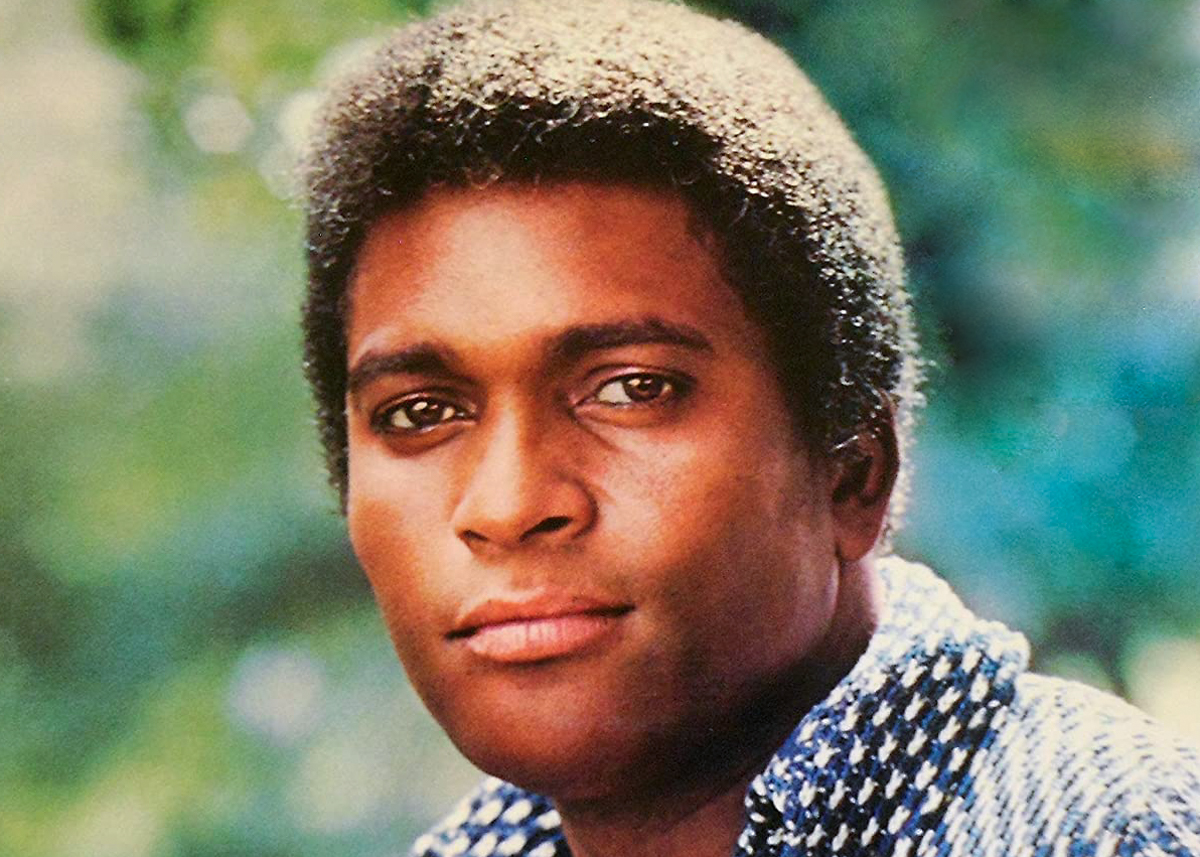

Charley Pride, the most famous son of Sledge, Miss., has died of complications from COVID-19 at age 86. He was a country-music trailblazer who became the genre’s first Black superstar, scoring 29 No. 1 singles between 1969 and 1983.

Though the timing of Pride’s illness is uncertain, his death comes a month after the artist appeared at the Country Music Awards to accept the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award. Variety reported that the event was “the first big COVID-era awards show to test positive for a live audience.”

Variety reported that the audience included about 100 people—far less than the normal crowd of 15,000. The CMA’s executive producer and CEO told Variety that they took a number of steps to make the awards show safe, including not giving anyone credentials “until we had their test result back.”

Public-health officials, including Mississippi’s own state health officer, have repeatedly warned in recent months that, due to COVID-19’s incubation period and the possibility of false negatives, getting tested before attending an event or gathering does not ensure safety. Before the Nov. 11 show, five performers dropped out because they or someone in their circle had tested positive, the magazine reported.

Mickey Guyton, one of a number of Black country artists who have since followed and expanded the trail Pride blazed, expressed sadness over his death in a tweet today.

“We need answers as to how Charley Pride got covid,” wrote Guyton, who last month became the first Black woman nominated for a Grammy as a country solo artist for her song, “Black Like Me.”

