It was Francisca Morales Diaz’ last week at the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center in mid-March when guards told her and the 71 other women in her cell block that they would soon run out of toilet paper and soap, even as the novel coronavirus was spreading across the south. Diaz, a diabetic whose disease makes her especially susceptible to COVID-19, had already spent nearly eight months in ICE custody in the prison and apart from her family back in Laurel, Miss.

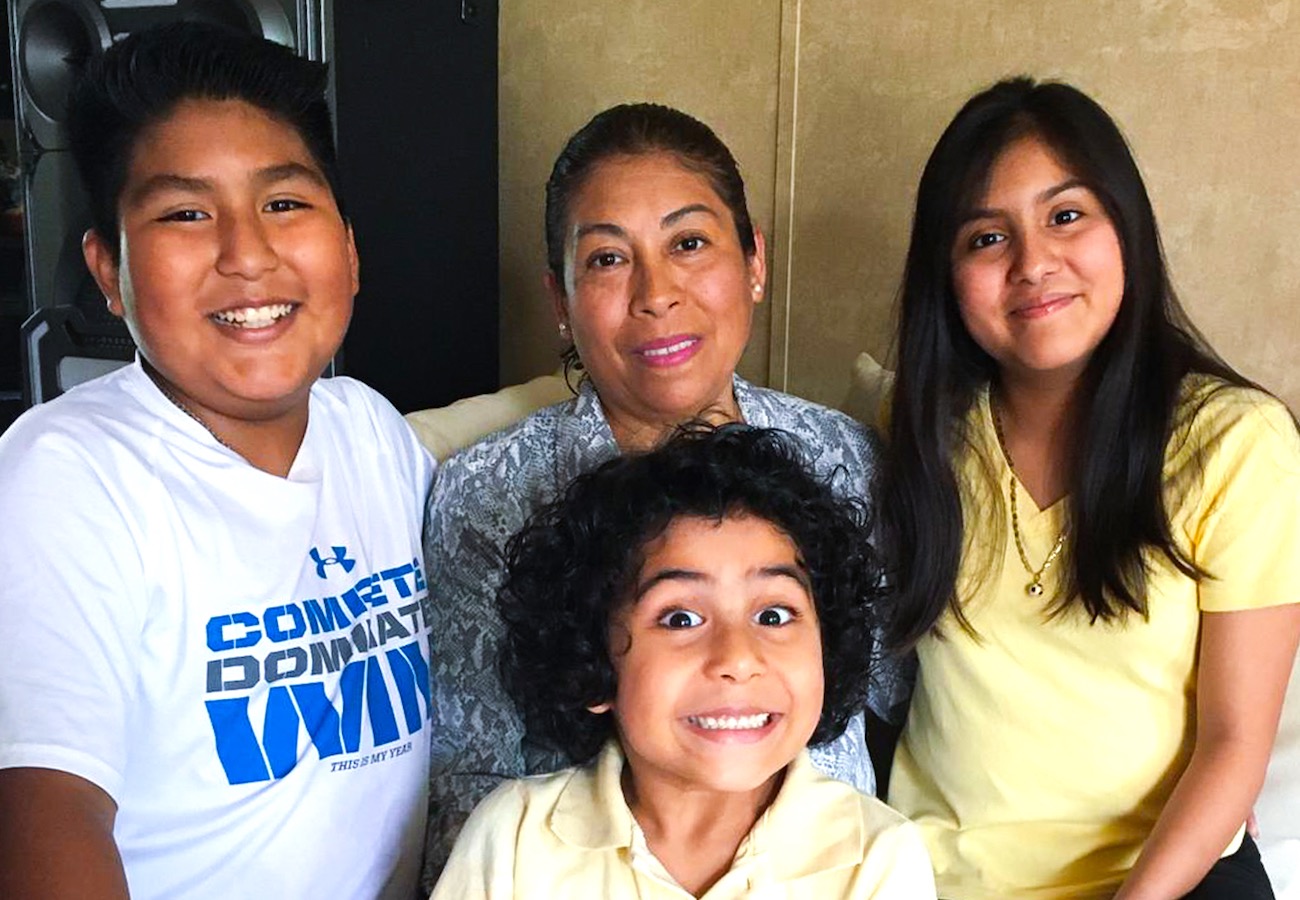

Diaz was among the 680 Mississippi poultry-plant workers whom ICE agents arrested during a series of one-day immigration raids in early August 2019, leaving dozens of children stuck at school with no parents to pick them up. The agency still has not charged any of their employers, but many of the immigrants who were arrested remain in ICE facilities in Louisiana, where the pandemic has exploded in recent weeks.

