“Really, this whole year has been one big crisis.”

With those words in late October, University of Mississippi Associated Student Body President Joshua Mannery, a senior political science and English double major from Jackson, was not just talking about the pandemic that has upended the world, but was referring to the drumbeat of controversies that the University of Mississippi University has faced this year.

The “crisis,” to use Mannery’s word, is punctuated by a new “climate survey” showing that many marginalized students and faculty members believe administrators do little to support them; 838 individuals reported they had experienced unwanted sexual contact or conduct while at UM; and that more than half of university faculty and staff have considered leaving the public university still officially branded “Ole Miss” in the last year.

Photo Courtesy Joshua Mannery.

Certainly, 2020 has been a test for administrators at the beloved southern university, aside from COVID-19 challenges to safety and enrollment. In July the Mississippi Free Press reported on the backroom deals involving powerful UM alumni that opened the throttle on a plan to glorify a Confederate monument relocated to an old cemetery on the edge of campus. Further concerns about transparency at the college were amplified when MFP reporter Ashton Pittman published a three-part investigative series about the university’s coddling of racism in order to woo certain wealthy donors.

That three-part UM emails series has turned into a nine-part package to date culminating with multiple followup interviews with Black students and professors regarding the climate at the University of Mississippi and their suggested solutions. These UM stakeholders raised those concerns as the university, and former and current deans of the journalism school, where the emails were centered, have refused interviews to discuss plans to address the problems exposed in the reporting package.

Issues revealed in the MFP series included efforts dating back to 2018 to find and punish individuals who exposed information about racist incidents on campus, including the identity of UM donor Blake Tartt who shared photos and video that, once posted on Facebook by UM supporter and donor Ed Meek, led the journalism faculty to push to change the name of the journalism school, but without publicly revealing that Tartt was suspected in 2018 to be involved.

Mannery, the current student body president, wrote an MFP Voices piece with UM Black Student Union President Nicholas Crasta in August, calling for the university to be more transparent about its solutions to problems that are open secrets on campus. Mannery again told the Mississippi Free Press, in an October interview, that UM’s closed-door decision-making and crisis-management style, conducted by select administrators, does not lend itself to establishing trust within the diverse academic community.

“I think moving forward it’s important that they be as transparent as possible,” Mannery reiterated. “And I know they hear that all the time, but the university could absolve itself of a lot of the controversy it finds itself in if it just talked to its constituents, groups, its community more.”

Now, leaders at the university have muddied the waters around the recent campus climate report, choosing to invoke a fierce privacy that seems out of place at a public institution in America. The university has not made the results readily available to the public despite the virtual reveal to the UM community. In contrast, results of campus climate surveys are often made accessible for public viewing at both public and private universities. Stanford, Fordham University and the University of California system are among universities whose climate survey results are fully available, including those who worked with the same consulting firm UM used.

A source provided the Mississippi Free Press with a full copy of the UM climate study results.

Sorted by Racial Identity, Comfort Levels

During the spring 2019 semester, the University of Mississippi drafted a contract with Rankin and Associates Consulting, a Pennsylvania firm that specializes in what its website describes as “assisting educational institutions in maximizing equity through assessment, planning and implementation of intervention strategies.”

Administrators at the university intended to measure what Dr. Sue Rankin of Rankin & Associates calls “campus climate.” Rankin defines campus climate as “the current attitudes, behaviors, standards and practices of employees and students of an institution.”

The university subsequently formed the Climate Study Working Group, which consisted of administrators, faculty, staff and students. This work group paired with Rankin and Associates to administer the survey during the fall 2019 semester—a year after the Ed Meek controversy first racked the university.

The University of Mississippi released a summary of the results during a virtual presentation on Sept. 22, 2020, but the detailed final report is only available to those with UM login credentials.

The response rate for the survey was listed at 24.4% in the executive summary of the report.

The results from the response pool paints an intimate portrait of a school grappling with some of the most serious issues that institutions of higher learning face today.

The results summary, over all, appears positive for the university. In total, 5,538 surveys were returned for analysis. Of those respondents, 3,229 were undergraduate students, 854 were graduate students, 616 were faculty members, and 839 were staff.

