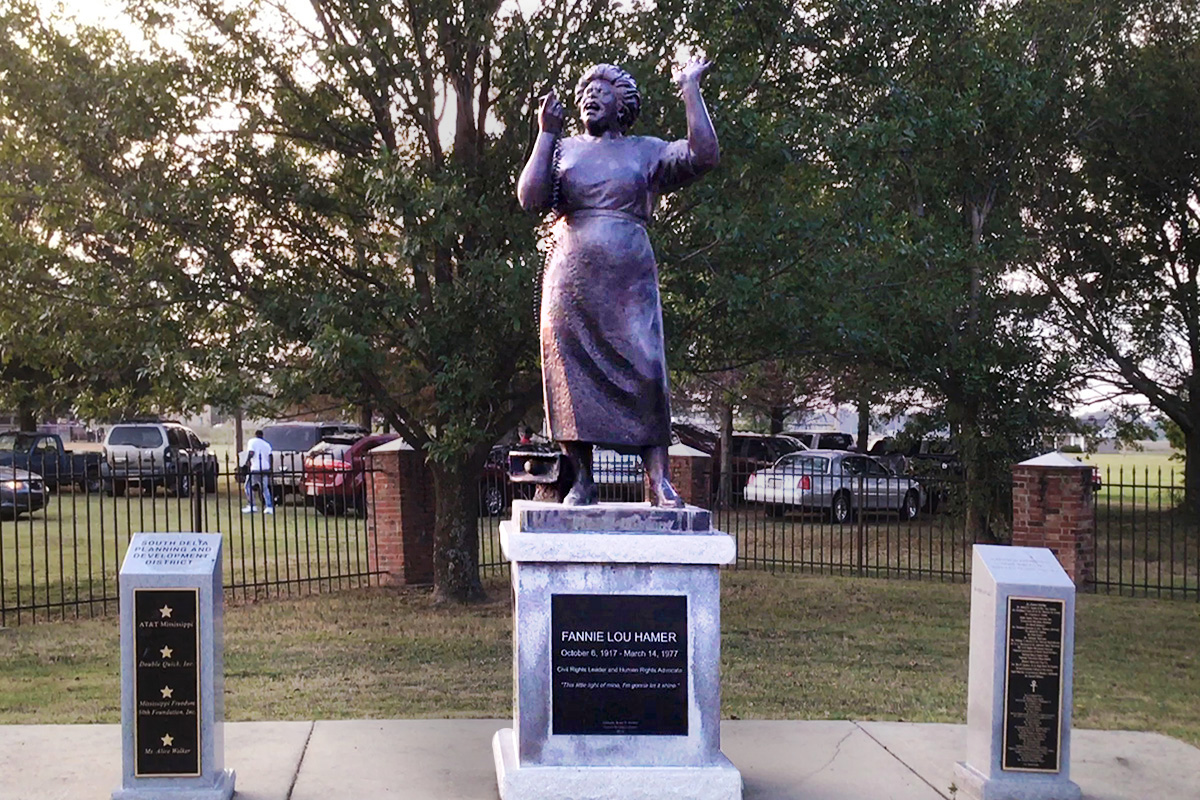

Born in Montgomery County, Fannie Lou Hamer created a name for herself as a civil-rights activist and co-founder of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party from the Delta. The youngest of 20 children, she began working in the fields when she was 6 years old, as her parents were sharecroppers.

Around age 12, she dropped out of school to work full-time and help her family. She continued to work as a sharecropper after her marriage to Perry “Pap” Hamer in 1944 and the couple toiled on B.D. Marlowe’s plantation in Sunflower County near Ruleville, also in the Delta, until 1962.

In summer 1962, Hamer attended a local Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee meeting encouraging Black people to vote, which led her to travel with 17 others on Aug. 31, 1962, to the Sunflower County courthouse in Indianola so she could join local advocates’ efforts to further this goal. They encountered resistance from local and state law enforcement, but only Hamer and one other person were allowed to fill out applications.

Registering to vote cost Hamer her job and home on the plantation. These setbacks solidified her resolve to help other African Americans obtain the right to vote. She became a community organizer for SNCC in 1962 and spearheaded voter-registration drives and relief efforts, although her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement often led to her being beaten, arrested and shot at.

In 1964, Hamer helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in opposition to her state’s all-white delegation and announced her bid for Congress. She lost the Democratic primary, but she brought national attention to the civil-rights struggle in Mississippi during a televised session at the convention.

Outside of voter registration, Hamer set up organizations to increase business opportunities for minorities and to provide childcare and other family services. In 1971, she helped establish the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Doctors diagnosed Hamer with breast cancer in 1976, but she continued to fight for civil rights nonetheless. On March 14 of the following year, she died from cancer in a hospital in Mound Bayou, Miss.