By mid-March, the women in Diaz’s cell block were growing concerned that the virus may have already made its way into the facility.

“It’s very alarming. … The detainees certainly believe there are COVID-19 cases in that jail,” Rachel Taber, an organizer for the Southeast Immigrants Rights Alliance Network in New Orleans, told the Mississippi Free Press Saturday.

‘Many Will Die If We Are Not Released’

On March 20, Taber drove to Basile in Louisiana’s Acadia Parish to pick up Diaz, who had finally bonded out, and return her to her family in Laurel for the first time since the raids swept her and other immigrant workers up last August. Three days after she left the Louisiana facility, Diaz shared her experiences with Taber, who provided the Mississippi Free Press with a translation of those remarks.

Diaz warned that the people at the prison are in serious danger of a potentially lethal COVID-19 outbreak because of the conditions there. There are only three nurses in the facility, which holds more than 500 people, she told Taber. An English-speaking doctor visits just once a month and guards who are not fully bilingual or trained in medicine act as interpreters between medical professionals and detainees, Diaz claimed.

“Women would get sick with severe coughs, fever, and they wouldn’t give them medical attention,” Diaz told Taber in Spanish on March 23. “You might be in serious pain the whole day, and all they would do is give you a pill. … If the guard doesn’t ‘feel’ you’re sick, that’s it. You won’t make it to the nurse.”

One woman, she said, had “a horrible fever,” sweats, chills, and trembling in early March.

“They didn’t want her to go to the nurse. They just brought a pill to her,” Diaz said. “You pretty much beg just to get an ibuprofen.”

The GEO Group owns the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center, formerly the South Louisiana Correctional Facility. The private-prison company contracts with ICE around the country and has been one of the top corporate beneficiaries of Trump’s immigration crackdowns. On its website, The GEO Group says that it is taking steps to prevent the spread of COVID-19, that none of its facilities “are overcrowded,” no facilities “lack access to regular handwashing with clean water and soap,” and that “all of our facilities provide 24/7 access to health care.”

Inmates there have long complained of ill treatment. In the summer of 2009, around 100 inmates in the Acadia Parish prison staged five back-to-back hunger strikes to protest overall poor conditions and substandard medical care.

On March 31, M*, a doctor from Cuba who is now detained at the South Louisiana facility, told Taber that she expects dire consequences for herself and her fellow detainees unless something changes quickly.

“There’s no way to ‘distance’ here,” she said. “We sleep in bunk beds on top of each other, in columns with less than a (few feet) between us, head to toe. We use the same cafeteria as those in quarantine with no cleaning in between. … My medical opinion is that many people will die if we are not released.”

Even before ICE confirmed any COVID-19 cases at its facilities, the agency began 2020 counting inmate deaths from other causes, including illnesses, at least one botched surgery and suicides. By March 23, 10 undocumented immigrants had died in ICE custody this year so far after Ramiro Hernandez Ibarra, a 42-year-old Mexican man, died of septic shock. The detention centers are also notorious for disease outbreaks; last year, a mumps outbreak swept through dozens of ICE facilities across the country.

M, the Cuban doctor, told Taber that it will prove even more difficult to contain COVID-19 outbreaks once they begin spreading through the detention centers. Immigration courts have closed or slowed their processing of detainees’ cases, and South American countries where many ICE inmates are from, such as Guatemala and El Salvador, began closing their borders to deportation flights or limiting them last month, so even as ICE continues to arrest and detain more immigrants, fewer are leaving the already crowded facilities.

“This will be a massacre,” M told Taber.

Avoiding ‘Wildfire Contagion’

