My dad and his twin brother were born in a sharecropper’s shack in the summer of 1948. Nobody knew they’d be twins; if the family didn’t have indoor plumbing they for sure didn’t have prenatal care. They were the last two of four living children born to Frank and Etta Lee. Frank had a fourth-grade education, which was more than Etta Lee had. They would be the last of a long line of poor white farmers in the Arkansas Delta.

In 1951, my grandparents heard about better work from some migrant cousins, packed up and moved to Indianapolis for a job in a brass-pipe factory, the move that would change trajectories for generations. Grandpa joined a union, went to work inside and qualified for a FHA loan.

He and Etta Lee bought a house, 900 square feet with an indoor toilet for the first time in their lives. The kids didn’t have to chop cotton again. They all graduated from high school and stepped up some big rungs on the American Dream ladder. They owned diners, managed factory floors and became a sheriff’s deputy. Their kids, my cousins, built on those foundations as a Marine, Airman, nurse, educator, firefighter, manager and more.

My dad joined the Army, learned to fly helicopters, went to Vietnam, and came home with two purple hearts. He made his way back to the Delta and learned to fly crop-dusters, then joined his uncle dusting cotton fields over north Alabama. My mom met him while she was working at a department store when she was in college.

This is where it gets good for me. They got married, and I was born in a hospital, not in a cotton field.

But they took me home to one, a trailer out by his little grass airstrip. Pretty soon, he took a job in southwest Arkansas, flying helicopters for forestry, spraying for bugs, fighting fires and tending to thousands of acres of timberland.

Cotton Fields to Court Houses

When I was 8, we moved to Columbus, Miss., my beloved hometown. My dad flew helicopters over timberland. My mom taught English. I loved school and wanted to be a fighter pilot, but my eyes were too bad. Along the way, my devotion to my dad and his stories developed into real interest in war, then history, then politics, then law, all covered up in the literature and stories my momma gave me year after year. Those stories and storytelling were my foundation going to college.

I wasn’t the first person on my paternal side to graduate from college, from Harding University, not too far from that old sharecropper’s farm. I was the second. My cousin Kelley—more on her in a bit—beat me by two weeks. I went on to law school at Vanderbilt and met Jennifer Duck from Chattanooga who was in grad school at Tennessee.

She and I began our married life in Tupelo where I started practicing law. We soon moved to Jackson, making good money, paying off student loans, having babies. Jenn finished grad school at Southern Miss. I love being a lawyer, but, like my mother before me, I found my big adventure being a teacher. So when our girls were little, we moved to Montgomery, Ala., where I became a young law professor.

Montgomery is a very special place for a liberal, feminist, Christian southerner to thread the code-switching needle to teach law at a Church of Christ university in a scrappy law school founded in the 1920s by a segregationist judge. We had a good time, but eventually, we seized the classic, cliched American opportunity to move west, breaking some family hearts when we struck out to California. One of my first students in Los Angeles was from Decatur, Ala., and he sensed my early culture shock.

“Oh, Professor, don’t worry. There are so many southerners out here we call it Malibama,” he told me.

So now we’re rearing our teenage daughters on Pacific Coast Highway in a condo with an ocean view. They have no hint of southern accents. They’re all California: Gen Z Marxist vegetarians; brilliant, creative, compassionate, activist kids embracing all the rich colors of this county with 10 million souls speaking 180 languages on the doorstep of the whole world.

They’ve played Carnegie Hall with their public high school orchestra. They love K-pop. They’ve demonstrated with Black Lives Matter and the Women’s March.

I get to teach and practice law with clients and partners on six continents and travel routinely to the world’s great cities. It ain’t the trailer in a cotton field. By every measure, it’s the mythic American dream, a family rising over four generations from a sharecropper’s shack to a home above the sparkling Pacific with educational and professional resources to launch our kids wherever they want to go.

‘Racism Is National Suicide’

America seems to be working as designed, but here’s the fatal flaw. Our American dream rests on something subtle and pernicious. Remember that pivotal move to Indianapolis in 1951? The union job, the FHA mortgage, the house and the public school, the crux of a family’s history changing the lives of four kids, their nine kids, 16 grandchildren?

That union job and its attendant post-war FHA loan were only available to white men.

In the 1950s, the national policy was to empower people—white people—to own homes and begin to generate wealth through real estate and banking. It worked. Those homes were out in the suburbs, moving folks out of crowded urban centers and off the farms where they had rented for decades, setting up new communities, new neighborhoods, new schools.

The U.S. made decisions along the way to fund public schools by local property taxes, so new, thriving, appreciating homes funded new, thriving, appreciating schools, sparking a positive cycle of prosperity, generation over generation. But for Black people those programs left families stranded in arid economic droughts without ready means to buy homes, move to the suburbs, or fund good schools, left in neighborhoods where they had to rent, where property taxes fell, where schools suffered, grinding out a negative cycle of poverty.

White flight only accelerated the cycles in panicked reaction to Brown v. Board of Education. Folks didn’t start establishing all those private academies in 1955, with an explosion in of them in 1970 after a certain Supreme Court decision, by coincidence.

Of course, there’s no single story. Not all white folks thrived, and many Black folks sparked their own cycles of wealth and prosperity in defiance of the obstacles set against them. But the operating systems behind our economies rest on some very specific, intentional decisions reflecting a certain vision of American values.

Those systems worked for my family in astonishing leaps of prosperity and opportunity. Those same systems stymied similar opportunities for generations of Black families, giving us poor white folks a massive head start into cycles of prosperity. The abject waste in these racist decisions creates a poverty for all of us. What have the United States squandered by denying poor, uneducated workers the opportunity for a job, a loan, a home, and good public school, just because they weren’t white?

Racism is national suicide.

Plot Twist: Inheriting the American Dream

Now, here’s the plot twist in the Bakers’ rich American saga, a comeuppance to redlining. My cousin Mike and I are the only male offspring of the brothers from our parents’ generation, the last men who would bear the Baker name from our branch. In common patriarchy, the girls would get married and take other names, and Mike and I both ended up with daughters. So for a few years, there was a low-key regret whispered in the family that our Baker name was fading out into other family trees with no male heirs to carry it on.

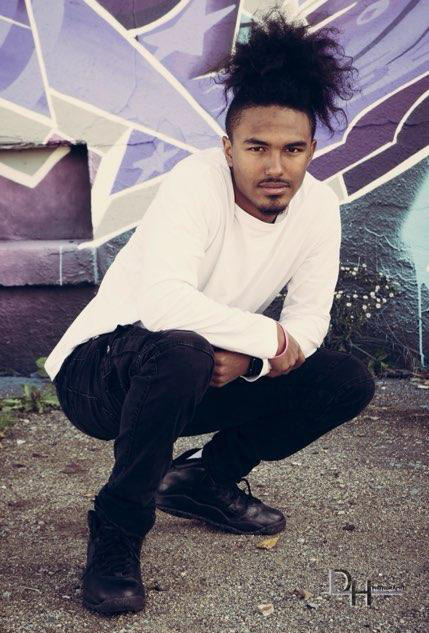

But here comes our beloved cousin Kelley who beat me out of college. She started a family in a nontraditional way. Her son, Keagan, is a Baker, and he’s Black.

In spite of systems designed to promote and protect the wealth and prosperity of white men, as our family history stretches out toward its fifth generation from the sharecroppers’ shack in the Delta, the family goes forward with brilliant artistic kids in the midwest, sharp feminist girls in L.A., and a talented young Black man taking on the world. They are the newest Americans coming of age and planting seeds that will bear astonishing fruit in the next five generations.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.