Brandon Presley could win his upcoming race for Mississippi governor by turning out Democratic voters who have not pulled the lever or marked their ballots in years, as well as those who may have never voted. Many of these would-be voters say the government has let them down and that the state is stuck with the party in charge, so why bother.

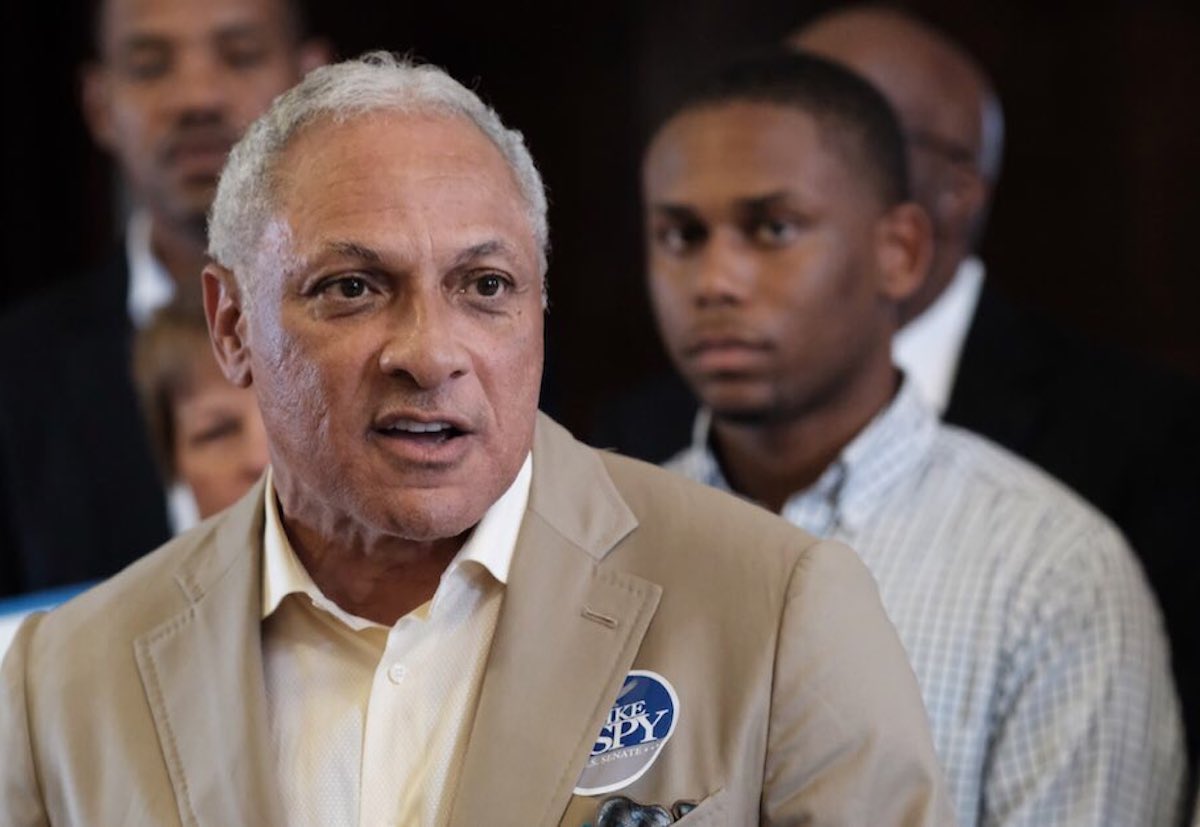

Turning out more voters to win an election sounds obvious, does it not? Nevertheless, Democratic candidates in past elections have done very little to increase turnout in many predominantly low-turnout, high-poverty, Black-dominated precincts where most “retired” Democratic voters live. Former Attorney General Jim Hood and former U.S. Congressman and Agriculture Secretary Mike Espy lost their statewide elections for governor and U.S. senator, respectively, in part because they did not pay enough attention to these enclaves of voters.

Knock on Doors, Turn Out Voters

Instead of relying only on high-tech voter-ID apps, robo calls, advertising and social-media strategies, as most candidates do these days, Presley must re-fashion the old-fashioned way of turning out votes in poverty-laden, voting precincts containing people of color. This was the approach of Mississippi Civil Rights Movement leaders in the 1960s and 1970s to register Black voters. Espy used similar tactics in 1986 to become the first Black congressman from Mississippi since Reconstruction.

Remember door-knocking? Door-knocking used to be about having conversations with mostly people of color in Democratic neighborhoods on their doorsteps or in their homes, whether they were registered or not, and explaining why they benefit by voting for a Democratic candidate.

