I just got an email from a Black woman and Mississippi ex-pat who grew up in Noxubee County. She was touched deeply by the “(In)Equity and Resilience: Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” pieces we’ve published in recent days about her home county.

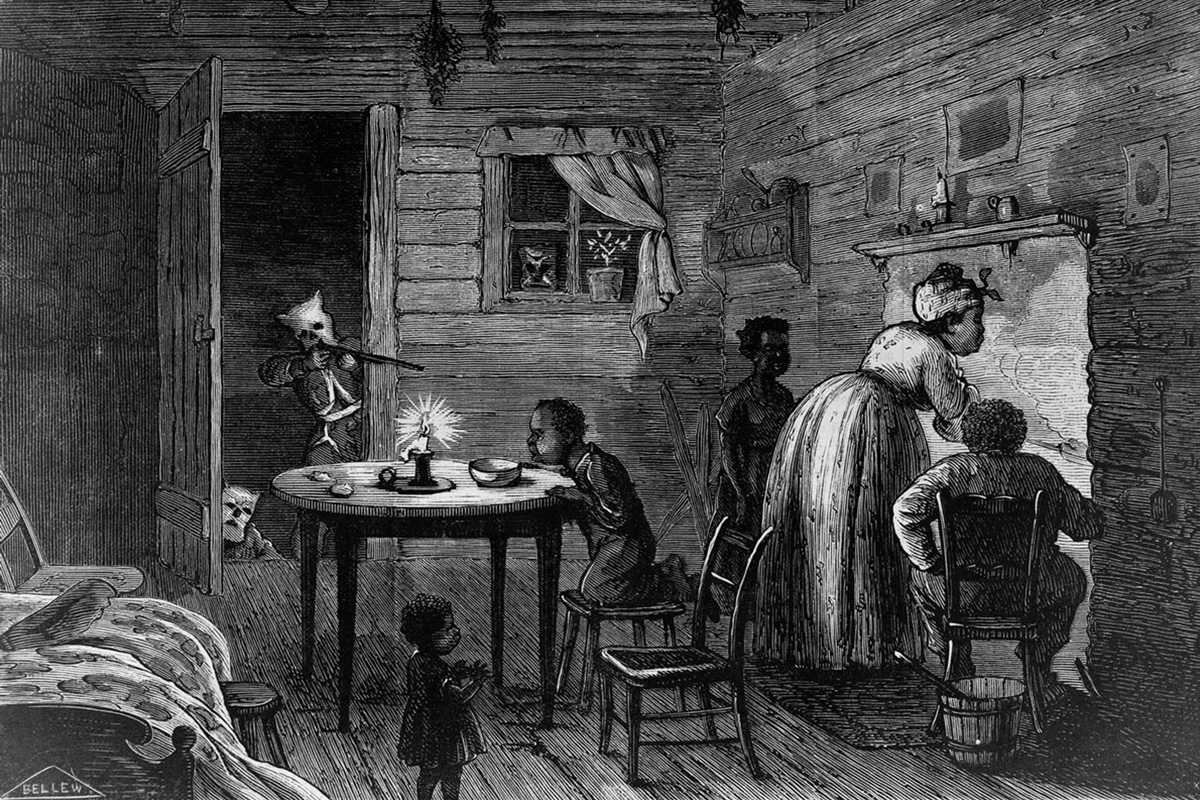

After she learned through our reporting that white terrorists systematically burned Black schools and terrorized and even killed Black educators there, she thought of her own great-grandmother who had been a teacher there early in her life, but then stopped.

Now, this reader wants to know if her great-grandma was bullied out of teaching Black children, and intends to find out.

