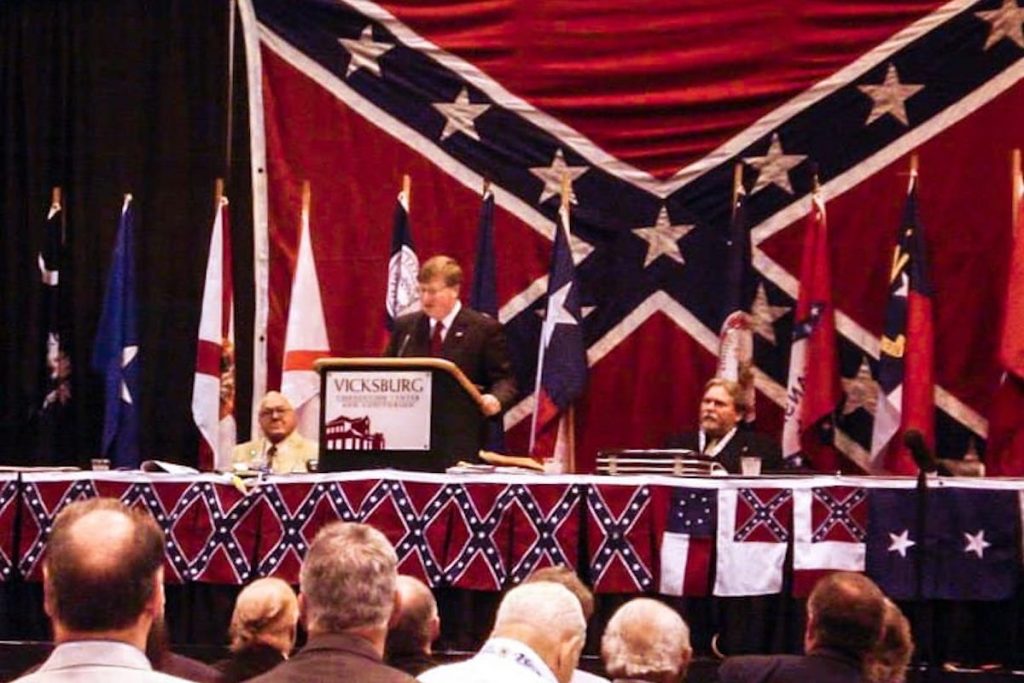

Mississippi’s governors, both Republican and Democratic, have for decades signed proclamations declaring April “Confederate Heritage Month.” This year is no different. While 2021 finally witnessed the adoption of a new state flag, cleansed of the Confederate battle flag that had been embedded there since 1894, Gov. Tate Reeves has not abandoned the Lost Cause and, right on cue, signed yet another proclamation dedicated to honoring the Confederate tradition.

Confederate monuments, of course, have been at the center of national debates since the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Throughout the South, protesters took aim at these statues because they symbolized the same issues that led to Floyd’s death—systemic racism, white supremacy, and, relatedly, police brutality.

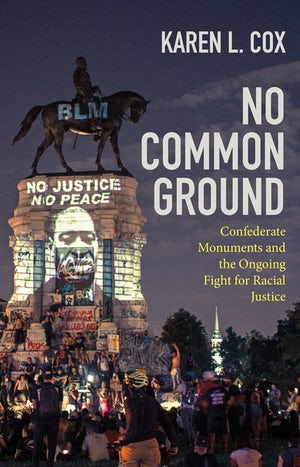

Yet the protest against Confederate monuments as symbols of racial injustice is not new. It is also not new to Mississippi. As I describe in my new book, “No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice,” that protest was front and center in 1966 during the now infamous Meredith March in Mississippi. Here is an excerpt from my book about James Meredith’s “March Against Fear.”

