Glen Conley had just parked his Nissan vehicle outside his workplace, Supreme Healthcare Corporation, in Houston, Texas, in August 1997, when two men followed him inside. “Glen Conley, I have a warrant for your arrest. You’re wanted for capital murder back in Mississippi,” one of the men said, as Conley related to the Mississippi Free Press by phone from the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss., in May.

“Hands on the wall,” the man that told Conley about the warrant for his arrest continued that August.

The other man placed handcuffs on him.

“Is this some kind of joke?” Conley says he asked the men.

“No sir; no joke,” the other responded, holding up the warrant for Conley, who was 25 at the time, to see.

The officers then took him to the downtown Houston jail to await extradition back to Mississippi where he was under indictment for capital murder for drowning a little girl he believed to be his daughter—a tragedy he says was an accident. Regardless, he believes he now has a right to parole after decades behind bars, but the State of Mississippi refuses to grant it.

An Outing to Percy Quin State Park

The indictment that then-Pike County Circuit Judge Keith Starrett, now 71, read to the jury during Conley’s trial in 1998 said he faced two charges. “Ladies and gentlemen, to give you a little background in this case, it’s alleged on or about this day, the 21st day of May, 1994, Mr. Conley did kidnap (a mother and her daughter) and bring them to Pike County from the State of Louisiana,” the judge said. Starrett is now a U.S. Southern District of Mississippi Court senior judge.

“It’s alleged that while this kidnapping was in process that the victim … was killed and murdered; It’s alleged that this occurred at Percy Quin State Park (in Pike County, Miss.) about, well, almost four years—a little over four years ago.”

At the time of the incident, Conley said that he believed he was the father of the 3-year-old girl, and he was taking her and the family out on an outing when they were in a boat accident, and the girl died.

The jury would eventually find Conley guilty of the charges after a five-day trial from June 29 to July 3, 1998. The judge sentenced him to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole or any other form of early release.

Conley maintains his innocence and, at the least, believes he deserves parole.

‘Just That One Night’

Glen Conley, now 52, graduated from Ponchatoula High School in 1987, immediately joined the U.S. Army, left three years later and subsequently met with a former female schoolmate. Ponchatoula is in Louisiana’s Tangipahoa Parish, which shares a border with Pike County.

“I saw her one night after I came back from the Army,” Conley said of the deceased girl’s mother during a phone interview with the Mississippi Free Press in May 2022. This reporter could not establish contact with the woman for comments and therefore replaces her real name with “Lillian” in this report.

“I went by a club, had been drinking, and I ended up going to a hotel with her, and you know, just that one night we spent together at the hotel,” Conley said of the encounter.

Within the next year, Lillian gave birth to a girl, whom this report refers to as Teagan to protect her privacy. Lillian told a mutual acquaintance that Conley was Teagan’s father. On learning the information, Conley immediately set out to meet Teagan.

“Really, why you never said something to me?” Conley remembered asking Lillian at the time. “I love kids, you know, and you never said nothing to me.”

Conley decided to become involved in Teagan’s life. “I started to spend time with (her), pick her up; I had to give (Lillian) money to make sure that she was comfortable and everything,” he told the Mississippi Free Press.

A Fatal Trip to Percy Quin State Park

On May 21, 1994, when Teagan was 3 years old, Conley took her, her mother, her two brothers, a cousin and two others on a 60-mile journey from Tangipahoa Parish to Percy Quin State Park in Pike County. The Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks markets the facility as “just one-and-a-half hours from New Orleans.”

“All of us were from Louisiana, and we live close to the Mississippi state line,” Conley said. “Lots of people from my area in Louisiana would drive the 45, 50 minutes to this park in Mississippi.”

“And so we had all been there before, to the same park, and on this particular day, we decided to rent paddle boats, which is something I always do,” he added in regard to the Saturday outing at the park. They went on the 490-acre Lake Tangipahoa at the park.

Conley, Lillian, Teagan and one of Teagan’s brothers were in one boat, while the rest were in the other.

On the stand as a witness at the trial in June 1998, Lillian said that she agreed to go to the park with Conley but did not want to go into the water, but he insisted. When she asked him to go back, he did not agree.

During the excursion, Teagan’s brother fell into the water. Conley got him back into the boat, but they soon discovered that Teagan was no longer aboard. Conley jumped into the water after her but did not successfully bring her back.

“After (Conley) came up, (he) said, ‘I couldn’t save (her), but here’s her lifeguard jacket,'” Lillian told the court during the trial.