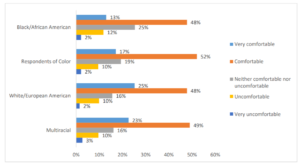

Seventy-one percent of total respondents felt “comfortable” or “very comfortable” with the social climate at the University of Mississippi.

Respondents were sorted by racial identity. Seventy-three percent of white respondents reported feeling “comfortable” or “very comfortable,” while 12% felt “uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable” with UM’s social climate. Fifteen percent of white respondents reported experiencing hostile or exclusionary behavior, with 8% reporting it was on the basis of racial identity.

The data within the full report show that respondents belonging to minority or marginalized groups did not report the same levels of comfort as heterosexual white respondents, however.

Sixty-one percent of Black respondents reported feeling comfortable or very comfortable with the climate at UM, but 14% of Black respondents reported feeling uncomfortable or very uncomfortable. Fifty-three percent of Black respondents who experienced hostile or exclusionary conduct reported that they believed it was on the basis of their race.

ASB President Mannery witnessed the virtual reveal of the climate-survey results. He told the Mississippi Free Press that the experiences marginalized respondents reported did not surprise him.

“To a certain extent I think a lot of people on this campus, regardless of who they are—students, faculty or staff—experience the same thing, which is a university that is definitely at odds with itself a lot of the time,” Mannery said. “I just think you really feel that lack of direction and vision and community a lot of the time.”

Sexual Predator: ‘Highly Revered’ with ‘Significant Power’

Sexually violent crimes are more prevalent than other crimes on college campuses. A 2007 study on campus sexual assault showed that 19% of women reported being sexually assaulted during their time at a university while 5% to 6% of males experience sexual assault while at college. The University of Mississippi’s survey results indicated that the school, known across the nation for its raucous atmosphere and season-long bacchanals, had many of the same problems.