Monica Land, Hamer’s great niece, doesn’t have many memories of her aunt, because she was so young when Hamer passed away in 1977. However, Land said she hears stories from her family all the time, who speak of the civil-rights icon as someone who loved to laugh, joke and work extremely hard at whatever she did.

“The fact that she could still laugh the way she did is just tremendous,” Land said during the panel. “She loved to cook. She loved to eat. She was very hospitable. And so all of those things just contribute to my admiration of her as an extremely strong-willed person.”

Land said Hamer and her family sacrificed and gave so much as sharecroppers, yet they had so little, living in dire poverty Hamer’s whole life. In knowing the contribution Hamer made to society, however, Land wants to use this film as a vehicle to recognize and remember her great aunt.

“It’s hurtful almost to know that she made such tremendous strides for Black people, and then most people, most young people, don’t even know who she is,” Land reflected. “And so this was an effort to preserve her memory and to remind them that we have these freedoms because of people like Fannie Lou Hamer and others.”

‘Her Voice Is So Powerful’

An avid history enthusiast with an interest in film, Land came up with the idea for the documentary in 2005 and subsequently approached her cousin, Sulla Hamer, who is a feature-film producer, for advice. Unsure, Sulla introduced Land to filmmaker (and Mississippi Free Press advisory-board member) Keith Beauchamp, who passed on some knowledge on the field and directed her to Fannie Lou Hamer Professor of Rhetorical Studies Dr. Davis Houck of Florida State University. In turn, Houck guided Land to Megan Parker Brooks, a Fannie Lou Hamer historian. Finally, Beauchamp and Houck arranged for Land to meet Joy Davenport, who agreed to direct the documentary.

“It was just a coming together of the minds, and it was just the best team ever to get this project off the ground,” Land said. “That happened around 2007, and around 2016, we actively started working on getting grants to make this happen.”

When Davenport was working on her master’s thesis at Florida State, she originally planned to present an oral-history project about the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Midway through it, however, she decided to turn her thesis into a documentary, which Houck directed.

“I didn’t know how to make documentaries,” Davenport reflected during the panel. “I didn’t even know how to hold a camera, but I had a friend with a camera, and so we drove out to Mississippi and interviewed a bunch of folks.”