Then-Pike County Assistant District Attorney Williams Goodwin told the court at the trial that Conley was deceitful and “committed the perfect murder” to benefit from hundreds of thousands of dollars in life insurance he had taken out on Teagan several months earlier.

“And we believe that all of the evidence will show that that man sitting right there—–that man sitting right there—killed a little 3-year–old girl to collect $200,000 worth of insurance (with State Farm) and that he is guilty of kidnapping and capital murder,” Goodwin told the jury.

Conley later told the Mississippi Free Press that Lillian wanted him to put aside some money for Teagan, and they had decided to set up a college fund. He said an acquaintance who was an insurance stockbroker told him, ”‘if you purchase a life insurance policy at this age, it can convert when she reaches that (college) age, and it will be worth a whole lot more than if you just buy a college fund (now).’ And so that’s what I did,” he told the Mississippi Free Press.

In his opening statement at the trial, prosecutor Goodwin accused Conley of using “trickery and deceit” by “getting them up to Percy Quin” and refusing to return Lillian and Teagan to dry land “after she begged him to.”

“[W]e believe the evidence will show that that constitutes kidnapping under the law,” the assistant district attorney said.

Conley’s county-appointed defense attorney, Meredith A. Bass, argued that the evidence showed Conley had “made numerous attempts to dive back under this water and could see nothing.” He said another boater picked Conley up and also attempted to help him with the search.

“Nobody could find this child,” Bass said.

Later in the trial after the defense rested, Bass argued for a directed verdict. In a directed-verdict request, the defense asked for a dismissal, citing the weakness of the prosecution’s case.

Bass said the prosecution had not argued any element of kidnapping under state statute.

“Your Honor, the State has wholly failed to prove the evidence of kidnapping” and provided “no evidence of secret confinement nor was there credible evidence that the alleged victim was unlawfully or forcibly restrained by the defendant,” Conley’s attorney said.

The assistant district attorney disagreed, arguing that the state’s position was that when the “child was pulled under the water at Percy Quin State Park on May 21st, 1994, that that child was held with force and in a (hidden) place, that child was being kidnapped at that moment.

“I think that the Court could assume that if that 3-year-old child had known that she was fixing to be murdered, she would not have gotten in that boat, or would have fought as much as a 3-year-old child can fight to resist,” he added.

Conley told the Mississippi Free Press that the prosecution used the insurance story “to try to make it look like something it wasn’t.” The accused got a call on Monday, May 23, 1994, where someone told him that the little girl’s body “has surfaced,” on Lake Tangipahoa, he told the Mississippi Free Press. That was two days after the trip.

Then-Pike County Coroner Percy Pittman, who died in 2018, said at the trial that he “retrieved the body at that time, which was in a prong position, face down, in the water.” He was not a medical doctor, but at the time of the incident was a retired police officer and registered emergency medical technician. He referred the case to then-Rankin County Deputy Coroner Dr. Steven T. Hayne, who later as the state pathologist faced immense controversy over his findings in numerous cases, reported heavily by journalist Radley Balko and others including the Jackson Free Press. At the trial, Pittman said he normally makes autopsy requests to Hayne.

The Mississippi Free Press obtained a copy of the autopsy from a source who asked not to be identified dated May 23, 1994, which indicates that the cause of death was “fresh water drowning” and the manner of death was labeled as an “accident.” A copy of her death certificate described it as a “boating accident.”

Even though he was known for providing what was often called questionable evidence to help with prosecutions, Hayne’s comments in the 24-page autopsy in 1994 indicated no evidence of foul play. “The decedent was noted to succumb secondary to fresh water drowning,” he wrote. “The decedent was riding in a boat when she fell from the boat.”

Then-Pike County Coroner Pittman requested that the Rankin County coroner explain the cause of death.

“The decedent was wearing an adult-sized life jacket, and the decedent is noted to have separated from the jacket when the decedent fell into the water,” Hayne stated. The autopsy included a picture of the life jacket that Teagan apparently had been wearing.

Conley told the Mississippi Free Press that one park ranger named Earl Wiggins told him, “all the jackets, all four of the jackets, were adult life jackets.” He said Wiggins “died in December of 1996; suddenly in ‘97, there is an indictment on me.”

Conley moved from Louisiana to Houston, Texas, in 1995 where he worked at Supreme Healthcare Corporation, Conley said.

In August 1997, Conley graduated with a nursing degree from San Jacinto Community College in Pasadena, Texas, and days after, law-enforcement officers arrested him following an indictment for capital murder back in Pike County.

‘She Deliberately Lied to Me’

“The indictment charged me (for) capital murder with the underlying felony of the kidnapping of (Teagan),” Conley later told the Mississippi Free Press in May. “No witness (at the trial) ever said that they were kidnapped.”