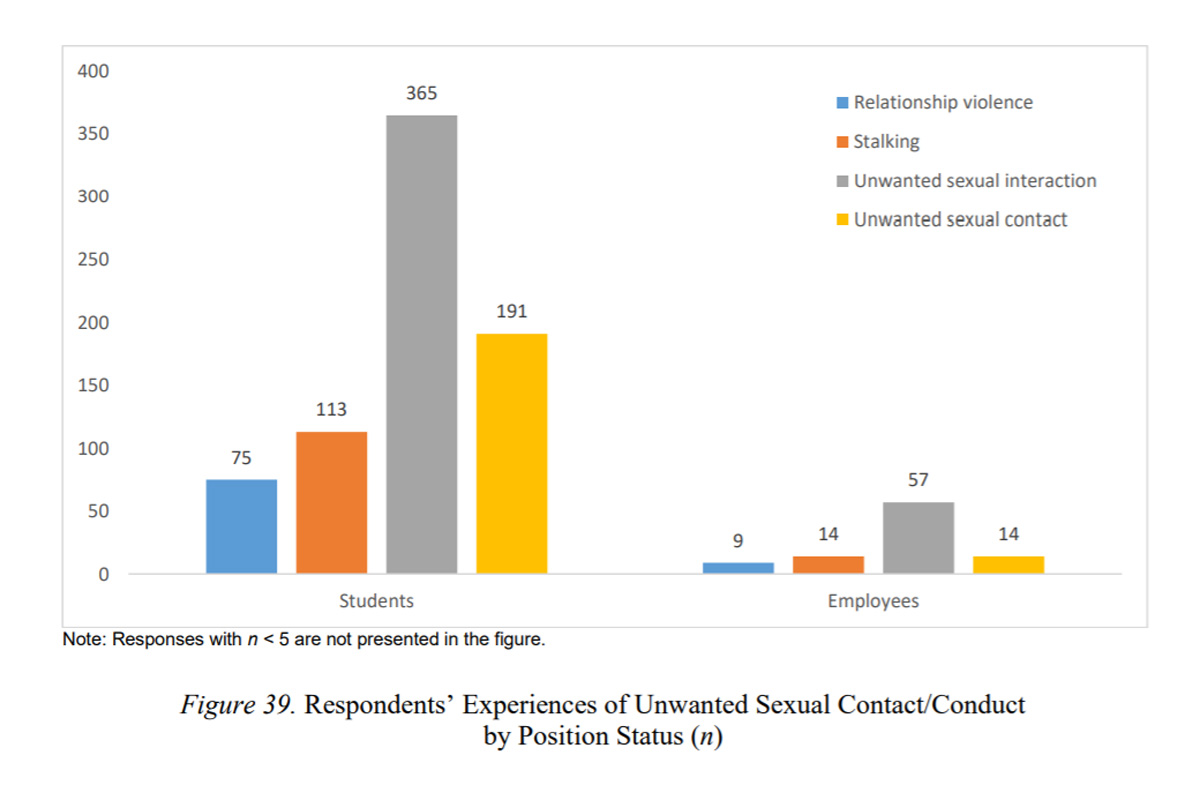

Fifteen percent of UM respondents, or 838 individuals, asserted that they had experienced unwanted sexual contact or conduct while at the university. These instances of abuse occurred across the Oxford and UM community and were present in both student and staff populations. Four percent, or 205 respondents, reported experiencing unwanted sexual contact during their time at UM, which included acts of fondling, rape, sexual assault and penetration without consent.

Two percent of these respondents reported that they had experienced relationship violence and stalking. Eight percent experienced unwanted sexual interactions, which includes repeated sexual advances, catcalling and sexual harassment.

The majority of respondents did not report their experiences with sexual assault or abuse, listing several reasons. Many feared retribution or not being believed. One respondent wrote: “The Faculty member was highly revered and had significant power in the community. I was afraid that reporting the incident might have negative effects on my grade and future career.”

Another wrote that he chose not to report “because I am a straight white male, and I would not have been taken seriously.”

Some said they did not feel the unwanted sexual activity was serious enough to report, some did not want the assailant to get in trouble, and others were not sure who assaulted or harassed them. Some respondents who reported unwanted sexual contact also reported feeling as though the University of Mississippi did not take enough action on their behalf. Several respondents wrote that the Title IX office did not produce satisfactory results in assisting with instances of sexual assault or abuse.

One respondent described their situation: “A colleague told me to keep quiet about it, But I told my chair about it anyway, and he (characteristically) looked nervous about what had happened in ‘his’ department but did not report it to Title IX. I reported it to Title IX, and they ‘forgot’ to follow up because they were ‘busy.’ My last resort (on the advice I got from HR) was to talk to University Counsel. That was almost 6 months ago. They promised to get back to me but did not.”

Thirty-three percent of unwanted sexual contact incidents occurred on the University of Mississippi campus. The remaining 69% of these incidents took place at a variety of apartment complexes, bars and other locations in the area.

LGBTQ Respondents: ‘It can be pretty rough’

“It can be pretty rough,” UM graduate student and Pensacola, Fla., native Cam Calisch told the Mississippi Free Press about navigating the social climate there. Like ASB President Mannery, Calisch was “not surprised” by reports that LGBTQ respondents reported high levels of discomfort with the social climate at the University of Mississippi.

Calisch is known in the UM community in part for organizing a protest against the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning’s installation of Glenn Boyce as 18th chancellor of the university. During the reveal of Boyce’s appointment last year, university police picked up and hauled Calisch out of The Inn at Ole Miss, then announcing that the event was canceled. The organizer told the Mississippi Free Press they left the Magnolia state due to harassment and concerns for their safety following those protests.

“I was afraid I was going to die every night because of the level of harassment and threats,” Calisch said.

Surveys categorized by sexual identity displayed that 21% of queer-spectrum respondents were uncomfortable with the social climate on campus, with 3% responding that they were very uncomfortable. Similarly, 20% of bisexual respondents reported being uncomfortable and 2% very uncomfortable with the climate on the UM campus.

Only 9% of heterosexual respondents reported being uncomfortable with the overall climate on campus, with 2% reporting that they felt very uncomfortable.