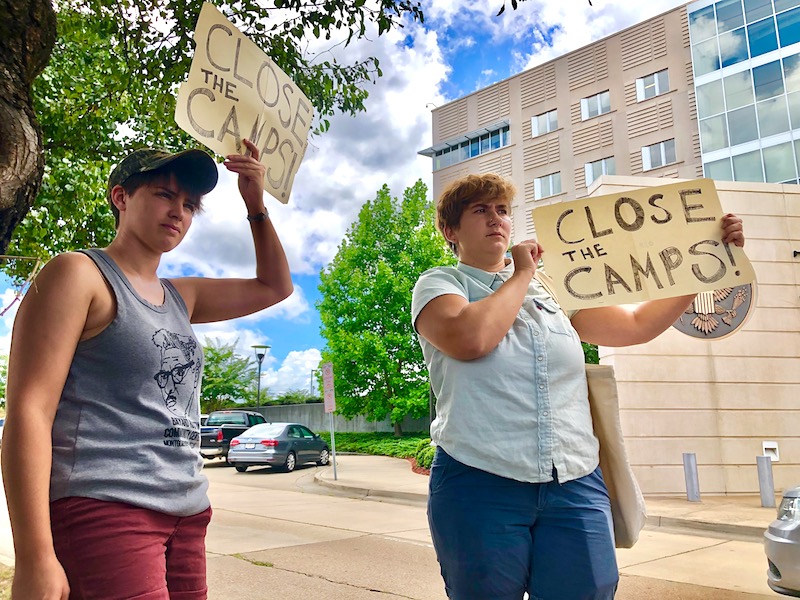

In an April 3 letter to Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell and U.S. House Rep. Cedric Richmond, a Democrat whose district includes most of New Orleans and the regional ICE field office, a group of 28 activists, clergy and other leaders from across the southeast said the detainees should be released before the virus sweeps through the detention centers.

“Freeing people from detention is the only way to prevent COVID-19’s wildfire contagion through rural Louisiana’s large population,” the letter reads. “Doctors nationwide have called for decarceration to stop the spread. … Many Louisiana jails and prisons house larger numbers of people than the rural communities that surround them, in towns ill-equipped to address how an outbreak might affect prison staff, their families, and local hospitals where detainees in critical condition will be transferred for care.”

Last week, U.S. Congressman Bennie Thompson of Mississippi’s 2nd Congressional District cited similar conditions at other prisons in Louisiana and across the country as he urged the government to begin releasing immigrant detainees, and allowing them to live at home as their cases work through the system. Otherwise, the Mississippi Democrat warned, the crowded facilities “will inevitably become breeding grounds” for COVID-19.

“We are calling on ICE to increase the use of alternatives to detention for immigrants in their care during this growing pandemic,” said Thompson, the chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security, which oversees the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. This is not only for the health of these immigrants, but also for the health of the DHS frontline workers and the general public, he said.

At one prison in Louisiana, the Federal Detention Center in Oakdale, dozens of inmates and personnel have tested positive for the virus, with some hospitalized, and five inmates have died. Dozens more are in isolation with suspect symptoms. With the outbreak so widespread at Oakdale, officials stopped even bothering to test inmates last week. Though the Oakdale facility is not an ICE detention center for immigrants, Thompson and immigrants’ rights advocates worry that it is a preview of things to come for thousands of immigrants.

“It is clear that ICE detention facilities, including local and privately contracted facilities, are unable to properly follow CDC standards set to combat the spread of the coronavirus,” Thompson said in his April 2 statement. “Without action, these facilities will inevitably become breeding grounds for the virus.”

A decade ago, 90% of detained immigrants were granted parole requests and allowed to live in their homes while awaiting trial. That changed in 2018, though, when the Trump administration began rounding up immigrants en masse, including thousands of children who have been separated from their families, and denying parole requests. By 2019, the U.S. was granting only about 1% of parole requests for detained immigrants.

On April 1, the Center for Constitutional Rights and the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, asking for the release of 17 medically vulnerable inmates in detention centers in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. Refusing to allow them to return to their homes, the organizations warned, “renders the continued detention of these individuals a potential death sentence for a civil immigration violation.”

‘I Am Scared That I Will Die in This Detention Center’

Diego Carrillo Och, a 65-year-old Guatemalan immigrant whom ICE arrested during last year’s poultry-plant raids in Mississippi, said in a court filing that he would go back to live with his cousin in Forest, Miss., if released. He told the court that he fears the guards may not be taking enough precautions at home and may bring the virus into the Richwood Correctional Center where ICE is holding him in Richwood, La.

“I am scared that I will die in this detention center from coronavirus,” Och said in the court filing. “Medical care here is terrible. When one of us has a headache or fever, the medical staff doesn’t provide us with medicine. They just ignore (us). That’s my concern—that if I fall ill they won’t do anything.”

Och says he sleeps in a triple bunk bed in a large room with 66 other detainees. The beds are about half a meter apart, he said, and the men all share four toilets, four phones, and seven showers. Before ICE moved him to Richwood, they held him at the Adams County Correctional Facility near Natchez, Miss., a facility owned by CoreCivic, a private-prison corporation that ICE began contracting with there last year.

