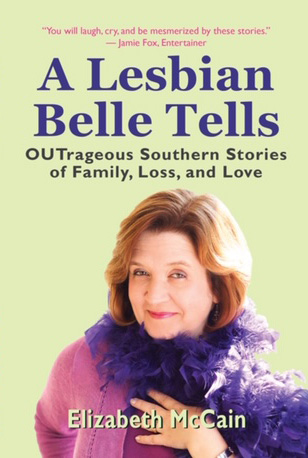

A purple boa curls into a feathery collar on the cover of Elizabeth McCain’s new book—a whimsical nod to her knowing half-smile, her extrovert nature and a pivotal moment that preceded her life as a lesbian.

The boa shows up early in her just-published memoir, “A Lesbian Belle Tells: OUTrageous Southern Stories of Family, Loss, and Love,” as a prop in a ploy that goes maddeningly sideways. The Mississippi native, who has called the Washington, D.C., area home for most of her adult life, was dating a man there in 1991. One night, she went to his apartment to try to seduce him, wearing her purple boa.

McCain thought they were deep into a romantic scene when he suddenly asked, “Elizabeth, have you ever thought about becoming a lesbian?” She hadn’t.

“What the hell, David?”

She asked why he thought such a thing, then ticked off the stereotypes she didn’t fit. David noted her love of going to women’s Goddess circles and said she seemed to come alive more around women than with him. He offered to introduce her to some cool feminist lesbians from grad school.

“Of course, I was outraged,” she says by phone after recounting the scene to the Mississippi Free Press.

But later, pondering his question, McCain was admittedly a bit intrigued. She took it to her therapist. Was he picking up on something in her subconscious?

“I began my journey of exploring my sexuality, and thank goodness I was in Washington, D.C., instead of Mississippi in 1994,” she says. “That would have been a little more difficult, I believe.”

‘The Vulnerability and the Power’

The memoir follows McCains journey of identity, relationships, estrangement, expectations and spirituality. Through sharing her own navigation of coming out, community, connection and forgiveness, she hopes to help others reframe and reclaim their stories, and heal.

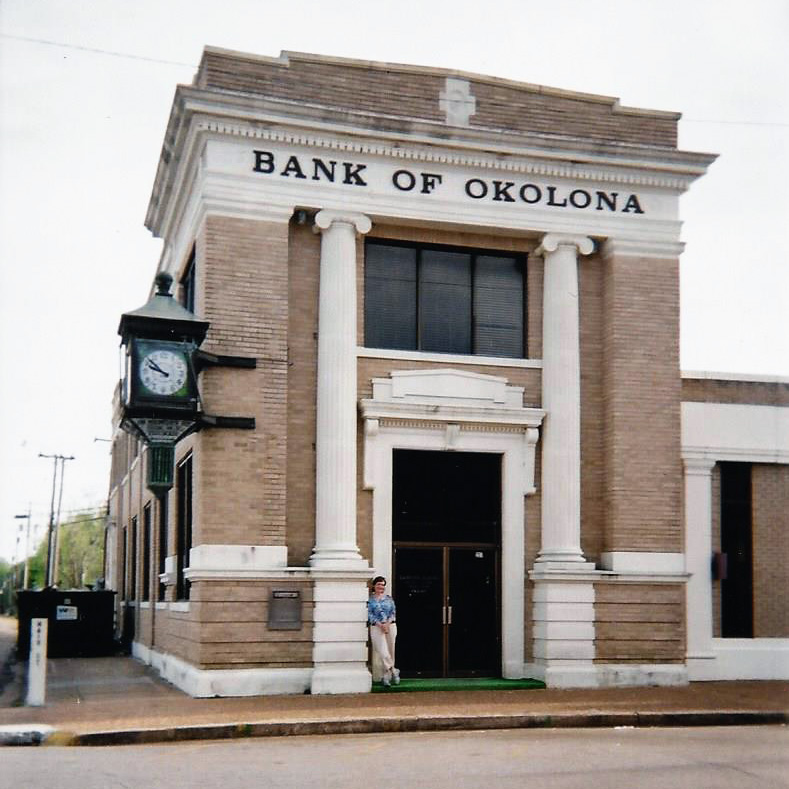

McCain, 56, lives in the Maryland suburbs near Washington, D.C., with her spouse, Marie. She grew up in the small northeast Mississippi town of Okolona, the youngest of four children (with a nine-year gap to the next-oldest). Her dad was president of the bank her grandfather started; her mom hewed close to conservative Christian teachings.