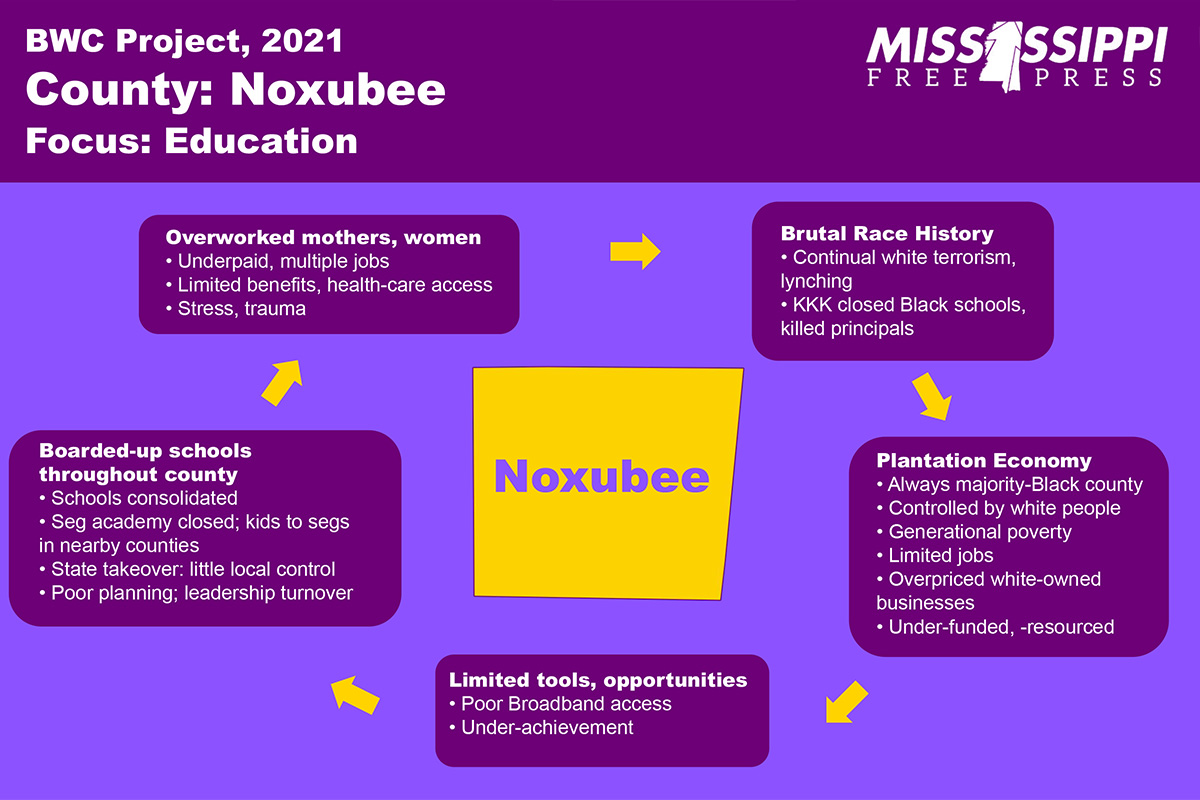

In this Jackson Advocate-Mississippi Free Press collaboration, the BWC Project team, as we call it for short, has spent a year planning, reporting, hosting solution circles of Black women and doing deep historic research on, so far, three counties. Our big, hairy goal is to show why COVID-19 initially affected Black women in our state harder than any other group including even Black men. We posited that this was due to systemic and historic inequities, but our job is to prove it—and not just to the people most affected who already know what embedded barriers they must overcome.

They are our teachers.

In our initial focus counties—Hinds and Holmes are coming soon—the team is following where Black women on the ground take us. Writer Torsheta Jackson is a Noxubee native with years of teaching experience, so that led her to an education focus after talking with educators she knows on the ground about the challenges that existed making it harder for Noxubee’s families when COVID-19 hit. But she followed where Noxubee’s Black women led her, resulting in a list of disparities that need solutions, including internet access, mental-health resources, access to quality health care, education and teacher resources and more.

Ultimately, our goal is solutions journalism (with project startup support from the Solutions Journalism Network)—for instance, Torsheta’s upcoming piece is about ways to make broadband more accessible and equitable in Noxubee County and beyond. But here’s the rub in what we are calling systemic reporting and how it’s different. It isn’t all that hard for a journalist to figure out that Black families in Noxubee County have internet problems; people and leaders who can change it already know it. But somehow solving the problem is never the priority in a community that has long been ignored and neglected.

