The U.S. Department of Justice is seeking an end to its decade-long struggle with the Mississippi Department of Mental Health over inadequate community care, issuing its final plan for the ailing system last Friday.

The DoJ’s plan demands a quantifiable investment in community health services, asserting that gaps in Mississippi’s mental health system deny individuals the right to maintain an independent life in their communities. “The State’s unnecessary reliance on State Hospitals affects hundreds of adults with serious mental illness in Mississippi each year,” the remedial plan reads.

That reliance, it adds, violates the Americans with Disabilities Act, which the landmark 1999 Olmstead decision determined prevents the unjustified segregation of disabled individuals away from their familial and communal lives. “Many admissions to the State Hospitals last months or years,” the document continues. “At the Mississippi State Hospital continuing care unit, for example, the average length of stay was around 4.5 years.

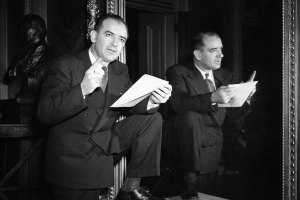

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, presenting the opinion for the majority in Olmstead, explained the unlawful nature of excessive detainment in state mental health facilities. “Unjustified institutionalization of persons with mental disabilities we hold qualified as discrimination by reason of a disability within the compass of the ADA’s Title II,” Ginsburg said.

Necessary Services Ruled ‘Illusory’

Joy Hogge, executive director of Families as Allies, spoke with the Mississippi Free Press on May 24, addressing the demands contained in the federal government’s remedial plan and how the State of Mississippi intends to respond.

Hogge explained that measurable steps toward protecting the rights of individuals with mental illnesses to remain in their communities and homes were the inevitable outcome of Olmstead, which Mississippi had never adequately pursued. “We didn’t engage in that organized process of establishing an Olmstead plan,” Hogge said. “The Department of Justice did an investigation of the state in 2011 and said ‘you appear to be in violation of the ADA.’”

The Court found chronic lack of a proper Olmstead compliance manifested in a lack of services and coordination with Medicaid, resulting in gaps in coverage for preventative care that could be the difference between a brief encounter with a qualified mental health-care professional and a removal to confinement in a state mental institution.

The frontline service missing is the “Mobile Crisis Team,” an alternative to calling 911 in moments of crisis, capable of providing emergency mental health services and evaluations.

“The Department of Justice plan (is intended) to have the State look at what kind of infrastructure needs to underlie a good, consistent crisis response team. What does the State need to come up with to support local community mental health centers or regional community mental health centers in setting that up?” Hogge said.

The plan acknowledges that mobile crisis teams became theoretically available back in 2012. However, the institution of mobile crisis services on paper does not necessarily translate to the service’s availability for all Mississippians.

“The Court found (that) Mobile Crisis services remain ‘illusory’ in many parts of Mississippi. … Mobile Crisis Teams shall be available for phone and in-person responses to individuals experiencing mental health crisis 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year throughout each CMHC region,” the plan states.

An additional component to the crisis response needs of the State’s mental health-care system is the Crisis Stabilization Unit, a short-term supervised care center for adults in severe psychiatric distress. These stabilization units can provide a stopgap for an escalating mental health event that could otherwise lead to full institutionalization.

Hogge cautioned that services like the crisis stabilization unit are only as good as the constellation of support infrastructure and qualified professionals around them. “A crisis stabilization unit in the community is great,” Hogge said. “But unless those mental health centers have the training, support, infrastructure and backup behind them, they can end up doing the same thing as the state hospitals. You don’t want to just have crisis beds where you’re putting people.”

If the court again rules in favor of the federal government, Mississippi will have two years to address its gaps in mobile crisis services, and one year to provide adequate crisis stabilization units to all its mental health-care regions.

Higher Appeals Likely

Mississippi’s own Department of Mental Health argued less than a month ago that, however negligent it had been in the past at implementing a proper Olmstead plan, it has since addressed all necessary deficiencies.

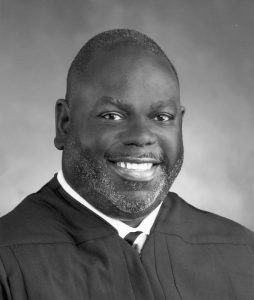

U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves, who previously ruled against the State in 2019, will weigh this argument against the DOJ’s more comprehensive plan in the coming weeks.

If Reeves again rules against the State of Mississippi, it would be mandated to follow the extensive DOJ plan, with concrete metrics for monitoring its success in expanding intervention services to prevent unnecessary institutionalized as well as re-entry programs to ease formally institutionalized Mississippians back into their communities.

On May 21, the Daily Journal reported Attorney General Lynn Fitch “would not rule out” appealing the decision to a higher court if necessary—an outcome that seems likely based on Reeves’ previous rulings.

Still, Fitch expressed her confidence that Judge Reeves would “take a hard look at” the state’s plan, which pledges to pursue the central demands of Olmstead without the significant federal oversight and measurement of the Department of Justice.

Hogge favors the strict statistical demands of the federal government’s plan, which includes careful monitoring of the Mississippi Department of Mental Health’s accomplishments in expanding services. Until then, it is the contention of the Department of Justice that Mississippi is sorely behind on its basic social services.

Hogge sees the State’s plan as light on details and weak on leadership. “I don’t think there’s been the vision, experience or expertise within the Department of Mental Health to even know how to craft such a plan,” she said. “And it’s a plan that should have been crafted 20 years ago and built on: and now they’re trying to take people who don’t have that area of expertise and build that plan. That’s why it comes across, at least to me, as hollow.”