One year after Conley’s arrest and extradition to Mississippi, then-Pike County Circuit Judge Keith Starrett presided over the trial in 1998.

At the trial, Conley said he discovered something he did not know before. “The interesting thing is that (Lillian) led me to believe that I was (Teagan)’s father, and I took her word, but at my trial, man, at my trial,” he repeated exasperatedly over the phone, “I found out that not only am I not (her) father but that she knew I was not (her) father and that (her) father was incarcerated for not paying child support.”

“So she knew this. She deliberately lied to me, saying that I am the father of her child, and she knew better because another man (was) incarcerated for not supporting the same child.”

At the end of the trial, the jury found Conley guilty of capital murder.

“All right. ladies and gentlemen, the instructions state there are two options in a capital murder case: The death by lethal injection or life without parole,” Judge Starrett said, according to a transcript of the proceedings the Mississippi Free Press obtained for this report.

Sometime later, the circuit clerk read that the “jury was unable to agree unanimously on punishment.” At this point, it became the judge’s decision.

“I am truly not guilty of this crime,” Conley told the judge before his sentencing on July 3, 1998.

Starrett announced that he was sentencing the man “to serve the remainder of your natural life in the state penitentiary without the benefit of parole or probation or early work release.”

Conley Zooms Into Academic Conference

While in prison in 2016, Glen Conley served as the facilitator of a book club in Walnut Grove Correctional Facility, Walnut Grove, Miss. and in 2018 founded a book club at the Wilkinson County Correctional Facility in Woodville, Miss., and was working on a book of poetry. At Wilkinson, Conley learned of Binghamton University in New York history professor Leigh Ann Wheeler.

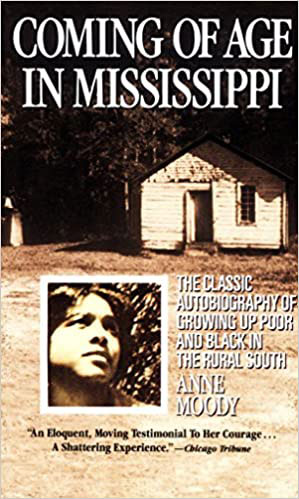

For 30 years, Wheeler has been studying and teaching the 1968 memoir of the late Anne Moody, titled “Coming of Age in Mississippi,” and has now embarked on writing the civil-rights icon’s biography. Moody was born in 1940 to sharecroppers in Wilkinson County, Miss. She attended Tougaloo College in Jackson in 1961, and was a civil-rights activist, including in Canton. She died in 2015.

A few years back, Wheeler learned that Wilkinson County Correctional Facility Chaplain Dr. Roscoe Barnes was leading a book group on Anne Moody. She sent the group 50 copies of “Coming of Age in Mississippi.”

“It was through my work on Anne Moody that I connected with people at Wilkinson County Correctional Facility, which is where Glen was in prison at the time, and in 2018, he learned about my work,” Wheeler told the Mississippi Free Press by phone in May 2022.

Conley learned from Barnes about Wheeler’s ongoing work on Moody’s biography and reached out to her in 2018, asking her to write the forward to his poetry book, “Reflections in Black: Remembering Anne Moody and Others Who Paved the Way,” which he published later that year.

Wheeler invited Conley to present his research on Anne Moody at the Western Association of Women Historians Conference in April 2021, held over Zoom.

“He’s the first incarcerated person in the state of Mississippi to be allowed to do that,” the professor told the Mississippi Free Press. “He did an amazing job. Awesome.” When a group of history professors, including Wheeler, hosted a scholars’ workshop on Anne Moody on May 18, 2022, over Zoom, Conley participated in that virtual event as well. On Oct. 12, 2022, Conley and Wheeler gave a joint presentation at the National Conference on Higher Education in Prison.

Earlier in 2022, Wheeler and three others opened an account on fundrazr.com to raise funds for Conley’s defense under the #JusticeforGlen hashtag. They argued that his conviction was wrong in a 2,000-word explainer and have raised $4,800 to date.

“We are committed to securing Glen’s freedom and helping him join the more than 3,000 wrongfully convicted people who have been exonerated since 1989,” the fundraisers said on the website. “Revisiting 25 years of motions and appeals will require countless billable hours. Attorney fees for a new trial will cost even more.”

Trial Judge: ‘I Have No Jurisdiction’

In 2014, Glen Conley earned a bachelor’s degree in Christian missions from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. He presently works as a pastor and is pursuing a master’s degree in theological studies from Nations University in New Orleans. “Now I’m a pastor, I’ve been to Bible college, and so that’s what I do (in prison),” he told the Mississippi Free Press.