Edilia Del Carmen Martinez, a 53-year-old woman from El Salvador with diabetes who is currently at the Adams County facility, described the medical care at the facility as “inadequate” in a separate filing, and said the doctor’s office was “unsanitary.” Guards and staff do not wear protective equipment, she said, adding that she shares a room with 120 other women.

“There are flyers up here that say that we should wash our hands for 20 seconds with soap, but I have no soap. There is only 1 soap dispenser and it’s broken. I can only wash my hands and body with water,” Martinez said.

On its website, CoreCivic says that all employees are being screened upon entering the facilities and that its facilities are following CDC recommendations for cleaning and the use of personal protective equipment.

On Monday, the Center for Constitutional Rights announced on Twitter that the court had dismissed the petition it had filed on behalf of the 17 inmates, citing a “lack of jurisdiction.”

“It is galling that a court would privilege some technical legal conceptions over the lives of 17 medically-vulnerable people, but we and our partners will continue to fight in court for them and others who are detained,” CCR tweeted. “Our clients are desperate to shelter at home, with their loved ones, not in the ticking COVID-bombs that are unsanitary, crowded, and highly infectious ICE detention facilities.”

Detainees and immigrants’ rights groups are not the only ones calling for ICE detainees to be released, though. Former ICE Acting Director John Sandweg is arguing for their release, too.

“When you look at the population of ICE and who’s in these detention facilities, and you recognize that only a small percentage pose any public safety threat, when you recognize that their immigration proceedings can continue even if they’re out of custody, and when you look at the thousands of ICE officers, contract guards, and employees who have to go to those facilities every day, who frankly are just as much at risk of catching COVID-19 because of their exposure to the facilities themselves, it seems just very commonsensical to me to say, let’s go ahead and downsize the population of the detention centers dramatically,” Sandweg told Democracy Now in late March.

‘Our Safety is Not a Priority’

For most of the past decade, only two ICE detention centers operated in Louisiana. Last year, though, the U.S. government opened 10 more in the Bayou State. On March 23, the Federal Bureau of Prisons transferred custody of one of its inmates, a 52-year-old man from Mexico, to ICE, and moved him to the Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center in Evangeline Parish, another GEO Group-owned prison where the government is holding around 1,000 immigrants, including some of the poultry-plant workers immigration agents swept up in the Mississippi chicken plant raids last summer.

On April 3, ICE announced that the transferee had tested positive for COVID-19. Though he had been in ICE custody since his transfer from the Federal Bureau of Prisons on March 23, the man had not been in contact with any of the roughly 1,000 detainees at Pine Prairie because ICE placed him in quarantine as soon as he arrived in consideration of the Oakdale outbreak, the agency said in a statement earlier this month.

A Cuban doctor who was detained in Pine Prairie described it in court filings last year as “unsafe, unsanitary, and discriminatory conditions.” Ventilation was poor, detainees got incorrect diagnosis for illnesses, and water dripped onto the doctor’s bed while mold grew on the wall above his pillow, he claimed.

“It has become quite clear to me that our safety is not a priority of the staff here, which is deeply upsetting,” the doctor said in court documents last June, though ICE disputed the allegations.

Pine Prairie was one of the ICE facilities hit by mumps and chickenpox outbreaks last year, and hundreds of detainees were quarantined in response.

In addition to the confirmed COVID-19 case at Pine Prairie, ICE has confirmed that two personnel members in Louisiana have tested positive for COVID-19.

This afternoon, LaSalle Parish Sheriff Scott Franklin announced in a Facebook post that a second Louisiana ICE detainee has tested positive for COVID-19 at the LaSalle Correctional Center.

“He along with the other detainees in his dorm have been shipped to another facility that has a dorm set up for quarantine,” Franklin wrote on Monday, April 6. “We should all be acting like everyone has the virus and follow all CDC protocols.”

On Friday, U.S. Attorney General William Barr directed the Federal Bureau of Prisons to prioritize early release for some “vulnerable” prisoners at the Oakdale prison and several others that have seen COVID-19 outbreaks across the country, including in Ohio and Connecticut. While older people and those with certain health conditions are at higher risk of dying if they contract the novel coronavirus, a significant number of those who have died were young and healthy.

Neither Barr nor anyone else in the administration has taken significant steps to grant release to “vulnerable” people in ICE facilities, though. In an April 1 White House press conference, Barr said he was still focusing on other “threats,” like going after Mexican drug cartels.

“Obviously, during this crisis, we’re all focused above all else on COVID-19. But at the same time, our law enforcement and national security work must go forward, protecting the American people from the full array of threats,” Barr said.

