Around this time last year, I was in the thick of preparing for my final exams at the University of Delaware. Meanwhile, I did a deeper examination of why I had decided to leave Mississippi, my home, and travel thousands of miles to a foreign, icy state for a graduate degree.

While I’d enjoyed my first year living in Newark, Del., and building a new network, I began questioning what drove me to leave. After all, Mississippi has a number of fine institutions that would’ve served me well. I was excited about returning home for the summer for an internship from Mississippi First, a nonprofit focused on educational advocacy.

As a former teacher, it was the perfect chance to connect with other teachers and educational leaders. I knew this networking would be critical if I had any aspirations of returning home upon completing my degree.At any rate, I was eager to learn how I could be a part of the coalition aiming to improve Mississippi’s educational outcomes.

‘We Need Talented People to Come Back Home’

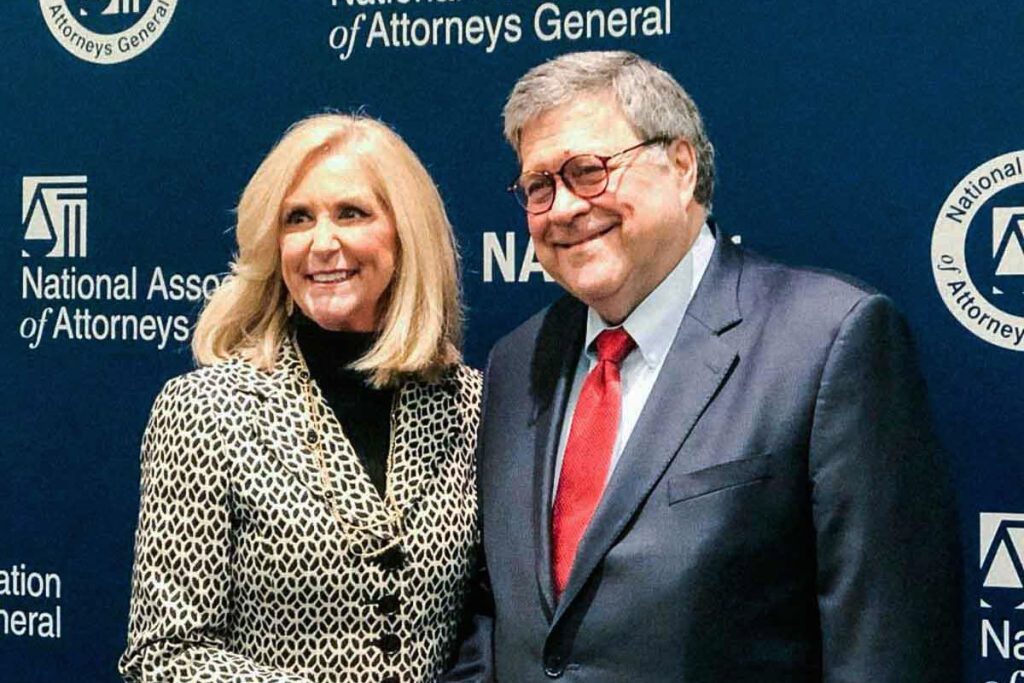

On a wet, summer morning last year, I got dressed in a pristine blue suit and darted out of my house to make an 8 a.m. appointment at Broad Street Café in Jackson. As I sat waiting, I recognized a familiar face: then-State Treasurer Lynn Fitch, who was then making a successful run for attorney general. This wasn’t my first encounter with her—I had met her while an undergrad at Mississippi State and reminded her of my name. She replied by congratulating me on grad school and uttered a few words that left a knot in my stomach. It was as if someone had poured a glass of water on my face.

“We need talented people to come back home and help improve our state,” Fitch said.

While some might dismiss her words as trivial or political rhetoric, I held onto them with agitation. Why aren’t our state leaders like Fitch making our state better for all of us?

Now, in the midst of our state’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, her comment pains me even more.

Fitch’s recent decision to file a lawsuit against China over COVID-19 contradicts her message to me. Her lawsuit against China “for the malicious and dangerous acts that caused death, health injuries and serious economic loss from the COVID-19 crisis” exacerbated my uncertainty that our state prioritizes all of its citizens, particularly those who are black and brown.

The attorney general claims that “China did the world a great injustice by engaging in a complex cover-up of the dangers of this deadly virus.” I would argue that Gov. Tate Reeves’ delay in making a stay-at-home order was more unjust and outright careless.

Recently, Fitch backed away from an effort to release pretrial detainees in order to prevent the spread of the virus in Mississippi. Her action will inevitably affect people of color at a disproportionate rate. And in a state that has seen black people make up a strong majority of COVID-19 deaths, we have to pay attention to the ways leaders like her are continuing to perpetuate a system of oppression.

Confederate Proclamation Shows Lack of Empathy

When we as citizens elect someone to public office—school board, city council, governor, president—we are asking them to represent all of us, our interests and communities. If those you represent do not believe that you can act on their behalf, as an ally with their best interests at heart, then we must speak up and hold them accountable.

Furthermore, symbols matter. Reeves’ decision to declare April as Confederate Heritage Month demonstrates his lack of empathy during a time of urgency. The message he sent didn’t just represent a heritage or a romanticized past; it represents a state whose values run counter to what its young people, like myself, are struggling to manifest in Mississippi.

As I drove home later that day, I mulled over whether to accept Mississippi First’s internship opportunity and do what I was looking forward to all year—be an advocate on behalf of children in my home state or accept the Southern Poverty Law Center’s offer to do the same in Alabama.

Although I yearned to stay, save a little money and work for Mississippi First, I couldn’t help but reflect on the comments Fitch had made to me earlier that morning. I considered the years of injustice Mississippi’s government has inflicted its most marginalized groups. I questioned why I should return to a state that has over and over demonstrated a lack of concern for its most vulnerable populations.

In the end, I accepted the SPLC’s offer and worked in Alabama that summer.

If our state is serious about retaining its pool of young and ambitious talent, its public officials must advocate for all its people. The handling of COVID-19 is leaving young people, like myself, skeptical about a return home.

As a future change agent, I am wondering how leaders in Mississippi will acknowledge the humanity of people of color during routine circumstances if they don’t in a time of crisis.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,000 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.