What is harder about this journalism path is that we are digging backward and connecting puzzle pieces for our readers that show how systemic inequities were established long ago and then passed forward, creating today’s disparities and barriers, with too many people blaming those who suffer the most from society’s neglect.

Look, this team is made up of native Mississippians; we’ve watched the chairs on the Titanic of inequities in our state moved slightly if at all for decades, even when the problems are apparent. And we’re sick and tired of being sick and tired of everything devolving into partisan games and finger-pointing over core issues like education; disparities ultimately destroy communities, towns and make quality of time worse for all of us. It is time for truth and collaborative action.

That means that while doing a good solutions piece about broadband access in Noxubee County is admirable, it may well not lead to real change for those families. And that’s especially true if it ignores all the deep systemic reasons that Black Noxubee Countians face so many created barriers. Put simply, the usual journalism is not moving enough needles. Effective solutions must use the full, uncensored picture from the ongoing effects of systemic race violence to the harmful realities of many historic segregation academies, even as that is difficult for many people who don’t want to “dredge up the past.”

What gets me as a white Mississippian about the lie that historic truth teaches that all white people are evil, or whatever, is that uncensored history actually reveals white heroes who were also threatened, whipped or killed for trying to do the right thing. In my historic research on Noxubee County in this project, I now know the names of white people who changed to do the right thing—former Confederate soldiers, planters and even sons of slave owners/traders like John Taliaferro who put their lives on the line after the Civil War to fight Klan violence and for Black schools and access to the voting polls. We need to be able to celebrate their courage, too.

What you’ll find in this series, by design, is not just the reasons for the barriers, but remarkable Black resilience amid horrific conditions: like matron and formerly enslaved Lydia Anderson who refused to have sex with her employer and then testified to Congress in 1871 about his sons who beat her wearing masks, horns and “dresses,” as she put it. Or Macon native Dr. Dan Sherrod who barely escaped being lynched there in 1906 because he blocked white people’s view at a Macon concert, then got bashed over the head with a nightstick. He moved to Meridian after a white mob burned his home and library and became a remarkable success and leader.

We need to know all their names.

Mississippians deserve the truth about how today’s conditions got here. Kimberly and I started the Mississippi Free Press to tell this shaming-the-devil truth, as she calls it—the real and difficult causes, not just the obvious symptoms—so that we can then report possible solutions county to county. We intend for our reporting to inspire people to stand up across divides and decide that Mississippi can finally be the equitable and inclusive home all of our people deserve—from the descendents of Lydia Anderson and John Taliaferro to those of Mississippians who committed the atrocities, who need the truth to choose to be different from their ancestors, a decision I made years ago and have never looks back. We are not our ancestors; we have a chance to be better and to help our state heal from their transgressions.

The success of the state we love is about what we do today together, based on real knowledge about why systemic barriers exist that lead us to how to repair them and give everyone a fair chance at opportunity and success.

This is hard, time-consuming and stressful journalism, all. I can’t explain the dreams I had while reading the testimonies of Black and white people the Klan tried to maim or kill, but I’m so grateful to now know these heroes’ names. We and our whole team believe nothing less will take our state and our people where we all deserve to be together. We thank all of you for sharing, evangelizing, donating and showing us love on this journey.

Mississippi needs each of you to help us build a model of systemic, truth-telling journalism for the nation.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.

This Voices essay introduces the “(In)Equity and Resilience: Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” collaboration between the Mississippi Free Press and the Jackson Advocate. Visit the BWC Project website and email azia@mississippifreepress.org to get involved with solutions circles or offer suggestions and input. Email me at dtjohnson@thejacksonadvocate.com or MFP Publisher Kimberly Griffin at kimberly@mississippifreepress.org if you’d like to become a sponsor of this collaboration as it continues.

Also see Torsheta Jackson’s overview of systemic disparities in her home county of Noxubee County, the first in-depth county overview in the BWC Project, focusing on education. Visit the full BWC Project microsite here.