Trans-spectrum respondents reported a much different level of comfort with the overall climate at the north Mississippi college. Thirty percent of trans-spectrum respondents reported feeling uncomfortable with the overall climate of the UM campus. Ten percent of these respondents reported being very uncomfortable with the overall climate.

Accessibility: A Campus Problem

The Americans With Disabilities Act has been enforced for almost 30 years. It provides, among other things, reasonable access to public spaces including buildings at public universities.

Of the 743 participants in the UM climate survey who reported having a disability, 14% of them indicated that they had personally experienced a barrier to access to classroom buildings. Twelve percent of respondents with disabilities reported difficulty accessing classrooms and computer labs. Others cited experiencing barriers due to insufficient parking and the variety of construction projects on the campus.

Several respondents noted that UM has a lack of general accommodations for those with disabilities. “The disability office is difficult to access, parking is a nightmare everywhere so I cannot go to a lot of places if I will have to walk too far from where I parked,” one person wrote. “I have never been to a game or the grove because it is not easy to access if you have disabilities.”

Another respondent wrote that “[c]losed captioning is not consistent across campus locations.”

Other respondents asserted that UM has failed to accommodate a broad spectrum of disabilities, including individuals who have mental or psychological disabilities.

“As someone with a processing disorder, an attention deficiency disorder, and socioeconomically restricted, UM’s charging for printing makes it difficult for me to be successful,” one wrote. “I cannot always use electronic copies to fully understand or retain information. Printed, physical copies are more accessible and charging so much for printing continues to put me in a financially restricted position.”

“UM needs to significantly reevaluate the way they approach psychological disabilities,” another respondent insisted. “UM gives lip service to being inclusive yet the reality is that student’s with psychological disabilities are disregarded and overlooked as if they’re disabilities are not real or in need of accommodation. Mental health importance is given lip service and public attention for 1 week in the law school but is lost in its day to day functioning and application to real students with real mental health issues.”

Transgender, genderqueer and gender nonbinary respondents also noted experiencing barriers on the UM campus. Forty percent of these respondents met barriers while using restrooms on campus.

“I regularly feel distressed or scared to use restrooms and other gendered facilities on campus,” one respondent wrote. “I have been followed into restrooms and harassed by people (albeit well-meaning) who have misgendered me and think I don’t belong there.”

“This campus sorely needs more gender-neutral restrooms,” another person wrote.

Cronyism and Nepotism: ‘A Practice at UM For Years’

The UM climate survey revealed high levels of dissatisfaction among both educators and employees of UM. One of the more startling statistics included in the report revealed that 60% of faculty respondents and 55% of staff members had seriously considered leaving the University of Mississippi within the past year. Fifty-eight percent of these respondents thought about moving on due to low pay, while 31% of faculty and 21.5% of staff considered leaving due to an unwelcoming campus climate.

ASB President Mannery said he had personally witnessed the departure of several staff members. “I think it was a lack of upward mobility or an opportunity to be at university where it’s a little bit more safe—in terms of comfort,” he said in the interview.

The response section of the report details a variety of reasons people had considered leaving the University of Mississippi. “I was sexually assaulted in my workplace,” one respondent said, while another named the “corrupt hiring process of the chancellor” as motivation.

These criticisms were not limited to the controversial installation of Chancellor Glenn Boyce on Oct. 7, 2019, which was prevalent in the comments. Respondents were very clear about their observations of cronyism and nepotism at UM across university departments, most of which were redacted in the report.

The athletics department was called out, however. “Athletics has been a major violator as children and spouses were given jobs in subordinate positions that ultimately reported to their parents or spouse,” one respondent stated.

“It’s so rampant,” Cam Calisch said of cronyism and nepotism on campus. Calisch, who wrote an essay for The Appeal calling for defunding the police department at UM, argues that the Boyce’s controversial appointment is simply a more blatant example of the types of professional misconduct that occurs at the university—including in the same department where this publication’s UM email series was centered.

“The journalism school—it’s just a good ole boys club. I feel like that’s where it’s the most visible, department wise,” Calisch said.