_______________

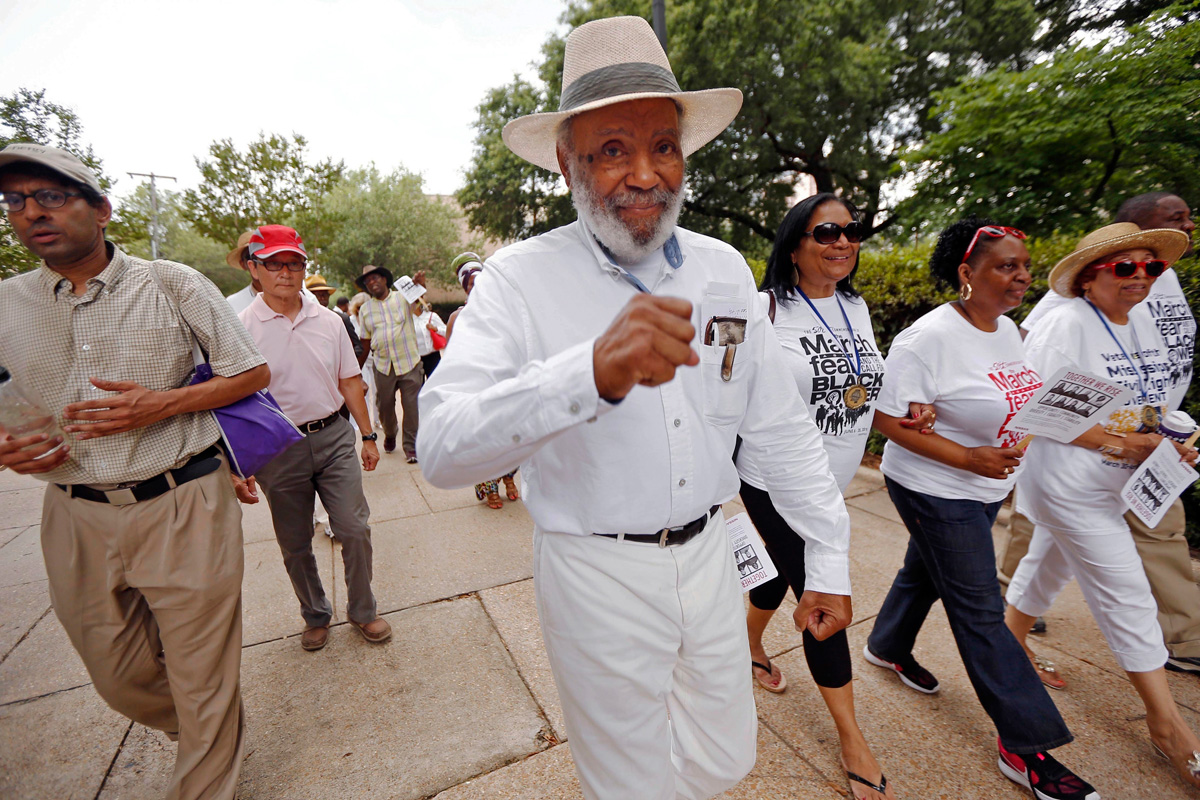

As the Civil Rights Movement won notable legislative victories, Black southerners were increasingly insistent in claiming the right not only to vote but also to occupy community space that, under the gaze of Confederate statues, had been barred to them. The push to register African American voters, especially in states like Mississippi where white resistance remained fierce, took on added importance, as did confrontations with monuments. This confluence of events was evident in 1966 when James Meredith—both a military veteran and a veteran in the battle against white supremacy, having integrated the University of Mississippi a few years before—decided on his own to lead a march from Memphis, Tennessee, through the heart of the Mississippi Delta, where large swaths of African Americans were still not registered to vote.

Some white Mississippians, still angry that he had integrated the state’s flagship university, were prepared to rid the state of Meredith even if it meant killing him. He did not hesitate. Mississippi was his home, too, and Black Mississippians were family. He sought to use the march not only to register voters but to help buoy people who were afraid to vote, which is why he called the journey between Memphis and Jackson a “March Against Fear.”

His trip, however, was cut short by a gunman, not far outside of Hernando, Miss., who emerged with a shotgun from the brush that lined the highway. He fired two shots, knocking Meredith to the ground, and then shot him a third time at close range before walking away. The police accompanying the marchers did nothing to stop him.

An ambulance whisked Meredith to a hospital in Memphis, where doctors pronounced him to be in satisfactory condition—but this did not stop the press from announcing that he had died, sending shock waves throughout the United States.

Once it was clear that Meredith did indeed survive, leaders from all the major civil rights organizations, north and south, saw an opportunity to galvanize people for the ongoing fight for equality. Both old guard and new guard civil rights leaders vowed to continue what he had begun. Eventually, Stokely Carmichael, Floyd McKissick, and Martin Luther King Jr.—the leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), respectively—assumed control over what was now being called the “Meredith March.”

In the days ahead, the march grew exponentially as it continued down Highway 51, which pierced the flat alluvial plain of the Delta. Confederate monuments had not been the object of civil rights protests in the 1960s, but as marchers entered each county seat, they often coalesced around those statues erected either on the courthouse lawn or in the center of town.

There, the central symbol of racial inequality that had dominated the local landscape for generations now stood facing the movement for racial equality African Americans, especially those Black southerners most affected by the racism of local whites, were now there to reclaim the public square for themselves, asserting the rights of American citizenship.