A ‘Ticking Time-Bomb’

In the days before Francisca Morales Diaz left the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center last month, she told Taber, the six-dozen women in her cell block had to share just five bars of soap—all of which were gone within a day. Like M, Diaz told Taber she worried that inmates would not be able to practice social-distancing procedures that are necessary to prevent the coronavirus’ spread.

Taber told the Mississippi Free Press that ICE had Diaz and her cellmates in quarantine when she arrived to pick her up in Basile on March 20, and that the facility refused Diaz’s requests for her own medical records that day. The facility also would not confirm whether or not they had any novel coronavirus cases there, Taber said. The New Orleans-based organizer shared a recording that she says is from a discussion she had with a guard that day.

“We’re just trying to take care of her health. And this is very concerning,” Taber tells a man in the recording, referring to Diaz. “You’ve had her in quarantine. You can’t tell me anything about her condition. I don’t know if she’s sick or needs to get serious medical attention, and you’re refusing to answer any question about her medical state.”

Because the facility would not release Diaz’s medical records, Taber told the Mississippi Free Press, she was unsure what kind of precautions she needed to take before Diaz got in the car with her. In the recording, she asks the man if anyone in the facility had COVID-19.

“I cannot confirm or deny any of those questions,” the man, whom she identified as a guard, tells her.

“Why not?” Taber asks.

“Because I’m not at liberty to divulge any of that information.”

“Who has instructed you—?,” Taber begins, before the guard cuts her off.

“Give me just a moment,” he says.

Shortly afterward, Taber continues asking the man why the facility will not release Diaz’s own medical records to her.

“The federal law says you do have to release somebody’s records under HIPAA. You have to release their own medical records to them,” Taber says. “And we’re here concerned because she’s been in quarantine. You’ve not been able to confirm for me if there has been COVID-19 here or not. And you’re refusing to provide medical records to us. Can you confirm if there’s been a case of COVID-19 here?”

“I’m not answering any questions as long as you have me on a recording,” the man says.

Taber told the Mississippi Free Press that the guard never answered her questions, and neither the facility, nor the State of Louisiana, nor the U.S. government has confirmed any cases at the Basile facility. But Taber said detainees have told her they believe there are COVID-19 cases among them already.

Some detainees mentioned a detained Ecuadoran cafeteria worker who was removed from the facility about three weeks ago after exhibiting COVID-19-like symptoms, Taber said. Detainees made the same claims in interviews with The Intercept last week, with the outlet quoting several Cuban detainees at the facility, including Rosa Pino Hidalgo, who also described an ailing Ecuadorian woman who worked in the cafeteria.

“She served food and cleaned up after meals,” Pino Hidalgo told The Intercept in Spanish, saying the woman was sick with a sore throat, high fever and diarrhea—all known symptoms of COVID-19.

“She spent three days in bed. There has been a lot of flu going around here, and the medical staff gave her a flu test. It came out negative. Then a doctor and nurse went into her dorm, dressed in medical gowns, masks, gloves and protective eyeglasses. We’ve never seen that when people have the flu. They carried the woman out on a gurney. Her body was also in protective gear and she was hooked up to oxygen.”

The women’s cell block was put on quarantine afterward, the detainees told The Intercept, and guards began passing food under the door and wearing medical gowns for protection. The facility told detainees that the quarantine was related to a flu outbreak, but the detainees told The Intercept that they doubted those claims. The Ecuadorian woman returned to the facility in late March and was being housed in its medical unit, they claimed.

“I’ve been there, and she’s in a room with a sign on the window that says, ‘confirmed or suspected COVID-19,’” The Intercept reported Yadira Labrada Merino, another Cuban detainee, saying.

While detainees and their advocates alike doubt ICE’s claims, they and a number of allied experts and lawyers are certain that COVID-19 is a “ticking time-bomb,” as the Center for Constitutional Rights described it.

In her March 23 testimony, Diaz, through Taber, asked for help to get the immigrants she was locked up with and others like them out of the detention centers before the virus exacts a deadly toll.

“We’ve got to get folks out of these jails. They’re suffering too much here. They would just let you die in that jail,” Diaz said. “They’re not very concerned about detainees. They see us as disposable.”

Neither ICE, GEO Group or CoreCivic responded to a request for comment by press time Monday.

*M requested not to be identified, fearing for her safety.

The Mississippi Free Press has an interactive map showing diagnosed coronavirus cases across the state and one showing the number of ICU beds in counties across the state.