“As a Mississippian, of course, my childhood was steeped in stories,” says McCain, recalling the wild tales her father would tell as they rode in his pickup to look over his soybean fields. “And … growing up in a small town, as you know, everything’s a story.” Lively porch parties at her mother’s and aunts’ summer house in Monteagle, Tenn.—a retreat they called Southern Comfort—continued the storytelling tradition.

So, that pump was primed long before McCain—interfaith minister, spiritual counselor and energy therapist with a 20-year career as a psychotherapist—discovered storytelling as an art form. That was in a workshop more than a decade ago. She’s subsequently added transformational storyteller and story coach to her professional profile.

“I love the vulnerability and the power of personal stories … that touch people’s hearts,” she says.

‘Girl, You Gotta Write A Book’

McCain first gathered her own stories in her one-woman play, “A Lesbian Belle Tells …,” that won a best solo show in the 2014 Capital Fringe Theater Festival in Washington. Friendly teasing by D.C.-area pals prompted the title term. “I’m still obviously very southern. I never lost that identity, and that’s always been really important to me,” she says. She was a southern belle, her friends would say, but a lesbian southern belle.

“It’s kind of two polarities, in a way—growing up in a very proper, established southern family, with the expectations that I’d marry a husband, have children and be in the Junior League, and as I came out as a lesbian, that was a whole other world,” McCain says.

“Lesbian belle” integrates two key identities—as a southerner and a lesbian, while still appreciating her traditional feminine side.

“Girl, you gotta write a book,” an older woman told McCain after a Rehoboth Beach, Del., performance of her play. Those words echoed and endorsed McCain’s long-expressed desire to corral those porch stories, southern gothic tales, pains, laughs and triumphs onto the page. The personal stories were universal, with the potential to impact many, even beyond the lesbian community.

‘There’s Always Hope for the Next Generation’

Family estrangement weaves a painful thread in McCain’s memoir. Her mother, usually mild-mannered, flipped out and raged when McCain told them she was a lesbian, and her father shunned her. But, other scenes—from the way her coming-out news lands with some, to a few surprises along her trek—balance that with laughs and love. Vibrant characters such as her Aunt Liber Prichard, her mom’s sorority sister Shirley Allen and more resonate. She found acceptance with extended family, and is close to a lot of her cousins.

“There’s always hope for the next generation,” she says.

McCain hopes her memoir will inspire others to share their stories, she says, “both their painful stories and their most meaningful stories. … When we share our stories, whether on a porch, at a party or the Piggly Wiggly, there’s a spark that ignites with us, especially southerners because most of us grew up steeped in stories.

“I think sharing stories is a really spiritual experience. It’s how we connect from the heart level and the soul, and it’s the way we heal together in community.”

‘We Can Always Reframe Our Stories’

McCain never reconciled with her dad. News of his death and her mother’s subsequent stroke are particularly gut-wrenching in the book, in the heartbreaking context of family estrangement that piles on the pain. But McCain’s openness to alternative spiritual paths—“high woo-woo” as she tells a psychic at one point—brings messages of hope.

Even in the most painful stories, in the grief and loss, there are gifts. “We can always reframe our stories,” she says. “If there is a lot of loss and disconnection, how can I choose a family of choice? How can I forgive? How can I reframe my stories so I am the heroine or hero, instead of being the victim?

“It’s always really important, I think, to ascend from the underworld of grief and loss and pain, and look at how much you’ve grown from the experience,” she adds. “ … I really want to help people do that, especially the LGBTQ community.” She hopes the memoir both inspires LGBTQ people and educates straight people, reaching across differences to connect and unite.

McCain has always kept a connection with Mississippi, she says, and spent more time in her home state in recent years as she wrote her memoir, reconnecting with threads of the past. She’d stayed away from Mississippi for a long time, because of family estrangement and pain, and also its red-state politics, which are not her own.

But, she says now, “As I’ve gotten older and let go of the painful stories and kind of forgiven the past, I’ve found this renewed love for it.”

Its literary legacy (word is, her grandmother taught Eudora Welty at Central High in Jackson), its blues music and lush landscapes fascinate and inspire McCain. Negative stereotypes are still a struggle. She calls Mississippi’s HB 1523, also called the Religious Liberty Accommodations Act and widely criticized as anti-LGBT legislation, “absolutely horrid.” There’s room for growth on issues of homophobia and racism in the conservative state. And yet, Mississippians are warm and welcoming.

“There are gifts and challenges in any part of the country, gifts and challenges with any relationship. It’s all about personal connections and the way we choose to tell the story.”

McCain plans to reschedule pandemic-postponed performances of her one-woman play in Oxford and Tupelo, with hopes for a southern tour next spring with shows and book signings. She notes Jackson and the Gulf Coast as potential sites.