I have heard all kinds of things concerning Emmett Till’s case as of late. It seems that in 2022, Till has yet had the opportunity to rest in peace.

Till’s peace has and still seems to be a long time coming. His life was violently cut short after Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam abducted him from his great-uncle Moses Wright‘s house. These white men tortured and lynched a 14-year-old child.

When his body was found in the Tallahatchie River weighed down with a 75-pound cotton gin, it was brutally beaten and broken. The ring on Till’s middle finger bearing his father Louis Till’s initials “LT” was the only way his body could be identified. But his story did not end once he was interred on Sept. 6, 1955, at Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Ill., in a glass-topped casket his mother insisted on so the world could see what the racists had done to her son. Photos of Emmett Till’s mutilated body appeared in the Sept. 15, 1955, issue of Jet Magazine.

| Emmett Till was brutally killed in the summer of 1955. At his funeral, his mother forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism by having her son placed in a glass-topped casket. Courtesy TIME |

In 2001, Burr Oak Cemetery came under the direction of Carolyn Towns and the cemetery promised Till-Mobley that they would build a museum, the “Emmett Till Historical Museum,” to honor Till’s legacy. The museum never happened. Due to a dispute over the identity of the body, which in 1955, provided the jury legal reason to acquit the murderers, the FBI reopened the Till case in May 2004. The Cook County Medical Examiner set up a tent at Burr Oak Cemetery to exhume his body and cemetery workers confirmed then that Till’s plot was not harmed, but Towns clearly neglected his casket.

On June 1, 2005, Till was exhumed again for an official autopsy and to compare his DNA to a female relative on Till’s mother’s side to confirm his identity. Four years later after the exhumation, the casket was found “tattered, dented, and rusty” in a garbage-strewn storage shed Frank James reported in an NPR article published on July 10, 2009. Because of the original casket’s condition, state law required that his body be re-buried in a new casket. This action led to the glass-topped casket becoming “famous” once again as it was embroiled in its own bit of controversy.

Towns was charged with dismembering remains, reselling occupied plots and stealing over $100,000 from the cemetery. She pled guilty to a range of charges in 2011 and was sentenced to 12 years in prison that following November. Till’s casket is now on display in the “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Carolyn Bryant Donham’s Lack of Accountability

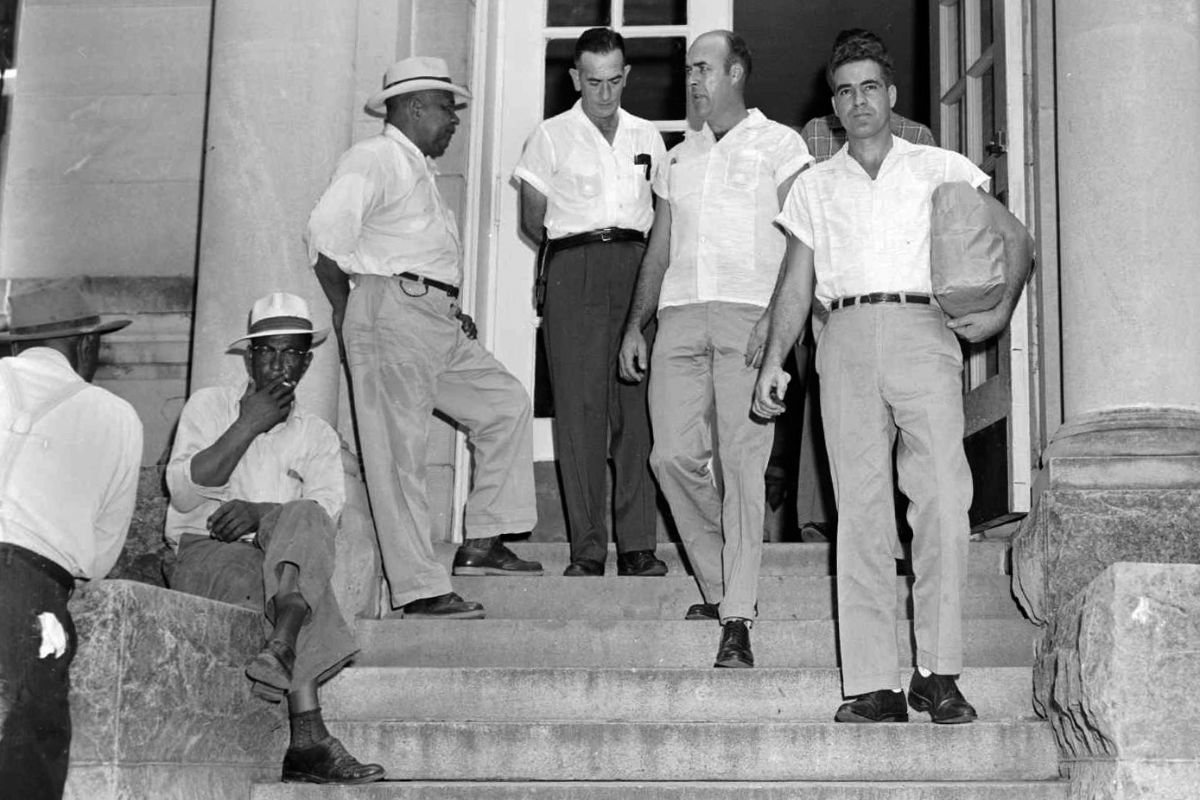

An all-white jury acquitted Milam and Bryant, the men who later admitted to killing the boy to Look magazine. That acquittal is the the single most egregious of all things related to this case, murder aside. A close second is Carolyn Bryant Donham’s complete lack of accountability.