They instinctively knew and understood the history and meaning behind these statues. Granite and bronze memorials might technically be “silent,” but metaphorically they spoke volumes about white supremacy in these communities. When the Meredith March entered Grenada, Miss., in mid-June 1966, the significance of Confederate monuments as symbols of inequality became indisputable

_______________

On June 14, 1966, over 200 marchers, Black and white, spilled into the little town and made their way downtown along Grenada’s Main Street. They were joined by several hundred locals, and together they sang freedom songs. After combining forces, the column of marchers headed directly to the Confederate monument, which predictably sat in the town square. Grenada’s monument, erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1910, was of a lone Confederate soldier; the pedestal on which it stood displayed a bas-relief of Jefferson Davis on one side.

Since its dedication, local whites annually observed Confederate Memorial Day at the monument, extolling praise for the men who had fought to keep the system of slavery intact. Yet that day in 1966 was not about celebrating but confronting the Confederacy.

The crowd gathered around the monument and vocalized a new vision for their community, one free from white supremacy. A few of them even raised clenched fists in the air—the symbol of

Black Power. As horrified local whites looked on, Robert Green, representing the Southern Christian Leadership Council, climbed onto the monument to plant an American flag above the image of Jefferson Davis and declared, “We’re tired of seeing rebel flags. Give me the flag of the United States, the flag of freedom.”

George Raymond, a Congress of Racial Equality field secretary, climbed onto the monument next and, pointing to the likeness of Jefferson Davis, referred to him as “the joker up there.” The crowd responded with cheers.

Later that evening, Martin Luther King Jr. joined the marchers, and he also took to the steps of the Confederate monument. King was there to negotiate concessions from local government, which included the hiring of five Black registrars to register new voters and desegregating the library and public schools. King’s spirits were lifted by what he saw in Grenada, which was one of the earliest recorded examples of a racial justice protest converging around a Confederate monument and a harbinger of those seen decades later. And over the next few days the town saw a dramatic increase in voter registration.

_______________

As the march continued deeper into the Delta, white residents in Greenwood, Miss., however, prepared not only for the onslaught of protesters but to protect the town’s Confederate monument from the kind of desecration they believed occurred in Grenada.

The march entered LeFlore County on June 17, 1966, led by King, Carmichael, and Hosea Williams. But as they walked onto the courthouse grounds, they were stopped by policemen and told to keep off the grass. Behind the uniformed men stood the Confederate monument, dedicated by the UDC in 1918. Local officials had taken the additional step of protecting the monument by forcing eight Black prisoners from Parchman, the state penitentiary, to surround the statue, a tactic that was also used in Belzoni, Miss.

Posting Black prisoners to protect a monument to the Lost Cause was an insult not only to the marchers but also to the local Black community. Hosea Williams, an aide to King, shouted to white officers, “The only reason I’m not going onto that statue today is because you will beat these poor boys when they are back in jail.” He knew that while these men were being used as pawns to defend the monument, the state penitentiary was notorious for its mistreatment of prisoners, the majority of whom were Black men.

The “freedom march,” as King referred to it, eventually made its way to Mississippi’s state capital. Along the way the number of marchers ebbed and flowed from as few as 30 to over 1,000, but when the march finally arrived in Jackson on June 26, a crowd of 12,000 gathered. James Meredith had rejoined the march earlier, but by now it had grown into something larger than even he had envisioned.

While King had asked marchers to resist using Stokely Carmichael’s slogan, “Black Power,” because he believed it ran counter to the cause of integration, the chant of “Black Power! Black Power!” rang through the air as the crowd grew in size. As participants sang and shouted, the New York Times reported that some of them “tore occasional Confederate flags from the hands of white bystanders and ripped the pennants to shreds.”

The marchers had walked through downpours and blazing heat to get there. They had endured harassment and violence from white Mississippians throughout their pilgrimage as local and state law enforcement looked on. One resident in Greenwood had gone so far as to place a poisonous water moccasin in a box near where marchers set up tents for the night. But protesters were undaunted, standing tall against Confederate monuments in one town after another, rejecting the Lost Cause narrative that they represented, and reclaiming the spaces where they stood in the name of racial equality. This was their time.

Excerpt Ends.

_______________

The Meredith March and its confrontations with Confederate monuments provide evidence that their history is far more complicated than Lost Cause advocates would have you believe. These statues have long been flashpoints in the history of Jim Crow, civil rights, and protests for racial justice. They have never been symbols of a benign heritage. Neither are they silent. Confederate monuments, especially those stationed in front of county courthouses, have always stood for the preservation of the racial status quo.

That, too, is part of the Confederate tradition being commemorated this month.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.