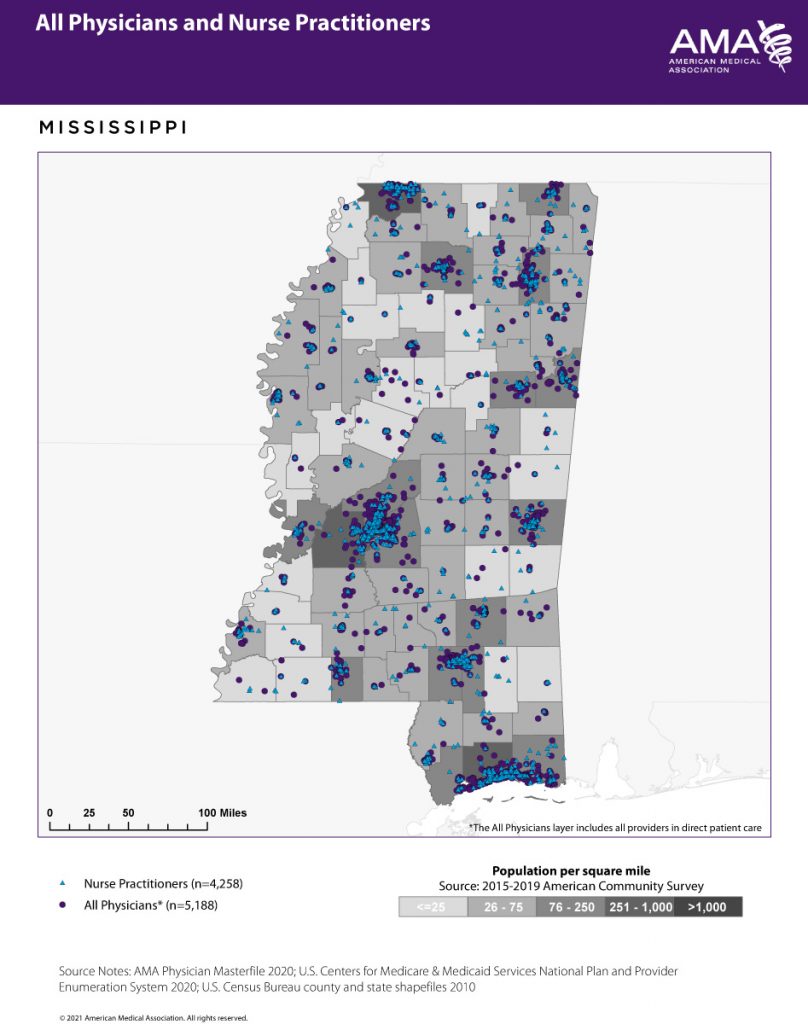

Mississippi may soon have a new class of independent primary-care providers, if the Legislature elects to end a long-standing oversight requirement for its nurse practitioners. The deregulation move would affect more than 4,250 general practitioners across the state, reducing the costs to practice and potentially aiding the state’s widespread primary-care deserts.

State law would no longer require all nurse practitioners to enter into a collaborative relationship with a licensed physician if House Bill 1303, which passed the House on Wednesday, Feb. 3, on a bipartisan 78-38 vote, ultimately succeeds. The legislation would sever the state mandate that requires a relationship with a physician paid to review 10% of a random selection of a nurse practitioner’s cases each month—or 20 total, whichever is less—to guarantee a quality standard of care.

In place of the contractual obligations, new nurse practitioners—and other advanced practice registered nurses, all of whom have the equivalent of a master’s degree in nursing—would instead have to complete 3,600 “transition to practice” hours, during which they would still require the oversight of a licensed physician or trained nurse practitioner. After that period of time, nurse practitioners would be allowed to start totally independent practices, with no further direct oversight, much like any licensed physician.

Rep. Donnie Scoggin, R-Ellisville, the author of the bill and himself a nurse practitioner, told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview that independent nurse practitioners could alleviate some of the state’s critical health-care needs.

“Throughout the country, it is overwhelmingly supported and popular that this is happening. With Mississippi being one of the most unhealthy states, if not the most unhealthy, it just makes sense to allow nurse practitioners to have full practice authority,” Scoggin said.