“We must protect the elderly as much as we can from Covid. Please please please look after each other,” she added later this evening.

Country star Dolly Parton, who has recorded music with Pride in the past, also honored the star on her Twitter account today.

“I’m so heartbroken that one of my dearest and oldest friends, Charley Pride, has passed away. It’s even worse to know that he passed away from COVID-19. What a horrible, horrible virus. Charley, we will always love you,” wrote Parton, whose $1 million donation earlier this April helped Moderna create its upcoming COVID-19 vaccine.

‘Cotton Picking Delta Town’

Charley Pride, a 2000 inductee into the Country Music Hall of Fame, leaves behind a storied legacy with art that had an impact worldwide—far beyond the reaches of his Quitman County hometown, Sledge, which boasted around 340 residents the year of his birth and remains home to fewer than 500 today.

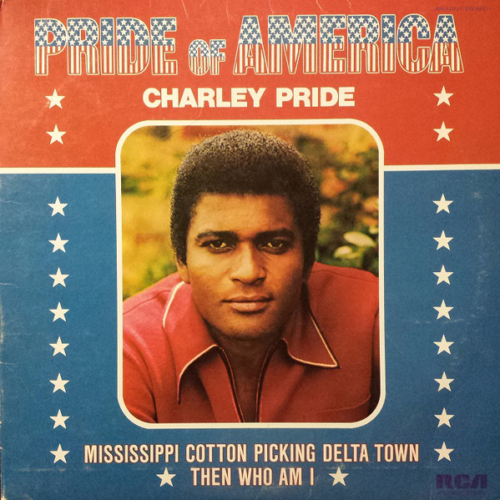

The future country music star was born into a family of Sledge sharecroppers in pre-civil rights Mississippi on March 18, 1934. He sang about life in a “Mississippi Cotton Picking Delta Town” in his 1974 single of the same name, which peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart.

“Down in the delta where I was born / All we raised was cotton, potatoes and corn / I’ve picked cotton ’til my fingers hurt / Draggin’ a sack through the delta dirt,” he sang in the song penned by Harold Dorman and George Gann.

As a grade-school child in the pre-Brown v. Board South, Pride would walk four miles to a segregated, all-Black school while busses of white children passed him by.

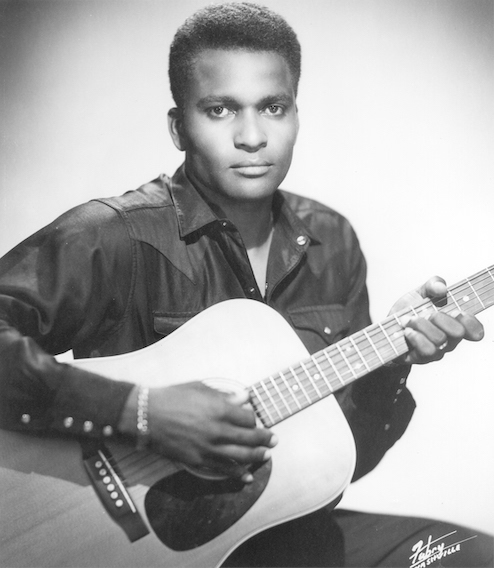

He grew up listening to the Grand Ole Opry on his father’s radio and bought his first guitar with money he earned from picking cotton in his hometown. But young Pride also drew inspiration from Jackie Robinson, who in 1947 became the first Black player in Major League Baseball since the 1880s.

From the Negro American League to Nashville

From 1953 to 1956, Pride played baseball in the Negro American League as a pitcher for the Memphis Red Sox, then the Boise Yankees and later the Birmingham Barons. During long bus rides, Pride would keep his teammates entertained by singing and playing guitar.

During his baseball career, the U.S. Army drafted the future recording artist in 1956, stationing him in Fort Carson, Colo., in 1956. Upon discharge, he rejoined the Memphis Red Sox in 1958, but his professional baseball career foundered after he suffered a throwing arm injury.

Pride took a construction job in Helena, Mt., in 1960, where he joined a local semi-professional baseball team, the East Helena Smelterites. After becoming aware of Pride’s singing ability, the team manager began paying him $10 to sing before each game. Attendance at the games grew, and Pride began playing singing gigs in the area, including with a local four-piece band, the Night Hawks. The group recorded a demo tape with Pride.

When RCA Victor’s Chet Akins heard the demo tape, he offered Pride his first contract in 1965, and Nashville agent Jack D. Johnson, who had helped grow the careers of artists like Skeeter Davis, signed him.

In 2010, country outlaw singer Willie Nelson recalled an incident early in Pride’s career when the Black country singer arrived at a club whose owner, Nelson said, “was a solid redneck” who “didn’t want him to sing there.”

