Ever since the details of the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd flooded national news, we have all witnessed protests erupt around the nation.

The men and women who have taken to the streets in droves have turned militant at times with righteous anger, grief and calls for justice.

In turn, mostly white officials who benefit the most from the racist power structure, such as Madison County prosecuting attorney Pamela Hancock, have mischaracterized the actions of the masses as “riots,” and she even wished a deadly pandemic upon them. In so doing, the likes of Hancock have attempted to frame those people demanding justice, and those turning to violence in response to their oppressive conditions, as criminals who deserve to be dealt with through the same brutality that led to the protests in the first place.

We must try to recognize that the urgency in the peaceful calls for change in America we see in so many protesters is rooted in the same impulses that have led some to destroy property and physically attack what they see as the symbols of white supremacy and power in their communities.

When people are locked in the grips of poverty and racism, when their voices are drowned out and ignored, and when their hopes are dashed, they turn to the only forms of protest they have at their disposal. As we have seen in the past weeks, Black communities have predictably, virulently and understandably exploded.

The misuse of the term “riot”to describe the visceral reactions of marginalized communities to oppression has historically been a tool in the hands of white supremacists and the powerful in America. They have used the word to ruthlessly dispel legitimate concerns over poverty and racism, to dismiss protesters as criminals and to blame the oppressed rather than adequately deal with the systemic causes of the protests in the first place.

Such a narrative is familiar to those who lived through and remember the Gibbs-Green tragedy in 1970 at Jackson State University.

Physical and Psychological Scars of Police Violence

Just a few short weeks ago, JSU held a virtual 50th commemoration to mark the police shootings on campus that left two young men dead, Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Green. More than a dozen people were shot in the wanton attack on Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, and scores of others bear the physical and psychological scars from that night.

In large part due to the rhetoric that arose to shift the blame from the Jackson Police Department and the Mississippi Highway Patrol to the victims, most Americans and even most Mississippians do not remember what took place at Jackson State on the evening of May 14, 1970. For the better part of the past 50 years, the few people who have commented on those events have most often referred to the “Jackson State riot” in a way that is grossly uninformed and harmful.

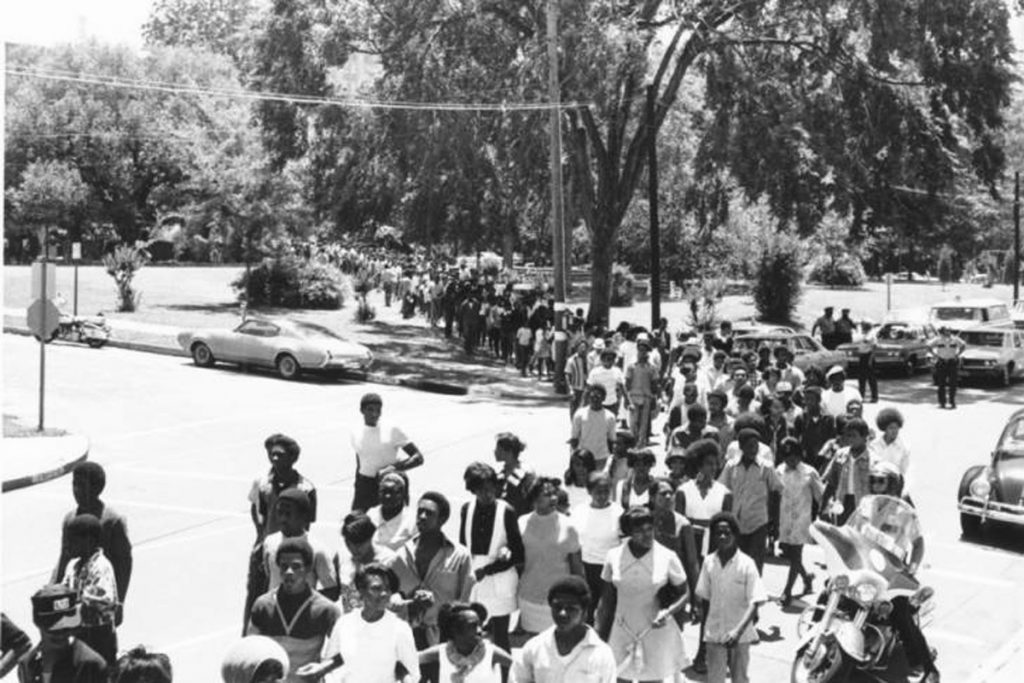

Yes, in the days leading up to the 1970 police shootings, Black protesters lined John R. Lynch Street in Jackson, and they identified more with the burgeoning Black Power movement than the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement. They armed themselves with stones and bricks to throw back at whites who attacked them, and on the night of the police murders, an unknown person blocked Lynch Street with a dump truck and set it on fire in order to bring the traffic to a standstill.

In response, the white-supremacist regime launched a murderous assault in the dead of night when no one was protesting at all. They erroneously claimed that a sniper had been firing on them from Alexander Hall, and the narrative of a “riot” further fueled notions that somehow the young people, who faced the horrors of that night and continue to live with physical and psychological trauma, deserved to be punished.

By the mid-1960s, African Americans and activists realized that groundbreaking achievements such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act did not remove the systemic barriers to achieving basic human dignity that had been erected over two centuries. Those laws did nothing to erase the physical threat of white supremacy.

From Detroit to the the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, similar scenes of urban uprisings played out across the country, including the nationwide unrest after the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis.

protesters by Mississippi law enforcement officers at Jackson State College. The shootings wounded 12 students and killed Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green. Photo: Kudzu, David Doggett (Jackson).

‘The Will, the Stamina, the Ethical and Moral Imperative’

While on the faculty at Jackson State, the scholar and writer Margaret Walker remarked on the violent aftermath of Dr. King’s death. More than a week and half after he was killed, she returned to her childhood home of New Orleans to find it “still having fires from the disturbances that followed the death of Dr. King.”

“I tremble to think that the Negro people may resort more and more to violence, while the nation at large tends to stiffen its hostility to all Negroes,” Walker said then. “The American people must set this house in order, but doing so is a herculean task…. Can and will America solve her problems of the ghettos in the inner city? Does she have the will, the stamina, the ethical and moral imperative?”

Rather than seeing protests of the late 1960s as calls for revolutionary change, just as this nation had been founded in armed revolution, white Americans branded those bloody days as “riots” and put them down with ferocity, just as they did with the Gibbs-Green tragedy at Jackson State. Instead of summoning “the will, the stamina, the ethical and moral imperative” to address the underlying issues of racist oppression, white leaders doubled down on their hegemony.

As we watch the news today of people in the streets lashing out in frustration and many demanding justice for Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd with strident militancy, we should remember that what we are seeing is intrinsically linked to our history.

We would do well to heed the calls for fundamental change, stand with the protesters, understand the looters, reform how our communities are policed, demand that our leaders value the dignity of all people and finally assure that Black Lives Matter.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.