BlueLabs, a data-service firm in Washington, D.C., and New York City that Espy commissioned in 2021, analyzed Mississippian votes in 2016, 2018 and 2020. The study found that while African American turnout had increased, white turnout was proportionally higher. White Republican voters’ tortured allegiance to Donald Trump drove them to the polls.

Progressive-leaning Black voters’ rightful loathing of Trump drove them, too. I saw that up close, working for Espy in his 2020 Senate race in Greenville, Miss., the heart of the Mississippi Delta, where I door-knocked.

Espy’s campaign staff, several decades younger than I am, argued that the GOTV, door-knocking blasts from the past stole too much time and money from faster, more efficient campaign tactics. In 2010, Democrats unleashed the VAN system, a privately owned voter database and web-hosting provider, which many Democratic campaigns now use. With the merger of NGP Software and the Voting Activation Network, VAN surpassed Republican Karl Rove’s 22-year-old microtargeting system, which helped and still helps the GOP win elections today.

VAN is known for identifying Democratic voters by what cars they drive or magazines they read and stuff like that, discovered on personal databases. VAN has worked—no doubt. Campaigners have given it rave reviews. Democrats at all levels of government are winning more races with VAN’s microtargeting tools than ever before. Importantly, the 2018 and 2022 midterm elections brought more younger voters to the polls than in the past 30 years, thanks in part to VAN’s microtargeting.

The Old-Fashioned GOTV Method

Tulchin Research recently released a January poll of 500 Mississippians, a third of them African American, which found that 47% support Presley, four points higher than the current governor, Tate Reeves. Measuring turnout, however, is different from taking a poll early in the season. When a candidate is in an extremely close race as Presley is in, every single vote matters, even votes from poor people who do not always have internet access, cable or mobile phones.

For example, in Espy’s 2020 Senate race, I tested the old-fashioned GOTV method in a low-turnout, high-poverty, largely African American precinct in Washington County, without VAN. Other precinct volunteers used VAN to guide their door-knocking to only the homes of residents who always vote and based on microtargeting tactics, such as identifying who drives sedans or watches MSNBC.

I recruited three young Black campaigners to door knock for five hours every day for three months in my adopted precinct. Including myself, the four of us left materials when potential voters were not home, but we retraced our steps and returned another day at a different time with hopes of meeting and convincing them to register and/or vote.

When they answered the door, we urged them to vote because a vote for Espy was a vote against Trump.

Hearing the name “Trump” always got their attention.

Then the conversation began, sometimes longer than we wanted to hear about the arguably worst president in the nation’s history, but in those doorways stood votes for Espy and Biden. With their permission, we always planted a yard sign on their property.

As we know, Mississippi has been a Republican stronghold over the past decade. Trump won the top of the state ticket by 17 percentage points. Espy lost by 10% but exceeded Biden’s vote share by 3%. Meanwhile, my adopted precinct turned out 35% more votes than in 2016. The precinct next door, using the Mini-VAN app, gained only 25%. Most precincts gained even less.

Presley’s campaign should not be the only campaign in the country spending more time and money contacting unlikely voters face-to-face in low-turnout precincts, especially if Democrats want to keep the Senate and the White House and take the House back. Volunteers, paid staff and even candidates themselves must knock not once but two or three times to have engaging conversations with people who are being turned off, instead of turning out, in campaigns—local, state and federal.

The Talk at the Door

The key ingredient to bringing voters out of retirement is the talk at the door. Talking and getting potential voters to talk back requires lots of energy, time and patience, particularly when they say they do not trust anyone anymore in government.

Yet it is necessary if Presley wants the 10% Espy lost in his 2020 bid and Hood’s 5% loss in the race against Reeves. Presley will need specific reasons why Black and Brown people, struggling to take care of their children and grandchildren on top of paying the rent and groceries, should vote for him—not just the reasons to defeat Reeves.

The Reeves list is long: not doing enough to reduce corruption in federal-funding programs; providing funds for white neighborhoods to build and improve infrastructure, but without the same enthusiasm for Black neighborhoods; and ignoring the plight of low-income families, especially single women with children. The list is longer than just those three items, too.

Sadly, Presley is not pro-choice regarding abortion rights but, like it or not, he must talk about the choices he will make as governor to revive the economies of some of the poorest cities and towns in the country, right here in Mississippi. Greenville is one of them. Again, I saw it up close. He may or may not do enough, but his tenure could easily do more than Haley Barbour, Phil Bryant and Tate Reeves have done for Mississippians.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Journalism and Education Group, the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.

Editor’s Note: Karen Hinton serves on the Mississippi Free Press advisory board.