“So I kissed Charley on the mouth. I was just trying to ease the tensions a little bit,” Nelson told Parade magazine in 2010.

Pride’s ‘Permanent Suntan’ Shocked Fans

After his first early singles, Pride scored his first big country hit with “Just Between You and Me,” which rose to No. 9 on the country charts and earned a Grammy nomination. But the singer’s label released his singles with no photographs on the covers of the 45 r.p.m. records devoid of any information about his background.

When 10,000 country-music fans whom he had won over with his music showed up at his first big show at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium in 1966, rapturous applause trickled off into stunned silence as it dawned on them that the man who had just walked onto the stage was Black.

“Friends, I realize it’s a little unique, me coming out here—with a permanent suntan—to sing country and western to you,” he told the audience, words memorialized in the liner notes to his 1981 album, “Country Music: Charley Pride.”

“I am from Mississippi, my daddy was a farmer down there. And I sing country music. I want to entertain you if you’ll let me,” Pride told the crowd.

In 1967, Pride became only the second Black artist to become a member of the Grand Ole Opry since DeFord Bailey, a harmonica player, who performed at the Opry from 1925 to 1941. Pride was also the first Black artist to perform since Bailey left the Opry.

Two years after Pride’s first performance at the Opry, Linda Martell, a Black woman famous for her hit, “Color Him Father,” performed at the Opry in 1969. Since Pride, though, the Opry has only admitted one additional Black member: country singer Darius Rucker, who joined in 2012.

In 2008, weeks before the United States elected its first Black president, Rucker became the first Black artist to score a No. 1 country hit since Pride decades earlier.

“My heart is so heavy. Charley Pride was an icon, a legend, and any other word you wanna use for his greatness,” Rucker tweeted this evening. ” He destroyed barriers and did things that no one had ever done. But today I’m thinking of my friend. Heaven just got one of the finest people I know.”

Pride, Wife Faced Racism in Montana

But even in Montana and as a budding star, Pride and his wife, Rozene Cochran, encountered racism. In an Aug. 2, 1967, report titled, “Nothing to Be Smug About,” Cochran told The Helena Independent Record, a Helena newspaper, that she and Pride “were refused service in a Helena restaurant and a real estate agent refused to show them a home,” the paper reported.

“Montana doesn’t have a racial problem, but that’s not saying it wouldn’t if it had a large enough nonwhite minority,” The Independent Record reported. “There are indications that many Montanans have the same attitude toward nonwhites as white people elsewhere. … Montana does have a sizable nonwhite population in its (Native American) citizens, and Mrs. Pride is more concerned about the attitude Montanans have toward them than their reaction toward Negroes.”

“They’re treated much like Negroes in the South, she says. She told of a white clergyman—a minister of God, mind you—who claimed to be broadminded but acknowledged that he couldn’t tolerate Indians. She told of a white neighbor in Helena who cuddled the Prides’ baby but chased away an Indian boy who came to play with their son.”

In 2014, Pride recalled his life in Montana in an interview with Last Best News.

“Montana is a very conservative state,” said Pride. “I stood out like a neon. But once they let you in, you become a Montanan. When the rumor was that I was leaving, they kept saying, ‘we will let you in, you can’t leave.’”

The family ultimately did leave Montana in 1969, moving to Dallas, Texas.

In the 2019 PBS documentary, “Charley Pride: I’m Just Me,” Pride recalled performing a sold-out-show in Big Springs, Texas, on April 4, 1968—the night of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

“I got onstage, nobody said nothin’,” Pride said. “They applauded, I got a standing ovation. I didn’t say nothin’ about nothin’ pertaining to what had happened. But it was hanging there, what had happened and me the only one there with these pigmentations. You don’t forget nothin’ like that.”

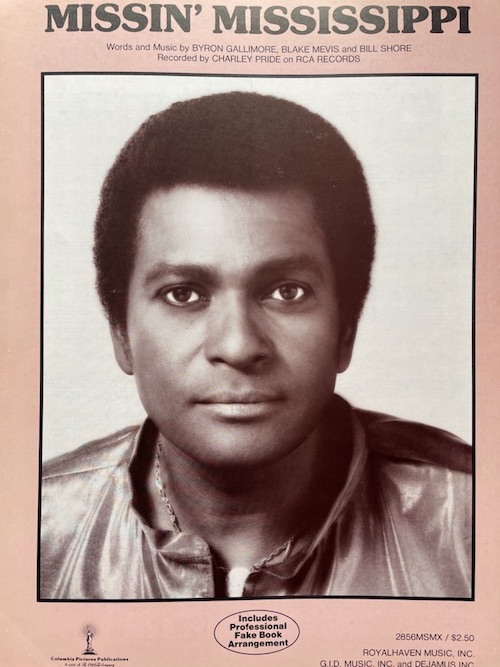

But Pride won the adoration of even the genre’s overwhelmingly white audience with hits like “Kiss and Angel Good Morning” and “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone?” In the 1970s, he became RCA Records’ best-selling performer since Elvis Presley, ultimately scoring 52 top-10 Billboard Hot Country hits between the late 1960s and late 1980s.

