When French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr stated, “the more things change, the more they remain the same,” he was not specifically thinking about voter suppression, but he sure could have been. Voter suppression has plagued our nation’s electoral process for as long as African Americans have been free from bondage, and the fiasco we witnessed on television recently in Georgia serves as a reminder that voter suppression is alive and well in 2020.

As executive director of a nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting voter suppression, I am frequently asked what “voter suppression” means. Demand the Vote, a nonpartisan group that provides voters with registration and election information defines “voter suppression” as “any effort, either legal or illegal, by way of laws, administrative rules, and/or tactics that prevents eligible voters from registering to vote or voting.”

While voter suppression disproportionately affects African American voters, it also has a negative impact on women, college students, disabled, low-income and homeless populations.

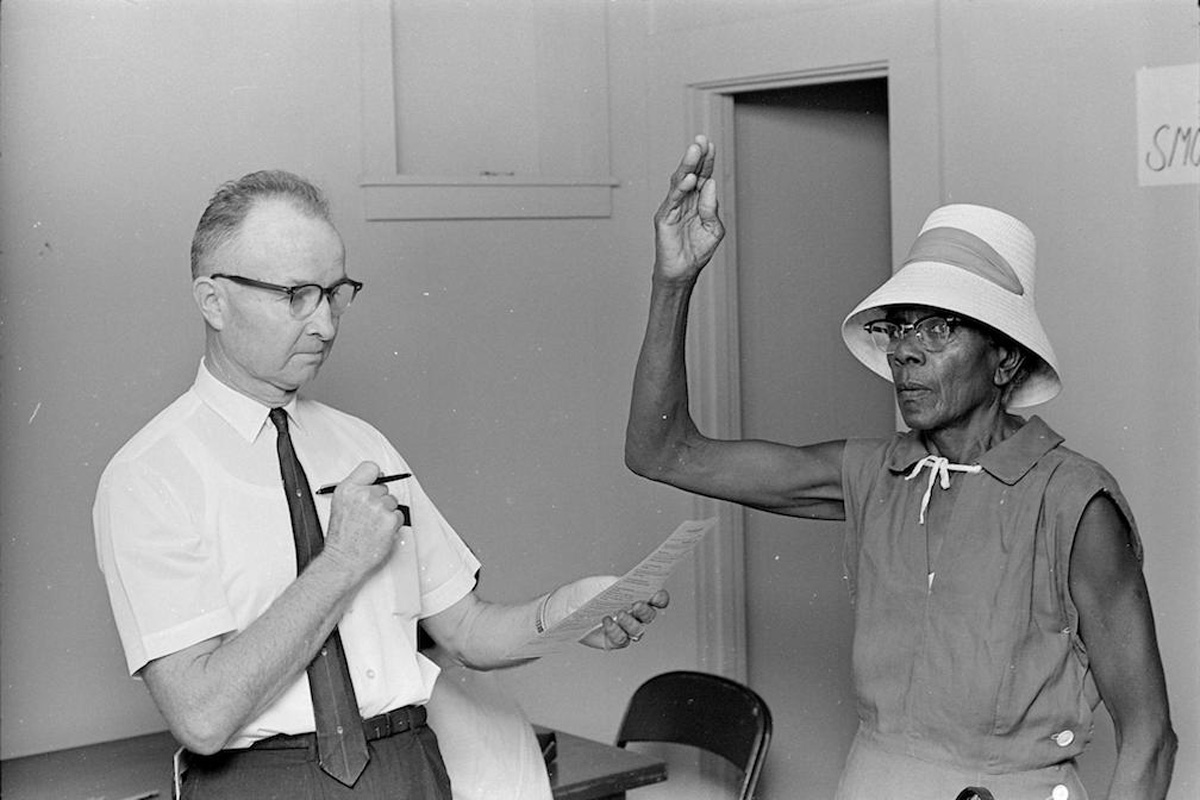

The Civil Rights Movement and Voting Rights Act ended voter suppression in the forms of lynchings, bombings, cross burnings, “bubbles in a bar of soap” tests, literacy tests and “good character” tests, but other forms of suppression survived the federal laws and continue to thrive.

The gerrymandering of legislative districts consolidates Black voters into supermajority minority districts, thus reducing the overall number of competitive districts in which African Americans influence the outcomes of elections. Segregation-era laws banning felons and ex-felons from voting survived the Voting Rights Act and continues to disproportionately disenfranchise African American men.

Modern voter-suppression tactics took on new forms toward the end of the Jim Crow era with the advent of voter ID laws, which disproportionately affect minority populations, particularly older African Americans who may not possess birth certificates. In 1950, South Carolina passed the nation’s first voter-identifications law. The South Carolina law did not require a photo ID, but it did request voters to present a document bearing their name at the polls. The trend continued with Hawaii (1970), Texas (1971), Florida (1977) and Alaska (1980) passing their own versions of voter ID laws, and by 2000, the number of states with voter-identification laws quietly reached 14. Both Republican- and Democratic-controlled legislatures passed these laws.

