“We must never forget the dream—and fight for a new inheritance, one woven not of exclusion but instead of that universal human spirit that calls us each home.”

– Dr. Raphael Bostic, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

For many Black Americans in the Deep South, homeownership is still a dream deferred.

A region marked by a history of racial violence and targeted exclusionary policies like redlining continues to see widening racial homeownership disparities. The U.S. government agency, Home Owners Loan Corporation introduced redlining in 1935, when it drew literal red lines on maps to delineate the perceived riskiness of making mortgage loans, and in fact directed lenders to “refuse to make loans in these areas [or] only on a conservative basis.”

Redlining policies allowed banks and mortgage lenders to deny loans based strictly on the borrower’s race and where they lived. These efforts successfully supplied housing to white, middle-class families, while simultaneously preventing Black families from gaining equity in homeownership and building generational wealth. Redlining was made illegal in 1968 with the passage of the Fair Housing Act. The Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 was intended to address its harms, but redlining’s legacy persists.

$352 Million in Lost Wealth from Mississippi Communities of Color

Redlining still influences the racial makeup of neighborhoods today. In fact, Black homeowners are nearly five times more likely to own a home in a formerly red-lined neighborhood than in neighborhoods considered more valuable or green-lined neighborhoods. This also has a direct relationship to stifling ability to build wealth. For example, in Birmingham, Ala., Black residents make up the majority of former red-lined areas and have lower incomes and property values.

While lenders no longer make loans based on a map marked with red or green lines, Black Americans still face discrimination, and predatory mortgage loans disproportionately affect them. Leading up to the 2008 foreclosure crisis, Black families were provided loans on less favorable terms than white families nationwide, even with similar credit profiles.

Mississippi provides a case study of these effects. For loans originated between 2004 and 2008, 30% of these loans to Black households completed foreclosure by 2012 or were at imminent risk, compared with 12% for white households. These foreclosures resulted in $352 million in lost wealth from communities of color in Mississippi. Unfortunately, not only has Black homeownership failed to recover since the recession, it has continued to decline. Specifically, Black homeownership rates in 2019 are the lowest point in 14 years at 51%.

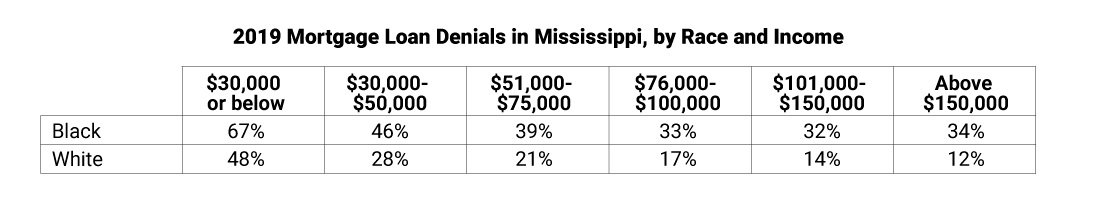

One contributing factor is disparities in denial rates. The denial rate for Black residents in Mississippi earning over $150,000 is higher than the denial rate of whites earning between $30,000 and $50,000. In other words, Black households earning three times as much income as other households still face higher denial rates when applying for a mortgage.

Figure 1: 2019 Mortgage Loan Denials in Mississippi, by Race and Income

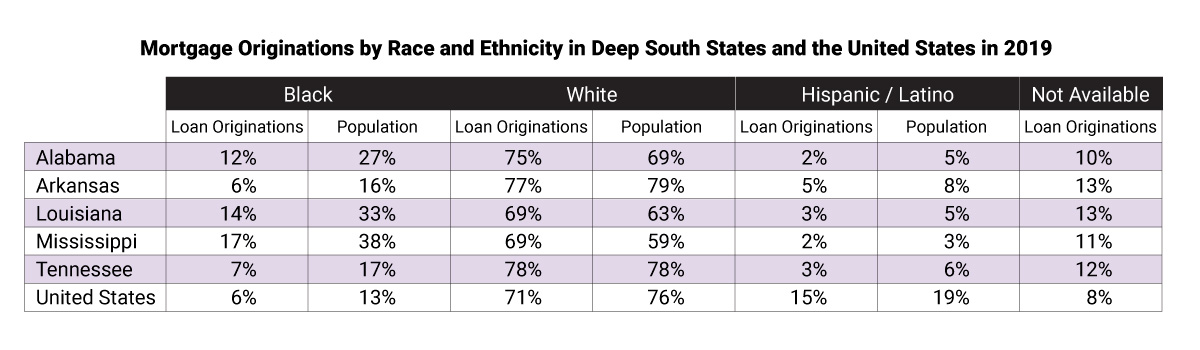

Ongoing disparities in access to mortgages is not unique to Mississippi. In 2019, the percent of loan originations for Black borrowers in Deep South states substantially trailed the percent of population they represent and the percent of loan originations for Black borrowers is less than half of their population as a whole.

Figure 2: Mortgage Originations by Race and Ethnicity in Deep South States and the United States in 2019

The Community Reinvestment Act: An Unfulfilled Promise

The Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 was intended to address the long-term effects of redlining and to ensure banks adequately serve the communities in which they do business. However, since its enactment, it has been implemented primarily on the basis of income rather than race.

Through the CRA, one of three regulatory agencies evaluate the banks, including the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation on how they are serving their whole communities. That includes those in low-income areas and communities of color, with lending and retail services, such as home-mortgage loans, small-business lending and community-development activities.

Over the last year, the regulatory agencies with rule-making authority for the CRA have been proposing changes with the stated goal to modernize the CRA. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency finalized its own weak rule in May, which the HOPE Policy Institute opposed, along with other partners serving Deep South communities. The FDIC also had a proposal under consideration, but has not issued an updated final rule at this time.

Historically, the federal banking regulators have issued joint CRA regulations. However, in September, the Federal Reserve released its own proposed changes to the CRA and asked some overarching questions on the CRA, such as: “In considering how the CRA’s history and purpose relate to the nation’s current challenges, what modifications and approaches would strengthen CRA regulatory implementation in addressing ongoing systemic inequity in credit access for minority individuals and communities?”

Race is inextricable from the CRA’s history, purpose, and the “ongoing systemic inequity in credit access for minority individuals and communities.” However, historically, the CRA has primarily used “low-income” as a proxy to identify communities and persons of color. Disparities in mortgage lending to people of color, as illustrated above, show the need for the CRA to include race in the metrics. Neither geography nor income are sufficient proxies for race, especially in places like the Deep South with a substantial portion of low-income areas.

Under the current rules, 98% of banks pass their CRA exams, despite the glaring racial inequities that persist in access to capital for communities of color, people of color, and businesses owned by people of color. Race should be included in the specific metrics by which banks are evaluated for CRA purposes.

Crumbling infrastructure, public-education inequities due to unequal property tax funding, and lack of access to nutritious food are just some of the racial disparities Black neighborhoods still face because of redlining. Policy makers can honor Black communities long past Black History Month by ensuring Black families are able to overcome the systemic barriers of redlining. Including race in the CRA metrics is a step in the right direction.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.