Dr. Claude Brunson, executive director of the Mississippi State Medical Association, which represents Mississippi’s physicians, has a distinctly different opinion.

“By not requiring some sort of quality oversight, you will end up with two standards of care. With Mississippi being one of the poorest and most rural locations in the country, it’s not OK to say Mississippi will have two standards of care,” Brunson told the Mississippi Free Press on Feb. 4.

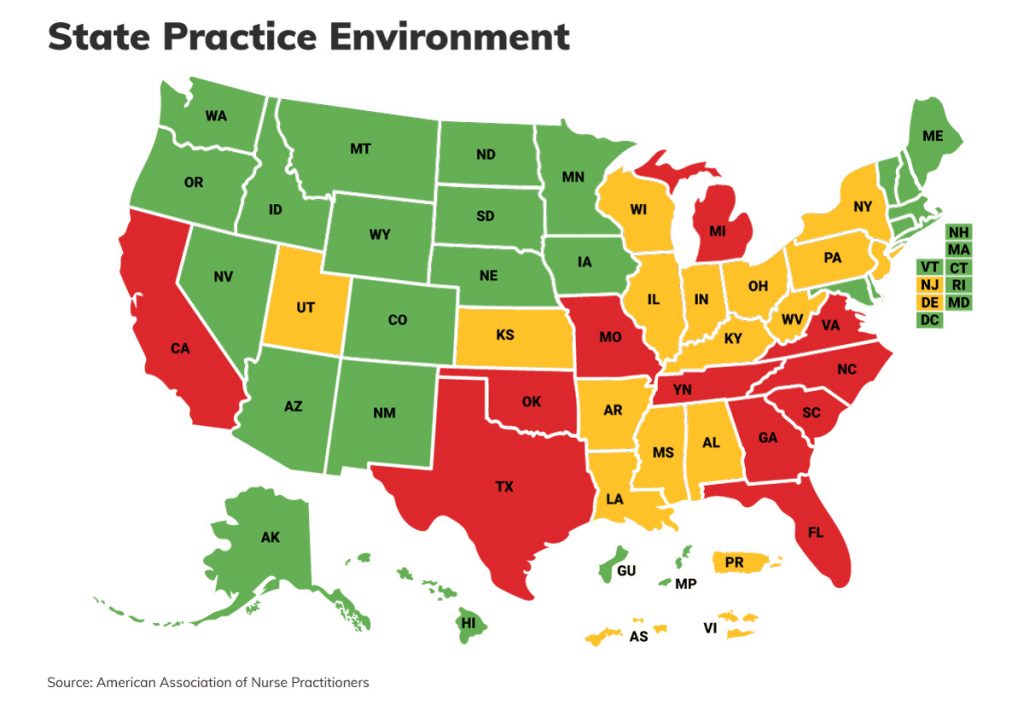

Almost half of U.S. states allow nurse practitioners a full scope of practice, but Mississippi would be the first state in the South to allow for their full independence.

‘It Doesn’t Cost A Dime’

At the heart of the dwindling relationship between Mississippi’s physicians and nurse practitioners are two questions: access to health-care and quality of outcomes.

Adam Clay, FNP-C, is a nurse practitioner in Tupelo. He is eager for the state to free his profession from the collaborative obligations he sees as a needless bureaucratic burden for providers. Without them, he asserts areas starved for health care would see more clinics opening.

“Ninety-one percent of counties in Mississippi have a shortage of primary care. It’s worsened as community hospitals have closed,” he told the Mississippi Free Press on Feb. 3. “We (can) expand access to care, and it doesn’t cost the taxpayers a dime.”

Scoggin has relatively straightforward reasoning as to how nurse practitioners improve access to care. The average salary for the position is significantly less than that of a licensed physician. In areas of the state with few available patients, there exists room for nurse practitioner-run clinics that could not support the higher salary of a doctor.

“A nurse practitioner can open up a clinic in rural Mississippi and take care of a population that is currently being underserved for less than what a physician typically makes,” Scoggin said. “Physicians might not want to go to a rural, underserved area and see a smaller, poorer population because of the lack of funds.”