Since the UM email series ran on this news site, Interim Dean Debora Wenger sent the Mississippi Free Press a statement indicating that the journalism school was launching “anti-racist” training and a new approach to fundraising, which presumably will no longer allow journalism leaders, such as recently retired Dean Will Norton, to solicit from potential donors sending racist and homophobic emails as the MFP series revealed. Wenger has declined repeatedly to grant interviews to discuss solutions she is embracing since the public revelations, as have university administrators and journalism professors. Norton is still on salary as a professor.

Climate-survey respondents echoed Calisch’s concerns about hiring, alleged retaliation against whistleblowers and playing favorites around the university, not just in the journalism school.

One wrote: “A director recommended his son-in-law for a management position that reported directly to him. When one person on the hiring committee pointed out that someone might feel uncomfortable/fear retaliation when coming to him with a complaint against his son-in-law, the director became enraged. The whole department was retaliated against. (No raises, given new job descriptions, refused to replace broken equipment.)”

Another respondent reported a similar incident. “I was a member of a search committee,” the respondent wrote. “And I was told by senior faculty that a certain candidate would be hired who was not the committee’s majority choice and who had been deemed ‘unsatisfactory’. The candidate was a long-time friend of the two most senior faculty members and there was an unspoken threat to the two junior committee members.”

Politics in Higher Education

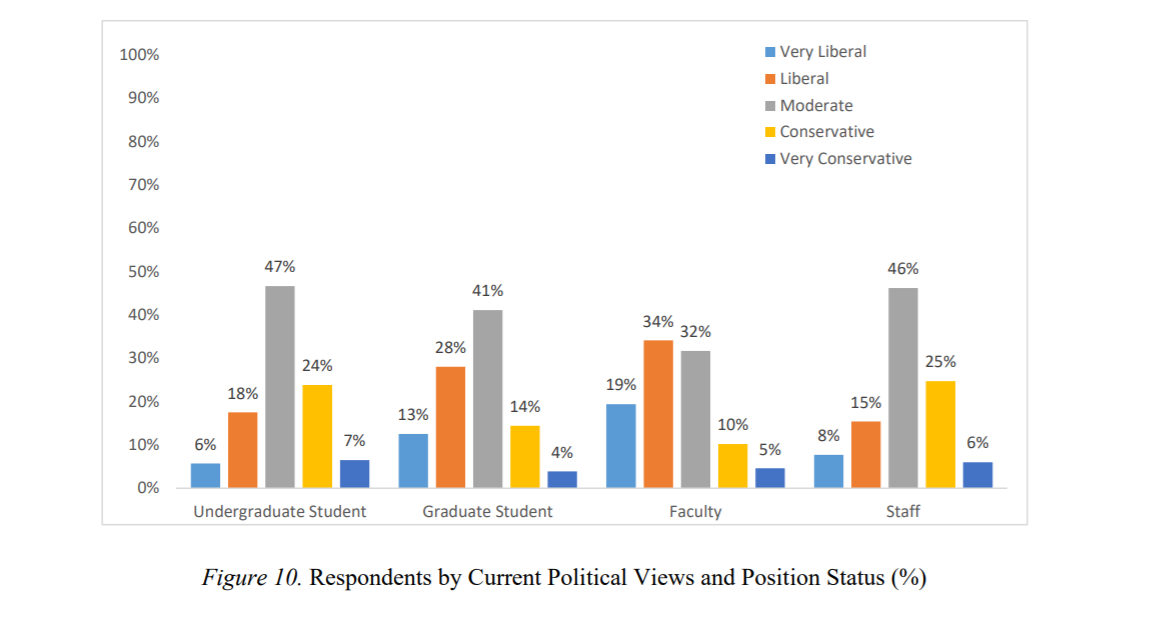

The final report by Rankin & Associates displays broad political representation at UM.

Although the political identities at UM vary greatly, those with true power and influence over the university’s response to crises belong to a smaller, less diverse group.

“When it’s time for a crisis to be managed, only a select few people actually manage it, and a lot of what goes into the decisions remains behind closed doors,” ASB President Mannery told the Mississippi Free Press in October. This publication has found that the public-university employees working toward solutions are not allowed to speak to the public about their efforts at positive change.

