Editor’s note: The following article talks about domestic violence and may be difficult for some readers. The Office Against Interpersonal Violence within the Mississippi Department of Health maintains a hotline for people experiencing domestic abuse. Those who need help can call 1-800-898-3234 or 601-981-9196.

Hayden stood in her home, clutching a shard of broken glass so tightly that her hand began to bleed. In front of her stood her husband, who moments before punched her in the face after she confronted him about sleeping with another woman.

“I was just that angry and wanted to see blood come from him because I had got to a point that I was just tired of him hitting on me,” she said.

Reining in her fury, Hayden did not counterattack. The next morning, she called her brother and aunt, who told her to “leave him and never look back,” telling her that her mother “would turn over in her grave” if she knew Hayden was being abused.

She did, and she married her current husband two years later. The pair have been happily together for 28 years.

“I do believe now it was God that kept me from cutting him because I would probably be in jail now ’cause of the rage that was in me that night,” Hayden said.

Living in a small Mississippi River town, Hayden endured her then-husband’s cruelty because for a while she adhered to the belief that domestic abuse is something to be hidden from the broader community and kept within the confines of the household.

That mindset is frequently found in rural communities, where domestic violence often goes unchecked not only because of that belief but also isolation, lack of transportation and access to resources and personal support systems.

Hayden, who asked to go by her last name for safety concerns, grew up with her parents and two brothers in the type of town where “everybody knows everybody.” After Hayden’s mother died young, she was raped multiple times—she would not say by whom. That trauma, she said, culminated in years of self-hatred that led to her entering unhealthy relationships.

While in her early 20s, her first marriage lasted six months, and her next relationship, in Illinois, was emotionally and mentally abusive. When she returned to her Mississippi home, she met her second husband, who quickly convinced her to marry in Memphis. The marriage immediately devolved into emotional and physical abuse, she said, often while he was intoxicated.

“Each time he would say he was sorry, and I believed him, but he would always end up doing it again,” Hayden said. “It got so bad that I would have black eyes going to work.”

She said administrators from her job as a factory worker would try to convince her to leave, but Hayden was committed to staying loyal to her marriage vows.

“I never reported any abuse because I always believed what goes on in a person’s house should stay in the house,” she said.

‘Wow, You Done Shot Me’

Within such close-knit towns, the stigmatization of domestic violence makes women in those areas more vulnerable to abuse. Compounded with a lack of resources in comparison to more urban areas and the logistical challenges of living in isolated areas, rural women face both increased rates of domestic violence and challenges if they choose to report the abuse.

A 2011 study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the most current available on the subject at the time of this original writing, concluded that women in small rural and isolated areas reported the highest prevalence of intimate partner violence (up nearly 23% compared to 15.5% for urban women).

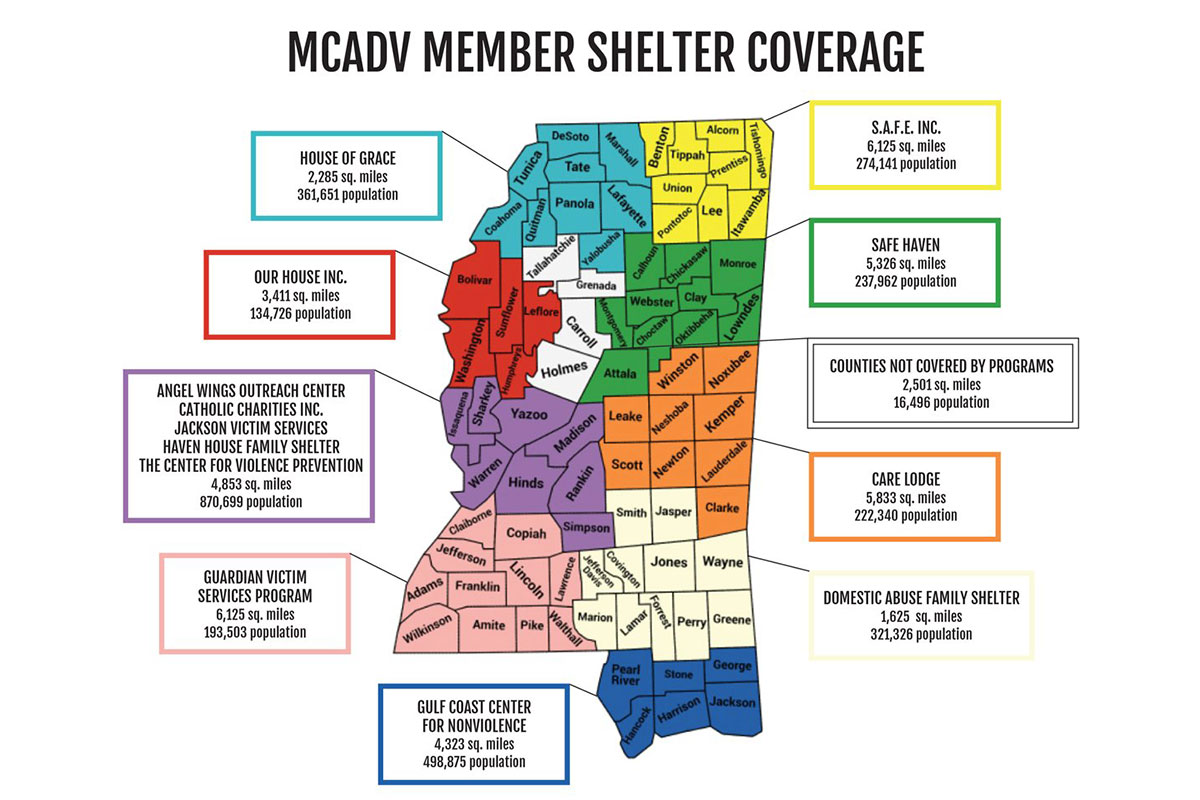

Rural women also reported significantly higher severity of physical abuse than their urban counterparts. The mean distance to the nearest domestic violence resource was three times greater for rural women than for urban women, and rural domestic violence programs served more counties and had fewer on-site shelter services. Additionally, more than 25% of women in small rural and isolated areas lived more than 40 miles from the closest program, compared with less than 1% of women living in urban areas.

