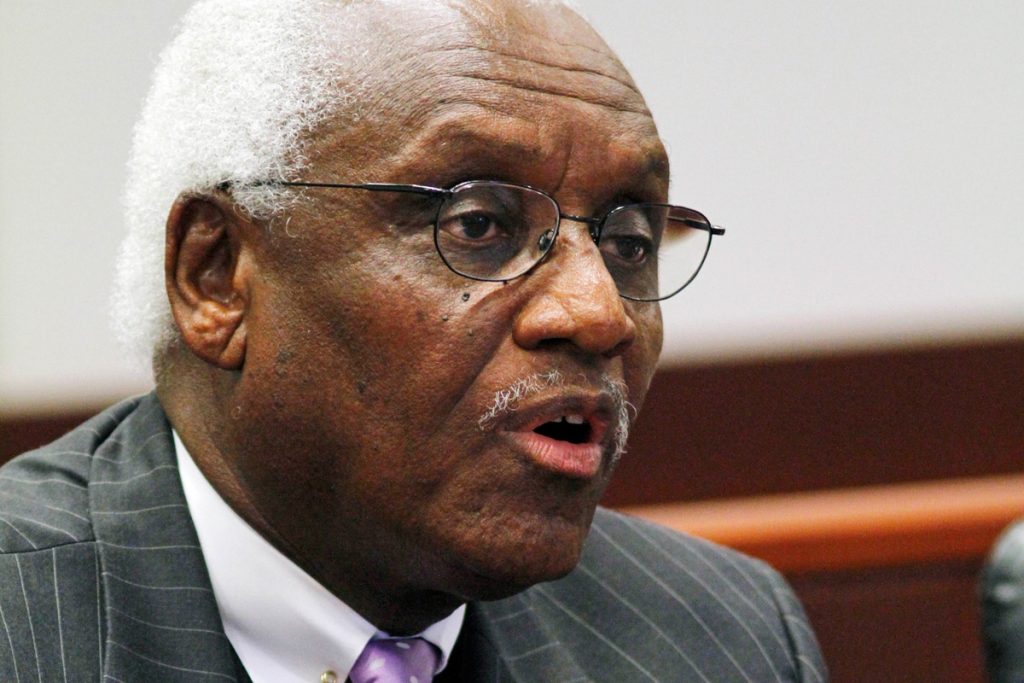

Dr. Cora Norman was a party person. Over the decades she would organize small gatherings at her apartment in Mississippi’s capital city—and she would always do something radical. “She would invite Black and white people,” 80-year-old Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore, a Black civil-rights veteran, says of his long-time friend’s always-integrated gatherings.

There was one aspect of the party, though, that McLemore was excluded from: the Scotch drinking. “I was a bourbon drinker,” he jokes. “So when a lot of people left the party, the Scotch drinkers stayed, and she brought out another bottle that was better than the first.”

McLemore remembers a woman who he says believed in “the loving society,” even when the segregated Mississippi of her day often did not reflect it.

“People loved Cora,” McLemore recalls. Despite her petite stature, McLemore insists that it was “virtually impossible to say no to her.” Norman directed her persistence at disparate groups of Mississippians, using her powers of persuasion to bring together groups who had once entered buildings through different doors and sat in separate sections of city buses.

“In spite of all the difficulties we face, we would face taller mountains still if not for the life and work of Dr. Cora Norman,” McLemore asserts.

Dr. Cora Norman died at age 94 on Jan. 11, 2021.

Diversity in the Boardroom Not Enough

Leslie Burl McLemore is well-acquainted with the “mountains” of which he speaks, as he and Norman began their work in racial reconciliation in Mississippi during the early 1970s—a time when the state was plagued with racial unrest and injustices, having just begun the desegregation of its public schools in 1970. Civil-rights leaders across the state took these first steps towards equality under the long shadow of the Confederate emblem that flew above every public building from the Gulf Coast to the Delta.

When confronted with this single most contentious issue—race—state leaders paid a call to Norman and asked her to become the first executive director of the Mississippi Humanities Council in 1972. The Arkansas native, who had graduate degrees in chemistry and education administration, looked up “humanities” in the dictionary at the end of the call.

The definition that Norman found in her private perusal of Merriam-Webster was a simple one: “the branches of learning (such as philosophy, arts or languages) that investigate human constructs and concerns and social relations.” This definition, coupled with her subsequent conversations with like-minded leaders across the state, was enough to convince Norman of the organization’s importance in Mississippi life. She accepted the role that day and every day until she retired in 1996.