The Chronicle of Higher Education reported in late September that university boards in the United States often operate along partisan lines: “In recent years, a number of politically appointed public-university boards have used their broad powers to wade into contentious territory that often splits along partisan lines—setting policies around free speech, scrutinizing the perceived ideological underpinnings of curricula, targeting protections of tenure, and restraining collective-bargaining rights.”

Although political perversion of American educational institutions is cause for concern, these efforts have long been a part of the historical record. In an article for the New York Review of Books, Ruth Ben-Ghiat describes historical efforts to squash liberal minds and pedagogy. “The Italian fascist regime provided the template for right-wing authoritarian actions against faculty, staff, and students deemed political enemies,” she wrote.

“Leftists, liberals, and anyone who spoke out against the government were sent to prison or forced into exile. Since most universities were public, funds could easily be redirected; and because professors and researchers had civil servant status, they could be pressured through bureaucratic means.”

Administrators at UM have certainly ventured into what The Chronicle of Higher Education called “contentious territory.”

A more recent controversy saw Mississippi State Auditor Shad White target tenured UM sociology professor James Thomas for participating in a “scholar strike” designed to educate students on racism issues to date drawing no academic-freedom defenses from the university. Plus, just days before White launched his investigation and sent agents to Thomas’ home, university officials in the chancellor’s office went after Thomas on social media for criticizing the City of Oxford’s COVID-19 safety decisions.

The Mississippi Center for Justice is defending Thomas—headed up by famed Jackson attorney Rob McDuff, who represented Curtis Flowers, a man who spent nearly 23 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. McDuff said that the statute White claims Thomas violated does not apply to the professor. UM has not released an official response on the matter, nor has it defended Thomas’ right to free speech, only stating that university officials are unable to offer comment on personnel matters.

Several respondents in the campus climate survey stressed that Chancellor Glenn Boyce’s appointment was inappropriate. Boyce’s placement bypassed a process that would have considered other candidates. His former position as IHL commissioner was seen as having a direct influence on the Board of Trustees, the governing body of the IHL, which appointed him.

Previously, Boyce had served as the president of Holmes Community College and before that had held leadership positions in three different segregation academies in the state, the Daily Mississippian reported. Boyce also served as headmaster of Hillcrest School in Jackson, which grew out of the racist Council McCluer, established by the Citizens Council as a response to forced school integration in early 1970, the Mississippi Free Press later found.

Gov. Phil Bryant, whose term ended in January 2020 (and who graduated from Council McCluer High School) was the first governor in Mississippi’s history to appoint all 12 members of the IHL board.

Claims of hostile conduct due to disagreements in political ideology cited in the climate-survey responses underscore the severity of political division at UM. The climate report sorted students, faculty and staff by political views. Of the 916 respondents who reported exclusionary, intimidating, offensive and/or hostile conduct while at UM, 22% reported that it was due to their political views.

Undergraduate respondents mostly self-identified as moderate, at 41%, with 31% favoring conservatism, and 24% favored liberalism.

The majority of graduate students declared being either liberal or moderate, 41% each, with only 18% identifying as conservative. Fifty-two percent of faculty identified themselves as being liberal, 32% stated they were moderates, and 15% identified as being conservative.

Staff numbers favored moderate political views, with 46% identifying as such. Twenty-three percent claimed that they were liberal, while 31% identified as conservatives.

What Are the ‘Next Steps’?

The burden of change may weigh heaviest on the young leaders who choose to invest their time and money in the University of Mississippi, but those on the ground are nothing if not determined. Joshua Mannery spoke of being uplifted in spite of UM’s maladjusted campus climate. Seeing his peers and mentors succeed reminded Mannery exactly why it is worth it to fight.

“You remember the importance of being committed to the university and pushing through,” he said in October.

Likewise, officers of the recently formed University of Mississippi Black Caucus told the Mississippi Free Press in August that UM administration had to embrace transparency and be more proactive about problems marginalized students and faculty face there.

“My point is,” UMBC Historian and Stamps Scholar Tyler Yarbrough of Clarksdale says, “I think the university needs to yield to its history. Stop and look directly in its face.”