Hayden’s ex-husband’s abuse escalated when he shot Hayden in the arm with a gun. “He seemed surprised, himself, that the gun went off,” Hayden said. “I fell to my knees and told him, ‘Wow, you done shot me.’”

Officers arrived at the hospital to question Hayden about the incident.

“I made up an excuse for him, saying that he was just taking the gun out, and it accidentally went off and shot me in the arm,” Hayden said. “I was protecting him and not thinking about my own feelings. I knew they would arrest him and put him in jail.”

Despite suffering from abuse, Hayden never called the police on her ex-husband, explaining that in her small town, “Everybody knows everybody,” and that she did not want her personal life to be the topic of conversation for others. Sometimes, neighbors would hear the two of them arguing, but none ever called the police, either. Instead, they would tell her family members.

Before Hayden’s arm fully healed, he abused her again. The physical violence continued, and her husband convinced Hayden to move to a different, unfamiliar town, away from her friends and family. Hayden left him and returned multiple times, until she answered a call from the mother of another woman he was seeing, leading to the confrontation that ultimately convinced her to leave him for good.

Isolated Inside a Culture of Closeness

Pat Davenport, the executive director of Our House, a rural, community-based domestic violence program in Greenville, Miss., said domestic abuse is often not hidden in the town’s rural community since everyone is so connected. Moreover, he says it is instead much more accepted and seen as “a family matter.”

Law-enforcement officers also, Davenport observed, are often not trained to be as culturally sensitive to those facing abuse as officers in more urban areas may be, meaning they might not handle intimate partner violence well, sometimes suggesting that survivors should just “suck it up” or that they could easily leave. She also noted that these issues are compounded for women of color or LGBTQ+ women who domestic violence already disproportionately affects.

A consequence of rural connectedness is that law-enforcement officials are frequently related to or know the perpetrators. On occasion, Davenport said, the abuser may be a law-enforcement officer, which can further complicate how the issues become addressed and resolved.

Regan Hadaway, police chief in Raymond, Miss., acknowledges that those on the force have “certainly known previously people who have been involved in domestic-violence situations,” he said.

The chief said domestic-violence calls are relatively infrequent, sometimes occurring months apart, potentially pointing to the reluctance to report.

Davenport noted that while rural communities have a culture of connection and closeness, people living in those areas may also face isolation.

Rural communities often have fewer resources than their urban counterparts, Davenport said, which means some homes might not have internet access, and women may struggle to know which resources are available. If the nearest home is acres away, then neighbors might not be aware of what is happening.

Geographical and Financial Barriers for Help

Wendy Seals, executive director of Angel Wings Outreach Center, a shelter and domestic-violence support center in Mendenhall, Miss., said they have served victims who do not even have cell phones.

“They pretty much rely on a family person to help them,” she said.

Hayden’s experience, in which her abuser moved her to an area isolated from friends and family, is a common abusive tactic in rural communities, Davenport said, as they can sever victims’ connections to the people who might be able to intervene.

“If there are no neighbors close to her, if (the abuser) stops her from going to the grocery store, churches, (then the domestic violence may continue further as) those are places where people can observe and inform a survivor that there’s help out there,” she explained.

From a logistical level, someone trying to escape abuse in a more rural area also faces infrastructure barriers. For example, the nearest shelters may serve many rural areas at once and can thus be farther away from certain victims who need assistance. High gas prices can deter survivors from driving to shelters, and shelters and domestic-violence programs may lack the funds or resources to transfer survivors directly.

Our House recently relocated a survivor to a shelter five hours away, which cost $450 in transport—a generally prohibitive amount and something that cannot be done regularly. The program only employs five people, meaning one employee may work with as many as 40 clients in a two-month period.

Seals added that the rural areas they serve encounter similar obstacles stemming from a lack of services.

“If a child is molested, they have to go to Jackson, (which is) like 40 miles away,” she said. “Physicians don’t come down to us; we have to go to them.”

Organizations and shelters such as these are not the only ones lacking the resources needed to further combat domestic violence.

Anthony Shelvy, a social worker at Jefferson Comprehensive Health Center in Fayette, Miss., said the center has few resources for helping the domestic-violence victims it sees. Located in southwest Mississippi, the county has a population of less than 8,000, almost 40% of whom live below the poverty level.

“We don’t have as many resources as other counties,” Shelvy said. “Natchez has a safe house, and I know they service this area, also, but it’s a drive. I wish we had the resources and have those people that want to put in the efforts.”

Shelvy said the health center sees very few domestic-violence victims, since most people would go to the emergency room for injuries instead. Looking at the county as a whole, Shelvy said Jefferson County could help more people if it had more resources and could provide more counseling services.

As of now, the county’s crime-victim agency, which focuses on domestic violence, only has two people to cover the entire county, Shelvy noted. “Two people (are) working for a (527-square mile) county that has no resources to combat the issue,” he said.

Shelvy added that the area also lacks housing and healthy food. Having those resources as well, he believes, could help promote better living and subsequently counteract cycles of violence.

“We have the buildings; we just need efforts,” Shelvy said. “If I knew how to do it, I would.”

Click here for Information about domestic-violence laws in Mississippi. For more information on domestic-violence resources available to Mississippians, visit mcadv.org.

The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting published the original version of this article. Sign up for their newsletter here.