Dr. Stuart Rockoff, the Mississippi Humanities Council’s current executive director, says that the definition that Norman encountered before accepting the job has been permanently altered and expanded by her work in the field.

“She knew the council had to serve all of Missisissippi,” Rockoff says of Norman’s early work.

Norman attempted to ensure that this need to serve and to represent all Misissisppians was reflected in the composition of the board itself, and Rockoff believes that the numbers bear this out as the Mississippi Humanities Council has had Black Mississippians on its board since its founding.

But diversity in the boardroom was not enough for Norman, and she began convening statewide panels and forums to promote the humanities and what the study of the field could do for race relations in the state. This encouraged the state’s humanities scholars to give their academic work real-life application by connecting small-town Mississippians to professors and other civil-rights advocates.

“She insisted on the participation of Black and white people in all of her programs,” McLemore recalls. Though he noted that some naysayers at the time said that the mix of races and genders on the panels was “contrived,” McLemore dismissed such ideas by saying that Norman fostered important conversations that reflected the state’s actual-but-often ignored diversity.

Discrimination Hit Home for Norman

The only child of Robert and Jewel Garner, Norman was raised in rural Arkansas, but she would eventually leave her Columbia County home to attend medical school at the University of Arkansas. During her time there in the mid-1940s, Norman became all too familiar with the high cost of ignoring diversity, as she later left the institution due to a lack of finances and the discrimination she faced as a woman in a predominantly male student body.

Norman would later return to graduate school after marrying her husband, Bill Norman—this time as a student at the University of Mississippi in the 1960s, juggling the demands of two children with her schoolwork. During her time in Oxford, Norman again witnessed the ugliness of discrimination, as she watched the 1962 riots over the admission of James Meredith unfold on her own college campus.

McLemore says that Norman’s creation of what he calls a “Mississippi dialogue” reminded him of the work of NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers, who was assassinated in Jackson in 1963. “He developed a network of chapters throughout the state,” the former Jackson State professor says. “People got a chance to know each other. He connected small towns.”

Norman led this connection for Humanities Council members, bringing humanities teachers and thinkers together throughout the state regardless of their university affiliation. McLemore observes that he made relationships across the state because of Norman’s influence, citing MHC colleagues at the University of Mississippi, Alcorn State and Mississippi Valley State University.

“Cora forced us to talk about race, about economics, about Mississippi. We had not had these conversations before,” McLemore notes.

He believes that this single-minded focus on conversations around the real Mississippi of the time earned Norman a place among Mississippi’s greatest civil-rights crusaders. “She didn’t have Governor William Winter’s name recognition because she didn’t have his visibility, but in terms of basic relationships in our state, she did more than any one person,” McLemore says of his friend.

The Professional Becomes Personal

This dedication to basic, grassroots relationships was true in Norman’s personal life, too.

Rockoff remembers his 2013 brush with a Cora Norman function as nerve-racking. “I heard from Cora that she was coming to Jackson, and she invited me to lunch,” Rockoff says, recalling his feelings of apprehension and excitement at sharing a meal with the giant who had first occupied his seat.

When he arrived at what he assumed would be a two-person lunch between colleagues, he instead entered a room filled with 25 people, all waiting to meet him and to hear about his vision for the Mississippi Humanities Council.

“I realized I was on the spot,” Rockoff says with a laugh. “They wanted to hear about how I planned to continue the work. It was a powerful experience, and I learned how powerful the (Humanities) Council was.”

Work Continues through MHC, Teachers

Norman’s work is ongoing in Mississippi, as Rockoff and his team continue to prioritize the dialogues that Norman started almost 50 years ago.

“Our goal is always to bring a depth of understanding to a subject, so it isn’t just a political debate,” Rockoff says. “Not being afraid of the issues and pushing the envelope is our way of doing our work, and that was established by Cora.”

Humanities professors across the state continue to push the envelope with their own teaching, and Mississippi Humanities Council’s Teacher of the Year Christian Pinnen is no exception. “The humanities are a pathway to understanding the ‘whys’ of our society,” the Mississippi College history professor says.

“The risks Dr. Norman took (with the Mississippi Humanities Council) became the conscience of the state, and the humanities can still play that same role. It teaches people how to ask questions that lead to answers and how to accept complicated answers. We might not know (an answer) yet, but the study of humanities is about being willing to go look for the answer.”