Conley says his 1998 conviction was incorrect as a matter of law, not just because he is innocent of the crime. He made his opinion known to Judge Starrett in a letter he wrote to him on Sept. 29, 2021, after spending 23 years in the Mississippi Department of Corrections’ custody.

In a phone conversation with the Mississippi Free Press on Oct. 18, 2022, Judge Starrett, after saying he remembers Conley, recalled that the jury did not reach a decision to purnish Conley with a death penalty. “So he got life without parole; He was guilty of capital murder,” he added.

Regarding his correspondence with Conley, the judge said, “I don’t remember it. I may have, but I don’t remember it.” Responding to the fact that Conley said that the judge ruled wrongly, Starrett said, “I didn’t say that; that’s what the law requires.”

Conley wrote in the letter the Mississippi Free Press acquired, “I know that a jury decided my guilty verdict. However, the jury did not decide my sentence, you did.”

“According to MS statute 99-19-101(3)(c), if after the trial of the penalty phase, the jury does not make the findings requiring the death sentence or life imprisonment without eligibility for parole or is unable to reach a decision (emphasis added), (the) court shall impose a sentence of life imprisonment,” he wrote, citing the law. He argued that the court does not have the authority to add “without eligibility for parole,” as part of his sentence.

“The law is clear in this regard,” Conley explained. “It is not a discretionary matter. Yet, each time I raise this issue, the M.S.S.C. (Mississippi Supreme Court) turns a blind eye at justice by barring it from review under res judicata,” Conley continues in the letter.

Res judicata is Latin for “a matter decided” and generally refers to the principle under which the court rejects relitigating a cause of action already judged on the merits, Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute explains.

On Nov. 1, 2022, the Mississippi Supreme Court agreed to the resentencing of another MDOC inmate, 59-year-old Billy Ray Harris, sentenced in 2001 to life without parole for committing the offense described as depraved-heart murder against a Madison County man in 1999. In April, Harris petitioned the court to demand that the Madison County district court resentence him. In a court filing on Sept. 12, 2022, the Mississippi attorney general agreed that the court should overturn his “life without parole sentence and remand to the trial court for resentencing consistent with the statute” because “Petitioner should have been sentenced to a maximum term of life imprisonment.”

In his September 2021 letter to Judge Starrett, Conley wrote, “Your honor, I implore you to ascertain the correction of this erroneous sentence. Your honor, for what it’s worth, I am not guilty as charged. Again, I understand that the jury decided my trial outcome, not you.”

“However, with all due respect, my sentencing fell within your hands once the jury failed to reach a decision as to sentencing,” he added. “I truly believe that you made an honest mistake. I should have been eligible for parole over 14 years ago, but instead, I have spent the last 23 years illegally sentenced; Your honor, please see to my sentence being corrected.”

The judge later replied to him in a letter dated Oct. 7, 2021, which the Mississippi Free Press obtained for this report. “I read your letter and don’t remember the exact circumstances of the sentencing, but I do remember that the jury was unable to reach a verdict on the death sentence. I have now left the State system and have no jurisdiction over your case,” the judge wrote.

What Does Parole-Reform Law Say?

In 2021, the Mississippi Legislature passed and the governor signed into law Senate Bill 2795, the Mississippi Earned Parole Eligibility Act, giving capital-murder offenders the opportunity for parole if the offense happened before “July 1, 1994.”

Mississippi State Senate Corrections Committee Chairman Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, sponsored the bill. He told the Mississippi Free Press on Oct. 14, 2022, that he expects those people covered to have already received parole. “The law goes all the way back to 1994 … those people are eligible for parole, and most of them should have already gotten out because of the new sentencing law,” he said.

The bill supposedly granted “capital offenders” eligibility for parole except for “[a]ny offense to which an offender is sentenced to life imprisonment without eligibility for parole under the provisions of Section 99-19-101, whose crime was committed on or after July 1, 1994,” the law states.

Conley believed that was a lifeline for him, considering that Teagan drowned in May 1994.

In November 2021, Conley petitioned the Mississippi Department of Corrections to grant his appearance before the parole board, about four-and-a-half months after the law went into effect on July 1, 2021.

During his interview with the Mississippi Free Press, Conley explained the basis for his request: “The revised parole statute 47-7-3 that went into effect July 1st, 2021, it mentions people with natural life sentences and people with capital-murder charges, and according to that statute, anyone is eligible for parole, with a capital-murder charge or a natural life sentence except those who are convicted and sentenced for a crime that occurred on or after July 1st, 1994,” he said. “Since my occurrence happened prior to that date, I’m not exempt from parole.”

