This past month has been difficult for everyone, everywhere and in every way of human consciousness. The heightened emotions, feelings, passion, sentiment and reflection are the dramatic result of the horrible, heinous and horrific death of George Floyd.

Indeed, these very emotive difficult days have been and will be on our minds in these bewildering times of social injustice, bigotry, police brutality and human indecency. The celebration of Juneteenth this week means even more emotion and grief. On June 19, 1865, Major Gen. Gordon Granger and a group of Union soldiers landed at Galveston, Texas, where they shared the news that the Civil War was over and enslaved people were free. It was two and a half years after President Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863.

Juneteenth became a special day of recognition for a historic celebration that marks the landmark proclamation for the end of slavery—a very sensitive topic these days as all of us continue to struggle with our past history, present circumstances and future trajectory toward much-needed positive change.

A Hard Time Finding a Job as a Black Man

My wife and I intend to use Friday, June 19, for prayer but also to celebrate another unrecognized point of reference in American history. It has to do with the history of the cell phone—the device that captured the image of the white police officer kneeling on the neck of George Floyd and the one that captured the white female dog walker falsely accusing the bird-watching African American man of threatening her in daylight in New York City’s Central Park.

In both cases, and so many others in recent years, the cell phone has become an electronic instrument for bringing truth to life by capturing the troubling, disconcerting, disturbing and awful behavior of a white woman in one case and, in the other, the violent behavior of a white man wearing the uniform that symbolizes those who should protect human life, not end it. The cell phone has enhanced human life in so many ways and enabled us in both cases to see two tragic images.

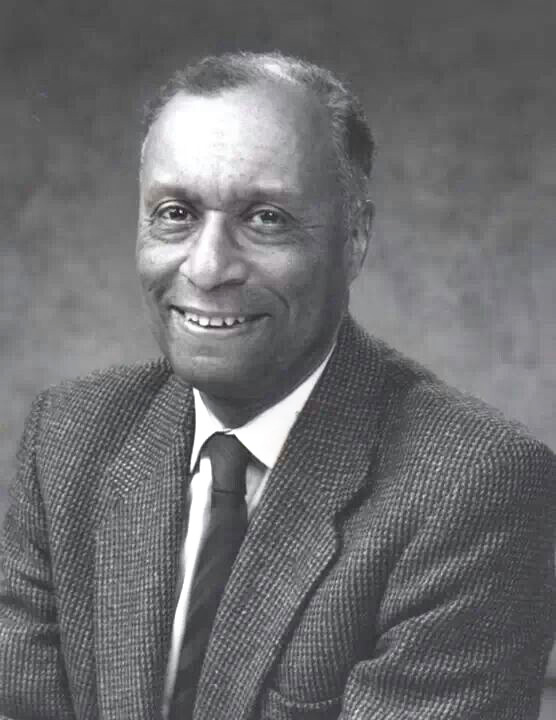

Ironically, an African American man co-created and patented the technology that led to the cell phone that now exposes so much racism and violence. I told my son when he was younger that much of life is about mystery, contradiction, hypocrisy and irony. The inventor, Dr. Henry T. Sampson Jr., was born in Jackson, Miss., in 1934 and went on to attend Morehouse College and then graduate from Purdue University in Indiana, where he had established the Omega Psi Phi fraternity chapter there.

After Sampson graduated, he had a hard time finding a job as a black man, but finally landed at the U.S. Naval Weapons Center in China Lake, Calif., where he worked as a research chemical engineer from 1956 to 1961, working on high-energy solid propellants and case-bonding materials for solid-rocket motors.

“The U.S. Naval Ordinance Test Station was a godsend. When I graduated from Purdue, I found many companies would not hire an African-American engineer,” Sampson said in an article on the Purdue website. He later earned a M.S. in chemical engineering from UCLA, and a M.S. in nuclear engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

He became the first African American to earn a PhD in nuclear engineering in the United States.

As a nuclear physicist, Sampson co-invented the “gamma-electric cell”—technology later used to create the cell phone—and received its patent along with George Miley in 1971. It ignited high-voltage output with detected radiation.

Shifting Angst to Invention and Innovation

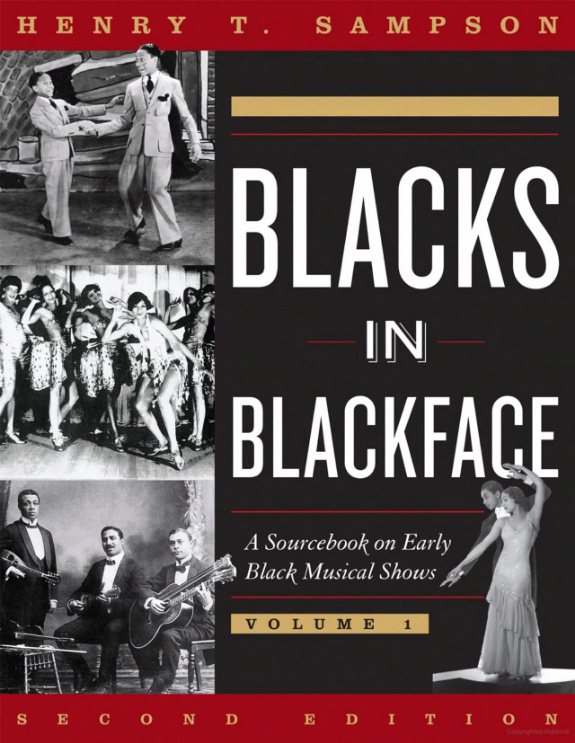

Henry Sampson, who died in 2015, was also a noted filmmaker and authority on often-ignored African American contributions to U.S. stage and cinema starting after the Civil War. He wrote seven books including a two-volume set, “Blacks in Black Face: A Source Book on Early Black Musical Shows” released in June 2014. His father H.T. Sampson Sr. was a dean at Jackson State; the library there is named after him.

Younger readers need to know stories of black Americans like the Sampsons as they personally agonize and experience anger over the death of George Floyd today. Perhaps these young minds can shift their angst to invention and innovation. One African American’s invention became an instrument of justice for another African American man’s unconscionable killing.

So, this coming Friday, we are sending up prayers to painfully celebrate the life of George Floyd, prayers for the reflective celebration of ending slavery in America, and thankful prayers to Henry Sampson for his remarkable invention of cell-phone technology. We will give thanks for the cell phone’s timely utility to face and confront social injustices and—in the most urgent way—position all of us to move forward with respect for human decency, compassion, dignity and innovation.

Yes, the same type of innovative thinking Henry Sampson did for all of us can also be used among all of us now to find bold, new innovations for equitable and equally centered human existence.

I encourage MFP readers to pick up my upcoming books about two other remarkable African American men. “Martin’s Mnemonics” and “Malcolm X’s Passport” are about two men who also tragically died in America during our earlier societal struggles with social injustice, bigotry, police brutality and human indecency.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.