In 1971, Pride won the CMA awards for Entertainer of the Year and Top Male Vocalist for “Kiss An Angel Good Morning”—the only song of his that earned crossover success as a Pop Top 40 Hit, where it rose to No. 21 on the chart.

Pride Brought Unity Amidst Ireland’s ‘Troubles’

Pride scored international success, with a 40-date tour package in the United Kingdom in 1975, which drew the attention of Irish music promoter Jim Aiken.

At the time, outside music artists avoided playing in Northern Ireland, where a violent, deadly conflict, known as “The Troubles,” had raged since the 1960s. Thousands died during The Troubles between the 1960s and the 1980s as the mostly protestant Unionists, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the U.K., clashed with the largely Catholic Irish nationalists, who wanted to leave the union and form a united Ireland.

But after Pride’s U.K. tour, Aiken traveled to meet him at a show in Ohio, where he convinced the singer to perform a show in Belfast. Pride performed at the Ritz Cinema in the Northern Ireland city in 1976.

Pride, the son of a state who just over a century earlier had seceded and gone to war against its own union to keep people like him enslaved, temporarily united both sides of the Northern Ireland conflict in praise of his decision to go where few other acts, either in music or sports, had been willing to travel.

One song Pride performed at the show, his 1965 song “Crystal Chandeliers,” became a hit in Northern Ireland, whose residents embraced it as a unity song, and it subsequently became a single there and across the U.K.

Pride’s performance helped bring an end to the effective boycott, Aiken’s son, Peter, told the Belfast Telegraph.

“After Charley, other mainline artists started to follow for Aiken dates even though the Troubles continued,” the younger Aiken, whose father had died seven years earlier, told the newspaper in 2015.

Pride returned to Belfast repeatedly in the years afterward, including in 2015, when he came back to Northern Ireland to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of Crystal Chandeliers’ recording. Belfast Telegraph journalist Eddie McIlwaine, who died in 2019, interviewed Pride for the story.

“Chandeliers is now a popular pub song in Belfast, Charley is delighted to be told,” McIlwaine wrote in 2015 in a story about how “Chandelier Charley Pride lit up (the) whole city of Belfast.”

The journalist, who died last year, recalled a memorable night with Pride and the elder Aiken in 2005.

“(Pride) is, of course, officially, a Nashville legend. One night 10 years ago he was having dinner with Jim and me in a crowded restaurant in Nashville,” McIlwaine wrote. “When he got up to leave the diners rose as one and applauded him to the door. Now you don’t get that at every meal.”

‘Roll On, Mississippi’

Though he spent most of his later life in Dallas, Pride’s connection to Mississippi endured. In 2008, the Mississippi Art Commission awarded him its lifetime achievement award during the Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts ceremony. In 2019, Pride became the first recipient of the Crossroads of American Music Award, which he accepted at the Grammy Museum in Cleveland, Miss.

“Rest In Peace to Charley Pride, a Mississippi great,” Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves tweeted today.

#CharleyPride performed at the CMA’S last month where he received the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award.

He sang his hit “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’” with country singer Jimmie Allen. This is his last performance. R.I.P 🙏🏾 pic.twitter.com/zLbGENTdaD

— Amaka Ubaka (@AmakaUbakaTV) December 12, 2020

Pride paid homage to his home state, and the eponymous river that runs along its western border, in the 1981 top 10 hit “Roll On, Mississippi,” which Pride co-produced. Its lyrics, a portion of which are included below, were penned by songwriters Kyle Fleming and Dennis Morgan and recall, with nostalgic longing, Pride’s childhood in the little Delta town of Sledge.

Roll on Mississippi, you make me feel like a child again.

A cool river breeze, like peppermint leaves,

The taste of it takes me back,

Chewin’ on a straw, torn overalls,

I can’t hold an old straw and muddy river.

Just like a long lost friend.

Roll on Mississippi, you make me feel like a child again

Roll on Mississippi, big river roll.

You’re the childhood dream that I grew up on.

Roll on Mississippi, carry me home.

Now I can see I’ve been away too long.

Roll on, Mississippi, roll on.