“So (basically) the statute says, look, no matter what your sentence (is,) you’re eligible for parole, except ‘these people’, and I’m not included in that except-ance,” he added. “So I’m arguing—look, here’s the law, my situation happened prior to this date; I should have parole.”

The Mississippi Department of Corrections disagreed with Conley in a response around Dec. 30, 2021: “Your file has been returned; your order states without the benefit of parole,” in reference to his sentencing order.

In his subsequent request for review, Conley wrote, “Regardless of my sentencing order, a new law has been passed that gives parole eligibility as long as the offense was committed prior to July 1 (1994); Mine is May 23, 1994,” he wrote on Jan. 21, 2022. MDOC responded on Feb. 7, 2022, simply stating, “You do not qualify for a parole date.”

In March 2022, Conley, who was in the George County Regional Correctional Facility, sued MDOC at the George County Circuit Court. The case is now before Circuit Court Judge Robert P. Krebs. Conley is now at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss.

Conley asked the judge in his filing to “correctly classify his eligibility and require the parole board to consider him for parole.”

“The trial court exceeded its sentencing authority by sentencing Conley to Life Without Parole, in that only a unanimous jury had the authority to impose such (a) sentence,” Conley’s lawyer Michael W. Crosby argued in the court filing.

When the Mississippi Free Press called the 14th District Attorney’s office on Oct. 5, 2022, to ask about Conley’s lawsuit, Assistant DA Robert W. Byrd said the office “can’t give a comment on specific cases.” The district contains Lincoln, Pike and Walthall counties.

In April 2022, Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch filed a brief opposing Conley’s request. She wrote that Conley is not eligible for parole under the new law and that the Mississippi Supreme Court has rejected his argument against his original sentencing order. No new developments have emerged in the case since her filing.

“Petitioner is ineligible for parole under the current version of the parole eligibility statute, Miss. Code Ann. § 47-7-3, effective as of 2021, as this statute did not make persons that committed capital murder that were convicted and sentenced to life without parole prior to July 1, 1994 eligible for parole,” Fitch argued.

“The parole statute does not clearly and unequivocally express that it intends to allow parole eligibility for offenders with previous capital offense convictions and sentences of life without the benefit of parole that were committed prior to July 1, 1994, as it is silent on such, nor does the Petitioner provide any authority to suggest otherwise,” she continued.

“The parole statute, as amended by the Legislature in 2021, is silent on allowing parole eligibility for offenders with previous capital offense convictions and sentences of life without the benefit of parole that were committed prior to July 1, 1994.”

After reading the Mississippi Attorney General’s argument that Special Assistant Attorney General Tabatha Baum filed, Conley disagreed. “They are arguing that I’m not entitled to parole because the statute doesn’t explicitly state that I am. But in fact, the statute does,” Conley told the Mississippi Free Press.

Conley bases his opinion on the first portion of the parole act, which states: “Every prisoner who has been convicted of any offense against the State of Mississippi … may be released on parole.” It lists the following exceptions: habitual offenders, sex offenders, those convicted of human trafficking offense committed after June 30, 2014, those with drug trafficking convictions, those with the conviction of first-degree murder committed after June 29, 1995, second degree murder convicts, and those sentensed for capital murder offenses committed after June 30, 1994.

Conley believes those exceptions do not apply to him.

Professor: ‘Glen’s Case is a Product of a World I Know’

Retired University of Minnesota history professor Sarah Evans is on the #JusticeforGlen team, working to raise money for Glen’s defense.

Evans explained her involvement with the fundraiser in a post on the fundrazr.com platform. “I grew up in South Carolina in the 1950s and have vivid memories of the segregated world filled with ‘white only’ signs on restaurants, water fountains, and restrooms and city buses where black people were forced to sit in the back,” she wrote. “As a child, my parents were the only white people I knew who believed segregation was wrong.”

“Glen’s case is a product of a world I know, where racial hierarchy is enforced with violence inflicted both by the structures of public authority (courts, government) and everyday ‘rituals of humiliation,'” she added. “As a southern white woman and a scholar I am constantly struck by what difficult and slow work it is to change patterns that are rooted in centuries of slavery, segregation and economic inequality. This case is close to my heart.”

Leigh Ann Wheeler, the Binghamton University professor, told the Mississippi Free Press that Conley’s story moved her after she met him in 2020.

“After I met him in March (2020), I walked out of that prison sobbing; it has haunted me ever since,” she said. “I had felt pain from that ever since, and the only thing that helps is to be trying to get him out.”