States Collectively Closed Over 1,000 Polling Places

The bipartisan Commission on Federal Election Reform’s 2005 recommendation for voter ID at the polls brought the debate to the forefront of state politics across the nation. This new era of voter ID laws ushered in the stricter form that we are more familiar with today.

In 2008, with the decision in Crawford v. Marion County, the U.S. Supreme Court approved Indiana’s law requiring voters to present an ID at the polls in order to vote a regular ballot. After the Crawford ruling, Georgia joined Indiana in becoming the first states to require an ID to vote a regular ballot. Voters in those states lacking such IDs could only vote provisional ballots. Provisional ballots are counted only after the voter returns within several days with the required ID. From 2011 through 2013, many more states passed their own versions of voter ID laws and today the total number of states with voter ID laws on their books stands at 36.

Voter suppression did not stop there.

Prior to the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Holder v. Shelby, the Voting Rights Act required federal pre-clearance of changes to voting laws and practices in states with historically discriminatory voting procedures, Mississippi included. In the 5-4 decision of Holder, the Court found that the two pre-clearance sections of the Voting Rights Act were unconstitutional. The Court’s removal of pre-clearance from the Voting Rights Act gave states carte blanche to enact new methods of voter suppression. States wasted little time.

After the Holder decision, states collectively closed over 1,000 polling places with a disproportionate number of the closings in predominantly African American communities. Polling-place closures cause Election Day confusion, longer lines and lengthier waits at newly consolidated polling places. Placing an inadequate number of voting machines and malfunctioning voting machines in strategically targeted polling places also creates long lines and long waits.

Many voters are limited to small windows of time for casting their votes. Some voters are mothers of young children or caretakers of elderly family members. Other voters are hourly workers who simply can’t afford to lose the hours waiting to vote. The engineered long waits result in these voters giving up on the process.

Newly Popular Voter Roll Purges

While the Holder decision resulted in other suppression tactics such as reductions in early voting and stricter voter ID laws, it is the newly popular voter roll purges that have been the most effective voter-suppression methods used. Many secretaries of state tout a postcard voter purge scheme as an efficient and necessary method of “cleaning up” voter rolls. Under the scheme, voters are mailed non-forwardable postcards to their last known addresses. If voters do not take action based on the instructions provided on the postcard, or voters have moved and the postcards are not forwarded, then the voters are purged from the active voter rolls.

A good example of how this scheme works is in Alabama, where Secretary of State John Merrill’s totals for purged voters stands at over 790,000 since 2017. As one might guess, a large number of these purged active voters are African American. Many of the purged voters personally interviewed claim they never received the postcards and were not notified afterward that they were removed from active voter rolls. These postcard purges are occurring all over the country.

COVID-19 exposed another layer of voter suppression and discrepancies between states’ alternatives to in-person Election Day voting. Many states offer voters early voting, curbside voting and vote by mail, but not Mississippi. The only real alternative to in-person voting for Mississippi voters is absentee balloting, but only a small subset of voters qualifies for this safer alternative.

Even states with strict absentee balloting similar to that of Mississippi elected to loosen their requirements to allow all voters the choice of applying for an absentee ballot because of the COVID-19 risks associated with in-person voting, but not Mississippi. For many Mississippi voters, exercising their right to vote in November is a forced choice between exposure to COVID-19 or not voting.

Solutions: Making Your Vote Count

So how do we fight back against voter suppression? Part of my job as executive director of Vote Alabama Association is to explore ways for individual voters and groups to protect voting rights in this hostile era of voter suppression in which we find ourselves this election cycle.

Here are steps you can take in Mississippi to make sure your vote counts on Election Day:

- Check your voter registration status regularly. Treat your voter status like you do your bank account so there are no Election Day surprises. Click here to check your Mississippi registration status.

- Share the voter-registration status link with family, friends and neighbors. Help those who can’t check for themselves by checking their registration status for them.

- Check your polling place several times prior to Election Day for closures and consolidations. Check the Monday before Tuesday’s election. You do not want to show up at the wrong polling place. Here is the link for checking.

- Share the polling-place link with family, friends and neighbors. Help those who can’t check for themselves by checking their polling place for them.

- Develop an Election Day plan for yourself and for any family, friends, and neighbors needing assistance to and from the polls. Make sure you have your required IDs. Plan to vote early to avoid long lines that build up throughout the day. Know what the weather will be like on Election Day. Bring folding chairs, umbrellas, water and snacks in case lines are long.

- If you qualify under Mississippi law, vote by absentee ballot. This is the safest way to vote during the pandemic. Click here for the absentee ballot request.

- If you have family members over the age of 65, help them secure an absentee ballot request so that they can safely vote this election cycle.

- Get involved with a voting-rights organization in your community or region of the state. Organizations are always looking for virtual volunteers to help fight back against voter suppression. This election cycle, virtual volunteers are making huge impacts without even leaving the safety of their own homes.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.