UMBC Vice President DeArrius Rhymes of Hazlehurst said about the university putting donor desires above the involvement and concerns of Black students. “They need to start being proactive instead of just active.”

The final Rankin & Associates report declares the UM climate survey itself evidence of university leaders committing to providing an inclusive and respectful campus for all, adding the caveat, “Assessments and reports, however, are not enough to effect change.”

The final report also lists the next steps in UM’s search for data that would help them effect change at the campus: “Following the fall 2020 results presentation, the executive summary, full report and recording of the presentation will be available to the campus community. A feedback form will also be available at yourvoice.olemiss.edu to allow faculty, staff, and current students to offer recommended actions and priorities.”

Additionally, the report states, “Five campus forums will be held to discuss the development of action items which will then be shared with the university community.”

As with earlier Mississippi Free Press reporting on UM emails and the Confederate statue/cemetery controversy, University of Mississippi officials declined to allow interviews with administration or other UM public employees associated with this survey about its findings and planned solutions. Associate Director of Strategic Communications Rod Guajardo Garcia contacted this reporter following an email interview request to UM employees responsible for conducting the survey. Guajardo told the Mississippi Free Press that questions about the climate report would only be addressed via email with a list of questions provided in advance—a practice that violates our journalistic standards policy.

Those tight controls of information flow illustrate Cam Calisch’s view of what is holding the public university back from true transparency and effective solutions. “Generally,” Calisch said, “a lot of these problems would be better if there were just more democratic channels for people to have a say in what the environment looked like.”

________________

Recommended: Read full UM Emails reporting series to date:

Also see: From Racist Emails to ‘Witch Hunts’: A UM Emails Timeline

Watch: Reporter Ashton Pittman and Editor Donna Ladd discuss the UM email series during the 2021 Ancil Payne Award for Ethics in Journalism ceremony (40:00) and read more about the award here.

Read the full UM Emails reporting series to date:

- ‘The Fabric Is Torn In Oxford’: UM Officials Decried Racism Publicly, Coddled It Privately

- ‘The Ole Miss We Know’: Wealthy Alums Fight To Keep UM’s Past Alive

- UM’s ‘Culture Of Secrecy’: Dean Quit As Emails Disparaging To Gay Alum, Black Students Emerged

- ‘Appalling’: UM Provost Decries ‘Hurtful’ Emails About Black Women, Gay Alum

- Ole Miss’ Coddle Culture: Ole Miss Will Stay ‘Ole Miss’ Without Radical Shift

- EDITOR’S NOTE: The Decisions, Process, Motives Behind Ashton Pittman’s Series On UM Emails

- Perpetuating Patterns: It’s Time To Build A Better University Of Mississippi

- After UM Emails, Dean Plans ‘Anti-Racist’ Training, Donor Changes to ‘Remake Our School’

- ‘Ole Miss’ Vs. ‘New Miss’: Black Students, Faculty On How To Reject Racism, Step Forward Together

- UM Closely Guards Climate Survey Providing Window Into Social Issues, Sexual Violence

- UM Probes Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails As Ex-Dean Keeps $18,000 Monthly Salary

- ‘Our Last Refuge’: UM Faculty ‘Terrified’ As Officials Target Ombuds In Bid To Unmask Whistleblowers

- ‘Like He Was Disappeared’: UM Faculty Fear Retaliation After Ombudsman Put On Leave

- UM Appoints Acting Ombuds As Weary Faculty See Effort To ‘Stamp Out’ Anti-Racism Voices

- UM Retaliating Against Ombudsman for Protecting Visitors’ Privacy, Org Says

- UM Accuses Ombudsman of ‘Raising False Alarms’ Over Whistleblower Investigation

- A Matter Of Trust: UM Controversy Shows How Ombuds Programs Should, Shouldn’t Function, Expert Argues

- UM Pursuing ‘Criminal Investigation’ Into Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails

- Ombuds ‘Exonerated’ As UM Emails Whistleblower Hunt Fails to Identify Sources

- Will Norton, Ex-Dean in ‘UM Emails’ Race Saga, Quietly Departs University