But collaborative contracts cut into those margins, he added: “It’s an administrative burden, at the end of the day. It amounts to a pay to play. In a state that values right to work and freedom to work. It does nothing to improve outcomes. It hinders access.”

Dr. Jennifer Bryan, chairman of the MSMA board, challenged the assertion that severing the collaborative requirements would meaningfully expand access.

“If you remove the doctor from the nurse practitioner, their appointment scheduling doesn’t double. They don’t become magic, able to see triple the patients. All you’ve done is decrease the quality of care that nurse can provide by removing the expert oversight,” Bryan told the Mississippi Free Press on Feb. 2.

‘Held Hostage’

The present debate over independent practice takes place on long-troubled ground. Physicians fear degrading medical standards and a lack of respect for the expertise, rigor and investment of medical school. Nurse practitioners struggle with ugly, poorly conceived stereotypes of their profession and what they see as a power imbalance relative to physicians.

Scoggin says that while the majority of physicians and nurse practitioners have strong, effective partnerships, the arrangement exploits others.

“There are some that are basically being held hostage. The (physician) that signs the contract says ‘you either do what I say or you can’t practice.’ The problem is once a nurse practitioner has invested thousands of dollars to build, staff and equip a clinic, they’re pretty much obligated to get that contract signed,” Scoggin said.

Advocates for the independence of nurse practitioners interviewed for this story uniformly stated that the educational and training requirements provided for enough clinical experience to allow nurse practitioners to safely practice medicine without oversight.

Scoggin estimated that a truly independent nurse practitioner under the new law would have a minimum of 4,000 hours of clinical experience, including time spent in nursing school, working as a nurse, and completing the transition-to-practice hours.

“Generally, it is my understanding that family-practice physicians, when they get ready to graduate, have had about 4,500 hours in clinical experience in their residency program. That’s going to make the clinical hours relatively equal between the nurse practitioner and the family physician,” he said.

Standardized Education

Dr. Bryan, who has vocally lobbied against the bill, rejects not only those numbers, but their framing as well.

“An (independent) family doctor starts at 10,000 hours and goes up from there,” she said. “ … But it’s a different model of training. Residency is about diagnosis and assessing what’s going on with patients. You’re talking about shadowing hours behind a doctor.”

Bryan’s numbers are replicated in data from other physicians’ organizations, which present a more significant estimate of clinical hours before a physician may practice independently.

Bryan does not doubt that there are many talented nurse practitioners in Mississippi. But she does not accept an alternative to a standardized medical education.

“Across (the U.S.), medical schools are standardized in how they train doctors and how they graduate them. With nurse practitioners, there is minimal standardization of their education. They have a lot of diploma mills around the country. There are some really good schools,” Bryan said, “then there are some not so good schools.”

In response, Scoggin said state nursing-board accreditation standards were satisfactory to ensure a quality education for nurse practitioners. Additionally, he said, national standards did not apply to physicians who studied outside the U.S. “You could go to medical school in Jamaica, you could go to Iran or Iraq,” he said.

Missed Diagnoses

Not every position on the independence of nurse practitioners matches the discipline of the person asked. Monica Carter, FNP-C, is a nurse practitioner at the Holcomb Clinic in Grenada, Miss.

Carter has seen the research examining care quality and access in states with independent nurse practitioners, and though she acknowledges that there are benefits, she is deeply skeptical that deregulation is the right way to go.

“A 2018 study showed that, yes, the access could be helped. But the patient’s (outcome indicators) are not related to the expansion of the nurse practitioner’s scope of practice,” she told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview.

That’s not good enough for Carter. She needs concrete evidence that any significant change to standards of care would drive real improvement in patient outcomes. “To me, that’s the most important issue: the patient,” she said.

Carter’s practice, which includes work in under-resourced areas in the Delta as a Rural Health Care Clinic, is mostly focused on internal medicine and cardiology. When she explained her reluctance to sever the collaborative requirements, diagnosis was again the key topic.

