There is a significant difference between what poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren called our “felt history”—history that lives in the national imagination—and our actual documented history.

In the United States there is history we like to believe as real because it makes us feel comfortable and tells a positive story about the American experiment, which often means it is based in mythology. That mythology can take numerous mutable forms, whether it is the white supremacist notion of the Lost Cause that led generations to deny the connection between the Civil War and the institution of slavery; or perhaps it is the fog of neglect in the decades after World War II when Americans denied or ignored the harm inflicted on Japanese Americans during wartime internment. Whatever shape this myth takes, it leaves out important details about historical events, particularly those that make us squirm in disbelief and disgust when the truth is revealed.

As Warren continues in his commentary on history, “When one is happy in forgetfulness, facts get forgotten.”

Gov. Tate Reeves’ Patriotic Education Fund is based in a felt history that is happy in forgetfulness. This is a history based entirely in a feeling about American history rather than the facts. When a budget recommendation invokes a line of fiery invective—“far left socialist teachings”—as a justification for its existence, you can be assured that it is not a work of education policy developed through a process of thoughtful research and discernment. It is nothing more than a piece of culture war agitprop, an ahistorical fantasy of American history.

The Playbook of Totalitarian Leaders

Reeves’ description of the Patriotic Education Fund is loaded with vague slogans like “American values.” It also describes the need to “combat the dramatic shift in education” without even describing what that shift is. This is not sound education policy, particularly in a state that is in dire need of it. The Patriotic Education Fund is a piece of public policy at odds with the core democratic goals of education, which ideally should encourage students to be open-minded, tolerant and critical rather than close-minded.

This Patriotic Education Fund seems to have its origins in the playbook of totalitarian leaders, who use propaganda, intolerance, and indoctrination to distort facts and create an official history or ideology. Consequently, students in totalitarian states are taught to be docile, obedient and compliant rather than to think critically. Gov. Reeves is the one seeking to indoctrinate students, not the historians who have been looking closely at the American past and questioning the role of slavery in this country’s founding and economic development, examining the history and legacy of Native American removal, or studying the enduring legacy of Jim Crow.

Although I am not a historian, I am a writer and literature professor who uses the work of historians to create narrative stories rooted in the past. From archival research I have done for three books and numerous articles, I know that what historical documents tell us about the past is often at odds with the stories we sometimes tell ourselves.

What I have learned through the years is that there is a great danger in being your own historian, which is why I rely on the work of actual historians in constructing narratives about Mississippi and the southern past. In trying to create the Patriotic Education Fund, Gov. Reeves is seeking to be his own historian, which is fine for him to do personally but is dangerous as policy since it affects an entire citizenry and culture. Policy like this crosses the line into propaganda when it begins to dictate the type of history that can be taught in the state.

How History Differs from Memory

The Patriotic Education Fund is not the first time the state of Mississippi has sought to shape the way history is taught. In 1975 a group of educators sued the state when a state textbook rating board refused to rate the book “Mississippi: Conflict and Change” by James W. Loewen and Charles Sallis as a Mississippi history textbook. The state textbook rating board rejected the book because of its inclusion of African Americans, Native Americans, women, workers, and subjects like poverty, white terrorism and corruption. Instead, it adopted two other books that either refused to confront the legacy of segregation in Mississippi or were sympathetic to the principles of white supremacy long associated with Mississippi. The lawsuit Lowen v. Turnipseed overturned this book ban.

Although nearly 50 years have passed since Lowen v. Turnipseed triumphed, Mississippi students still don’t learn an inclusive story about Mississippi’s history or American history more broadly. This past semester in my class on Southern Memory and Identity at the University of Mississippi, I encountered graduates of some of the best public high schools in Mississippi who had never even studied the history of the Civil War and knew only as much about the Civil Rights Movement as King’s “I Have a Dream Speech. Not a single student had any knowledge of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, Mississippi’s civil rights-era spy agency, despite broad public access to those archives. Nor did they have more than cursory knowledge of the murder of Emmett Till.

In the course of a semester, my goal is to help students learn how history differs from memory, though the meaning created by memory may influence the way we view history. Throughout this semester, the texts for this course confront the idea of southern identity and the inescapable nature of the history of the region, as well as the ways in which cultural memory may exist in segregated cultural spheres. While many students grimace when they see the reading list at the beginning of the semester, by the end of the term they have begun to fill in a few gaps from their high school education, but by no means all of them.

Habitus and Essentialism

While the texts for the semester wrestle with identity with respect to race, region and history, the constant throughout the books we read are the ideas of habitus and essentialism.

By habitus I mean a set of dispositions through which one responds to the world in particular ways without much thought. These are deeply ingrained habits, skills and dispositions we hold as a result of our life experiences. By essentialism, I am referring to the view that certain categories have an underlying reality or true nature that one cannot view directly. It is by essentialism that we ascribe certain characteristics to specific groups. By engaging with these ideas, I want them to understand how cultural identity and memory can be shaped and formed.

On the final exam, I ask students to conclude with a section in which they write about certain readings from this semester as well as how the ideas of habitus and essentialism affected them, or perhaps did not affect them. This year, I was especially taken by what one of my students wrote in reaction to reading an excerpt of Pulitzer Prize winner David Blight’s “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.”

“The truth of historical events have been covered up in most textbooks and even by my teachers, whom I believed would always reveal the truth to me,” she wrote. “This consciousness to protect the minds of younger adults has not only negatively affected the way younger adults view the world, but it has also damaged the amount of trust placed in the education system.”

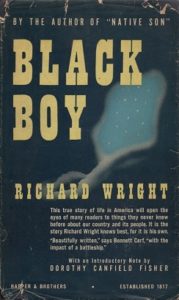

The student continued to discuss how what she described as “manufactured ideas of history” make it difficult to understand the reality of the past, as it was described in Richard Wright’s “Black Boy.”

Gov. Reeves’ Patriotic History Fund is the type of manufactured idea of history my student reacted against. In one form or another, on the final exam each one of my students expressed disappointment at the narrow view of history, cultural memory and identity they had been exposed to prior to my class. While I can see Gov. Reeves viewing me as someone indoctrinating my students, I don’t see reading and discussing the work of distinguished historians, writers, and thinkers like David Blight, Grace Elizabeth Hale, Edward Ayers, Jesmyn Ward, Albert Murray, Lillian Smith and Richard Wright as indoctrination. All I am doing is presenting a wide spectrum of writers and ideas on a topic and encouraging students to discuss and debate them, even disagree with them.

In his classic study of the South, “The Strange Career of Jim Crow,” the great southern historian C. Vann Woodward wrote that “[t]he twilight zone that lies between living memory and written history is one of the favorite breeding places of mythology.” The history that Gov. Reeves proposes to spend $3 million to teach to Mississippi schoolchildren is nothing but mythology, and not even a story about America that can be thought of as real history. This history exists, but only down a dark road in a place Rod Serling once named “The Twilight Zone.” This is not a road Mississippi should venture down, since we already know where it leads.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.