Summer was in full swing as I drove up Highway 16 in June 2005, window cracked to let out the cigarette smoke. Coldplay’s “X&Y” album occupied the CD player since my way-cooler best friend wasn’t in the car to advise against it. I had just graduated from the University of Mississippi with a degree in Southern Studies, and I was wearing out those two-lane southern highways, commuting to and from Philadelphia, Miss. With press credentials around my neck, I felt alive, purposeful, authentic as I drove daily to sit in the courtroom during the overdue prosecution of Edgar Ray Killen. He had helped orchestrate the 1964 civil-rights murders the State of Mississippi had never tried to prosecute.

“Natalie Irby, 23 and looking more rock ‘n’ roll than the rest of the media with tattoos peeking out from under her sleeves, stood in a circle of media, her pen poised over her notebook…”

I adore that 23-year-old that my editor wrote about later. Fiery-eyed, staunchly opinionated, heart of social justice on her sleeve, obsessed with the South’s sordid racial history, determined to be a part of the solution, and hoping to play even the tiniest of roles in righting the wrongs of the past. She had that young kind of passion. The kind that’s borderline annoying at all times. The kind that has yet to doubt the possibilities for change.

“As cameras clicked all around her, Irby stared intently at the petite, gray-haired woman in the middle of the media circle on the third day of the Edgar Ray Killen trial in June 2005…”

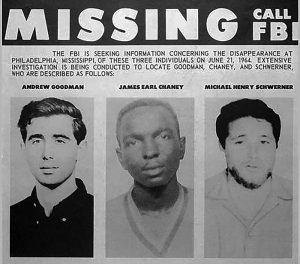

The “petite, gray-haired woman” was Rita Schwerner Bender, the widow of Michael Schwerner, his name most often written alongside James Chaney and Andrew Goodman. You know who they are. You know that they were civil-rights workers. You know that Klan members, including local law enforcement, abducted and murdered them on the first day of Freedom Summer in 1964. And you know this because the nation was spellbound, shocked, outraged and demanded action, leading to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Crimes against civil rights workers were nothing new; it’s just that too few people were paying attention. And, frankly, disappearances weren’t a new thing, either. Black men “disappeared” at the hands of southern, white perpetrators, and nothing was ever done about it—their lifeless bodies inadvertently found in a river at some point or another. But, in the case of “Mississippi Burning,” Goodman and Schwerner were white and came from well-connected white families up north.

It’s as if the nation thought to itself, “Dang. We’ve gotta do something about this. It must be really bad down there if they’ve started going after white people, too.”

“Natalie didn’t ask any questions; she just stared as Bender dressed down the press corps for not doing more to reveal, and undo the effects of, this statewide conspiracy to forcibly deny black people the same rights as white people.”

It had been 41 years since the murders of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, as Rita Schwerner Bender stood on the lawn of the Philadelphia courthouse tackling rapid-fire questioning with the same iron-clad composure, poise and presence as she had done back in 1964 in Mississippi. At no point did she fumble over a thought, word or potentially tongue-twisting phrase. Captivated by her effervescent strength (a combination I’d never before witnessed), I wondered what it was like to be her—this tiny yet mighty survivor.

This is a woman who applied to the Congress of Racial Equality to come to Mississippi with her husband to set up a freedom school for African Americans and help them register to vote in a culture of racist violence. She wrote in her application to be part of the field staff in the state: “I wish to be an active participant rather than a passive onlooker. As my husband and I are in close agreement as to our philosophy and involvement in the civil rights struggle, I wish to work near him in whatever capacity I may be most useful. My hope is to someday pass on to the children we may have a world containing more respect for the dignity and worth of all men than in that world which was willed to us.”

I was mesmerized that, even though decades had passed, she echoed the same sentiment, with the same degree of fervor as she had after her husband was killed in 1964: “You’re here, you’re interested in this trial as the most important trial in the Civil Rights Movement because two of the men were white. You’re still doing what was done in 1964.”

It’s been 15 years since I walked up to Rita Bender and shyly asked to shake her hand. That fiery-eyed 23-year-old version of me may look like a less fiery 38-year-old today, but she is still opinionated. Her approach is just different. She does a lot more listening and a lot less lecturing now.

“[T]he curtain is not pulled back for some national media corps; the curtain has been pulled back for all of us. It is just now that the reality behind that curtain is not being considered taboo by an overwhelming majority of Mississippians. That is nothing of which to be proud.”

I wrote those words in 2005 in a column about the trial. Now, the older Natalie knows that anti-racism work goes far beyond making violence of old Klansmen less taboo. It’s about changing the very core of systems that were built upon a foundation of white supremacy and confronting implicit bias head-on.

While reflecting upon that summer in Philadelphia, I started thinking about the ways in which systemic change has been accomplished and how justice has been achieved, in varying forms throughout history, and a combination of words comes loudly to the fore for me: sustained interest. People have to continue to care. If it weren’t for a group of people calling for the “Mississippi Burning” cold case to be reopened, it wouldn’t have happened. And those murders occurred 41 years ago.

Once an event is long out of the public eye, once there are no protests or breaking-news segments, that’s when the real change starts. That’s when it gets tough. The performative aspect of protesting can be empowering and exciting, the collective energy intoxicating. And that’s not a bad thing. That’s one of the motivators—a “we’re all in this together” mantra. Knowing you are part of something larger than you.

But there is nothing exciting about trying to right the systemic wrongs of society. It’s not fun. It’s arduous work. Change happens incrementally. And it’s the incremental nature of systemic change that requires a steady rhythm of persistence, perseverance and memory. It can take years, even decades. But it’s never too late.

It’s our job to make sure righting the wrongs of history, whether it be the history of yesterday or of long ago, remains a priority in the collective consciousness. It’s our responsibility to ensure that a fervent hum of justice continues to rumble inside our hearts.

June 2005 was one of the most impactful times in my life. Being a part of history, in such an active way, left an indelible mark. Rita Schwerner Bender is still my hero. And when I found myself in the middle of a field in rural Neshoba County with legendary veterans of the Civil Rights Movement (my version of celebrity) holding hands in a unity circle and singing “We Shall Overcome,” I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

These legends know better than anyone that the journey is long. And that incremental change can be frustrating, especially in a society accustomed to instant gratification.

But in the end, it’ll all be worth it.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.