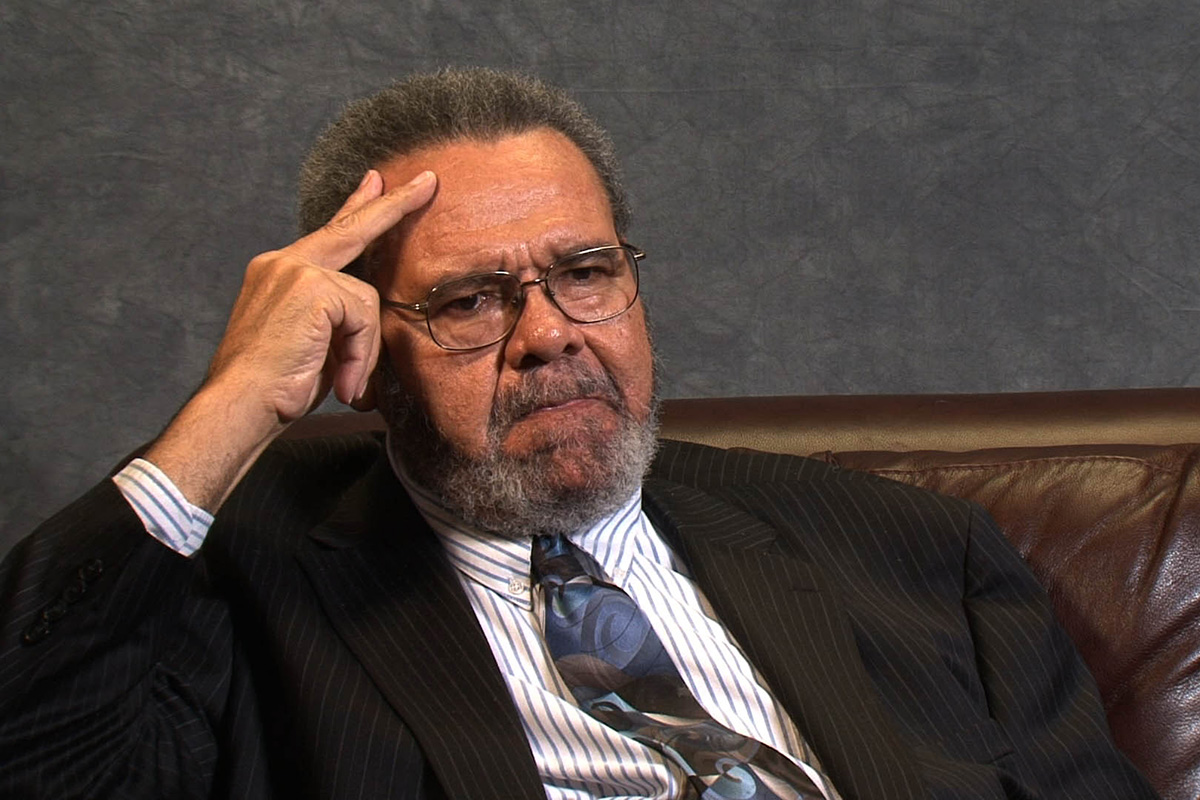

The project put her in contact with the now-deceased Lawrence Guyot, the original chairman for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. He became a mentor to Davenport, sending her books, articles and calling her to suggest notes, the director said.

“When I finished that project, he was very happy with the result and said, ‘Well, the next one’s gotta be about Mrs. Hamer,’” Davenport recalled. “And so that was for me the entry point into, ‘Yeah, the next movie I make is gonna be about Fannie Lou Hamer.’”

After meeting and discussing their ideas for “Fannie Lou Hamer’s America,” Land and Davenport agreed that the film needed to showcase the activist’s physical voice through her words, songs, speeches and interviews. This choice posed a unique challenge for making a feature film using only archival materials of Hamer speaking, Davenport said.

“For one thing, her voice is so powerful,” she elaborated. “It’s so unique, and it is impossible to listen to her speak about her experiences and deny the truth of what she’s talking about. Her speaking voice (and) her singing voice (are) just so stirring that to have somebody else translate that for you either through talking head interviews or narration would just remove you from that power.”

As white woman, Davenport questioned whether she had the right to direct the film, given a history in feminist movements of white women shamefully attempting to speak on behalf of Black Americans despite not sharing identical experiences.

“I’ve tried to quit a couple of times on Monica, but I felt like the only ethical way to do it considering my identity is to craft something that makes as much space as possible for her voice, a platform and a spotlight, and to remove the kind of maker from the equation as much as I could,” Davenport explained.

The film director also worked as a filmmaking instructor for the Sunflower County Film Academy in 2018, where students produced films about their lives in the Delta and connected their stories to Fannie Lou Hamer.

“That was one of my happiest thoughts because I remember how exciting it was ’cause it wasn’t that long ago that I learned how to use a camera and the kind of world that opens up,” Davenport said.

‘Articulating That Pain’

Actress Aunjanue Ellis didn’t learn of Fannie Lou Hamer during her 12 years in public school nor in her four years of undergraduate school, where she studied African American studies. She, like many Mississipians, learned of Hamer through the grapevine, in freedom-rights stories that made their way around the state, she explained during the panel.

“She is this incredible force of truth and wisdom and morality—and when I say morality I don’t mean morality in a trite sense of right and wrong—I mean morality in the larger sense of what it means to be a human being in this world,” Ellis said. “So I am slain every time I hear her speak, every time I read her words.”

The Oscar-nominated actress’ grandfather pastored Society Hill Baptist Church in McComb, Miss. In 1964, he opened his church to civil-rights workers so they could gather and hold meetings. As a result, proponents of civil rights bombed his church, and then local police arrested him for allegedly bombing his own church, Ellis recounted.

“The civil-rights incidents for McComb just in that year looks like (Leo) Tolstoy,” the Oscar-nominated actress said. “It’s that dense. And so we really didn’t talk about Mrs. Hamer in our home because I guess in the minds of my family, (she) wasn’t that remarkable because we had so many Fannie Lou Hamers around us.”

The actress had the opportunity to star in a short film where she played Fannie Lou Hamer and recited her infamous testimony at the National Democratic Convention Credentials Committee on Aug. 22, 1964. Ellis laughingly said she did her best in portraying the iconic activist but that she has a lot more work to do.

“What Mrs. Hamer did with her experience is that she expanded that pain and articulated that pain in a way that other people who went through certain things that she went through did not,” Ellis said.

Historian and writer Dr. Keisha Blain, who wrote “Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message To America,” said many factors play into how long it takes many people to learn of Fannie Lou Hamer’s life story and achievements.

One of those factors is that historical narratives about the Civil Rights Movement, even to this day, are often male-dominated, Blain explained. She exemplified this pattern by pointing toward the July 2021 passing of activist Gloria Richardson, when The Hill ran a story about her death with a photo of Martin Lurther King Jr. (As of today, no photo accompanies the article, and the only photo of her is included in a tweet embedded in the article.)

“Of course, so many people were outraged about this because it would not have been too difficult to find a photo of Gloria Richardson,” Blain expressed. “When I saw that, it took me right back to sitting in classrooms; it took me right back to reading so many books about the Civil Rights Movement and just seeing the way that women, though they were vital to the movement, were often marginalized in these stories.”