Carolyn Bryant (then Roy Bryant’s wife) was working at the cash register of Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market. Till was alone in the store with Carolyn Bryant for less than a minute.

Over time, there have been many iterations of what happened in the store, including that Till grabbed her and was menacing and sexually crude. Timothy B. Tyson, Duke University professor and author of “The Blood of Emmett Till,” stated during an interview with Vanity Fair on Jan. 26, 2017, that Donham told him in 2007—at the age of 72—that she lied. “That part’s not true,” Tyson said she told him in the disputed interview. She has since denied confessing anything to Tyson.

Bryant was 21 at the time of Till’s murder and is now 88 years old. Many argue she is “too old” or that “too much time has passed” for her to be arrested and put on trial. However, there is a precedent for prosecuting Civil Rights Movement-era murderers, as in multiple cases where neither the age of the accused nor the amount of time passed had any bearing on murder, manslaughter or kidnapping cases with no statute of limitations.

Byron De La Beckwith Jr. was an American white supremacist and klansman from Greenwood, Miss., who assassinated civil-rights leader Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963. Two trials in 1964 on that charge, with all-white Mississippi juries, resulted in hung juries. Thirty-one years later, in 1994, the state tried Beckwith in a trial based on new evidence, and a mixed-race jury convicted him of murder and then sentenced him to life in prison.

Edgar Ray Killen was 80 when a Neshoba County jury in Mississippi convicted him of manslaughter for masterminding the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in 1964 there. James Ford Seale was 72 when a federal jury convicted him of kidnapping charges (possibly due to the crossing of state lines during the crime) in the deaths of Henry Dee and Charles Moore in 1964. Both former Klansmen died in prison.

When there is not a clear legal means to prosecute as in some cold cases, there is a precedent for creating one as in the case with Nazi War criminals. Debbie Cenziper’s book, “Citizen 865: The Hunt for Hitler’s Hidden Soldiers in America,” highlights the investigation and conviction of Jakob “Jack” Reimer, a Nazi mass murderer. “Reimer’s presence in the United States is an affront to all those killed in the Holocaust,” Cenziper wrote. Reimer was 73 when the investigation into his past started, and his U.S. citizenship was revoked in 2002 due to his war crimes.

‘Weaponizing White Womanhood’

Carolyn Bryant Donham wrote an unpublished memoir, “More than Just a Wolf Whistle,” in which she positions herself as the victim. Her entire account of that one minute alone with Till, the trial, the “not guilty” verdict and every breath she has taken since then—to paraphrase Cenziper—is an affront to all those who have been killed in the name of white supremacy in America. It is enough to make a person’s blood boil.

A warrant issued on Aug. 29, 1955—remember, Emmett Till’s body was found at the bottom of the Tallahatchie River in northern Mississippi on Aug, 31, 1955—was found in the basement of a Mississippi courthouse in June 2022 revealing that Mrs. Bryant was named in the kidnapping of Emmett Till. This original warrant has not expired, and there is no statute of limitations on kidnapping.

White women have long been guilty of “weaponizing white womanhood” with “feminine fragility to act in a racist manner towards the people they are targeting,” as Megan Armstrong discussed in her paper, “From Lynching to Central Park Karen: How White Women Weaponize White Womanhood.” For those who believe there was absolutely no reason to prosecute Carolyn Bryant Donham, we now know sufficient evidence existed to arrest her for kidnapping—even under 1955 standards.

Felony murder doctrine is a rule of criminal statutes that any death occurring during the commission of a felony is first-degree murder, and all participants in that felony or attempted felony can be charged with and found guilty of murder. Even if the death was accidental, all of the participants can be found guilty of felony murder, including those who did no harm, had no gun and/or did not intend to hurt anyone. The kidnapping charge and the felony murder doctrine allows the full weight of Till’s murder to be placed squarely on Carolyn Donham’s shoulders—if local authorities indict and arrest her.

Dewayne Richardson, district attorney of the Fourth Circuit Court District of Mississippi, is front and center in this case.The discovery of the warrant and the silence of this office should move this case to the forefront of every advocate for justice and activist in this country, but a Leflore County grand jury declined to indict Carolyn Bryant Donham even after the warrant turned up. Civil Rights era murderers and accomplices still living among us should be hunted down in the same manner as Nazi War criminals.

Can this little loophole be the providence needed to finally get justice for Till?

Dr. Stacey Patton reminded us of the need for leadership here with a quote from Ida B. Wells: “Where are our ‘leaders’ when the race is being burnt, shot and hanged? Holding good fat offices and saying not a word.”

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.