“Let’s say a patient has very high triglycerides,” Carter said, referring to a kind of fat content in the bloodstream. “A knee-jerk reaction from a new nurse practitioner might be to start them on Fenofibrate,” a drug that treats high lipid levels.

“However, they didn’t check an A1C (a blood sugar test) for diabetes. They’re missing one of the main diagnoses that would cause other organ damage. Also, they’re giving them a medication they might not need,” Carter explained.

Carter considers over-medication to be a serious problem, especially in Mississippi, a leading prescriber of pain medications per capita in the U.S. But how often has she encountered that specific scenario—a key diabetes diagnosis missed for a narrower treatment of high triglycerides? In her office, she has caught the missed diagnosis multiple times, Carter said.

Scoggin responded with skepticism that the present system could prevent such oversights. “If a nurse practitioner is going to be out in a clinic by themselves, they need to be accountable. They need to know what’s going on. I don’t know that a retrospective chart review by a physician three months down the road is going to help with that,” he said.

“Right here at the Hattiesburg Clinic, the number-one accountable care organization in the country … (they) found that nurse practitioners over-ordered tests because it was more difficult for them to get to the diagnosis. They found that patients who were being taken care of bounced back to the emergency rooms more often,” Brunson responded.

Scoggin had not seen the Hattiesburg Clinic’s study, but asserted that national data supported the quality of nurse practitioner care. “I can tell you from peer-reviewed journals that (this) does not go along with the information we’ve seen,” he said.

Negotiations At Standstill

H.B. 1303 represents a permanent end to a collaborative system that neither party is entirely pleased with. But the state’s physicians’ associations see the mandatory relationship between nurse practitioners and doctors as salvageable, and necessary for top-quality care. Representatives of the state’s nurse practitioners, on the other hand, assert that collaboration will still happen—on equal terms.

But the requirement to collaborate they see as one more insult to their value. “I think we’re exploited by the whole system,” Clay said. “(For example,) reimbursement for Medicare (pays nurse practitioners 20% less) than physicians. But I’m still required to provide that same standard of care.”

Brunson has little tolerance for the argument that the cost of collaboration justifies an end to physician oversight.

“If that’s an issue, why haven’t you sent in a complaint to the (Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure)? If the problem is the fees, introduce legislation to address the fees. It’s made to sound like it makes sense, but when you drill down it does not,” he said, audibly frustrated.

Scoggin shares Brunson’s irritation, though it may be the solitary moment of accord between the two. “I have sat down with Dr. Brunson and Dr. Bryan and discussed these issues with them. They were adamantly opposed to any negotiation to try and resolve the issue. There was no collaboration at all between the three of us,” he said.

In Scoggin’s eyes, the issue is almost a moral imperative. “The question is the greed,” he posited. “There are physicians who are not doing the bare minimum, or charging an exorbitant amount of money.”

Senate Debate Ahead

Beyond the professional dispute between nurse practitioners and physicians, an ideological undercurrent pulls the debate toward deregulation. Dana Criswell, R-Olive Branch, is a pilot, not a nurse practitioner. But he has signed on to H.B. 1303 because he sees it as good health policy.

“We complain a lot about rural access to health care. It’s historically been Mississippi’s fault because of that lack of access,” Criswell told the Mississippi Free Press on Feb. 1. “Whether it’s certificate of need laws that limit the number of hospital beds, limit the number of clinics—or laws like this that make it difficult for someone to to provide health care. The answer that everyone wants is just ‘let’s pile on more money.’ But it’s really our ridiculous laws that have created this problem.”

“The oversight comes, I think, from the patient. I’m a guy that believes in everybody’s personal responsibility.” Competition in the marketplace, Criswell added, was the best way to improve the quality of care.

The bill is now in the hands of the Senate, where debate is expected to be far more substantial than the quick passage it encountered in the House. Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann acknowledged in a Feb. 4 press avail that he had yet to study the issue himself. But he was sympathetic to the cause.

“I have received comments (from) individuals that were concerned that the review process is expensive and less than adequately functioning,” Hosemann told the Mississippi Free Press. “We’ll be delving into that.”

Contributing Reporter Erica Hensley contributed to this story.