The historian said it is also important to note that Hamer did not fit the mold of what many people thought civil-rights activists should look and sound like.

“Fannie Lou Hamer was someone who had a sixth-grade education. She simply told you what was on her mind. She did not subscribe to respectability politics, which of course has shaped and framed Black history to this current day,” Blain said.

“I think when you look at that aspect of her life, the fact that she was a disabled Black woman, a working, poor Black woman, so many factors come into play that I think many writers and historians did not pay attention.”

At a Dec. 16, 2021 meeting, members for the Mississippi Board of Education approved initial steps in changing the social-studies standards within the state’s educational system. In the 309-page document, specific names or descriptions have been removed or changed with language and terms that are more generalized, Mississippi Today reported in January. The changes met some backlash, which caused the board—which insisted that updating these standards is a frequent occurrence that happens every few years—to hold a public hearing on Jan. 28 for people concerned about the new changes.

As a college educator, Blain said she and other professors understand how powerful the classroom setting can be. It was a Black professor who taught a course on Black history that changed her life, she expressed.

“It was sitting in a classroom and listening to these narratives about courageous Black people whom I had not heard of before. Hearing those stories empowered me; hearing those stories made it clear that I could in fact contribute to society in a meaningful way,” Blain said.

Blain said it is important for students of any race or socioeconomic background to hear these stories and get a glimpse of how Black people have contributed in shaping American society.

Nurturing Local Leaders

Dr. Keisha Blain said what she finds most inspiring about Fannie Lou Hamer was her commitment to the idea of grassroots leadership and how she believed so passionately in nurturing local leaders.

“She often criticized others who might come into a community and show up thinking they have all the answers,” Blain said. “You may come into a community, and you may have ideas about what needs to happen in the community, but what needs to actually happen for any sort of effective political or social movement is to tap into the local talent, to tap into those who are on the ground.”

The “Until I Am Free” author said she sees this in the Black Lives Matter movement where local chapters in different communities have brought together various activists on the grassroots level to work together and figure out how to move forward in their community, she said.

“That spirit of allowing people within their communities to emerge as leaders and not simply pushing this narrative (of) one or two individuals who we’ve anointed as the spokesperson or spokespeople for the race, to shift from that model. And I think that is one example of Hamer’s spirit extending to this current day,” the historian added.

Aunjanue Ellis said it is truly hurtful to see posters and t-shirts that say “I am not my ancestors” because some young people are disregarding individuals like Fannie Lou Hamer.

“Mrs. Hamer was one of the most radical and militant figures in the freedom rights movement. I mean she in my mind is an insurrectionist. I see her in the lineage of Nat Turner. But if you don’t know her, then you say something like I am not my ancestors,” Ellis said.

Ellis is excited for this documentary to provide a new opportunity for students to learn about Hamer, Ella Baker and other women that were the vanguard of this civil-rights work. She hopes people watching will tell the young people in their lives about this documentary.

Monica Land said her aunt Fannie Lou was relatable, resilient and that determination is what is so inspiring. People respond better to people, especially those in leadership positions, who look like them, sound like them or come from where they come from and that’s why her aunt was so effective, Land said.

“You see the young people with a sign that says ‘Nobody’s free until everybody’s free’ or ‘I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.’ You really have to wonder if they really know who aunt Fannie Lou is or did they just hear the quote and relate to it?” the great niece asked.

Land said when they first started the film project in 2007, Fannie Lou Hamer had three living daughters, although not biological. Fannie Lou Hamer was unable to have children of her own after she was given a hysterectomy without her consent—forced sterilization Hamer called a “Mississippi appendectomy”—while undergoing surgery to remove a tumor. She and her husband adopted children.

“The oldest one at the time, Vergie Ree, was very vocal. She was the one that people went to when they wanted information. Well, she passed away shortly after Aunt Fannie Lou’s 100th birthday in October 2017. She had another daughter named Lenora, that everyone knew as Nook, she passed away a couple of years ago. Well Jackie, that everyone knows as Cookie, she’s the only one left,” the niece explained.

Land said Jackie has a voice like no one else, and her personal relationship with her mother can not be imitated. She is hopeful that working with Jackie on this project will help get her voice out because there are so many projects, movies and plays in the work that do bit confer with Jackie.

“To me, that is a shame because she can provide an insight nobody else can. I’m very happy with this project, and I’m happy to be introducing her to different media outlets to allow them to hear her voice, tell her truth, tell her story because she actually is the torch bearer. I’m just an assistant.”

To watch the replay of the “Finding Your Voice” panel, visit World Channel’s youtube here. To learn more about Fannie Lou Hamer and the Sunflower County Film Academy, visit here. To watch “Fannie Lou Hamer’s America”, watch it on PBS here or on World Channel here.