The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals voted to uphold a Jim Crow law that Mississippi’s white-supremacist leaders adopted in 1890 in an attempt to disenfranchise Black residents for life. White lawmakers designated certain crimes that they believed Black people were more likely to commit as lifelong disenfranchising crimes.

The court’s conservative majority admitted that the Jim Crow law was “steeped in racism,” but said the State had made enough changes in the 132 years since to override its white supremacist taint. A 2018 analysis found that the law still disproportionately disenfranchises Black Mississippians compared to white residents.

In a statement on Wednesday, the Mississippi Center For Justice, which filed the lawsuit against the State of Mississippi in 2017, said it will appeal the ruling in Harness v. Watson to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“This provision was part of the 1890 plan to take the vote away from Black people who had attained it in the wake of the Civil War,” said Rob McDuff, an attorney with MCJ who argued that the Jim Crow violates the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of Equal Protection under the law. “Unfortunately, the Court of Appeals is allowing it to remain in place despite its racist origins. Despite this setback, we will continue this battle and seek review in the U.S. Supreme Court.”

The 5th Circuit Court is based in New Orleans and handles cases from Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi. Republican presidents appointed most of its judges. The judges in Wednesday’s majority did not sign their names to the ruling on the voter disenfranchisement law.

‘To Secure The Supremacy of the White Race’

During the Reconstruction era, newly emancipated Black Mississippians made enormous gains as Black men gained the right to vote. But in 1890, white Mississippi lawmakers began drafting a new constitution riddled with Jim Crow laws. The new system instituted an explicitly white-supremacist regime, with its drafters bent on disenfranchising, criminalizing and denying opportunity to the state’s Black residents.

The legislative committee that drafted Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution was initially explicit in its white-supremacist goals. They adopted a resolution declaring that “it is the duty of this Com. to perform its work in such a manner as to secure permanent white rule in all departments of state government and without due violence to the true principles of our republican system of government.”

They later revised the resolution, changing “white rule” to “intelligent rule.” Contrary to popular misconception, Jim Crow laws usually masqueraded as colorblind. But on the floor of the Mississippi Constitutional Convention, lawmakers were open about their intent.

“I will agree that this is a government by the people and for the people, but what people? When this declaration was made by our forefathers, it was for the Anglo-Saxon people. That is what we are here for today—to secure the supremacy of the white race,” Franklin County delegate J.H. McGehee said to applause from his fellow lawmakers at the 1890 convention as he vowed to strip voting rights from Black residents “even if it does sacrifice some of my white children, or my white neighbors or their children.”

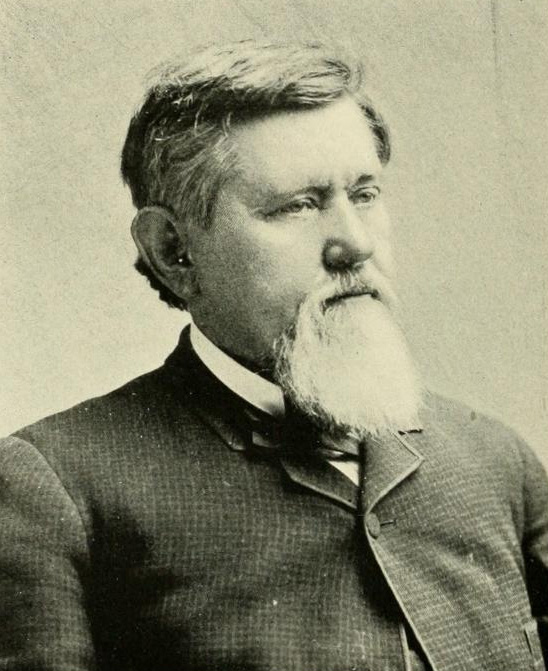

After the state adopted that law as part of its constitution, along with other provisions like poll taxes and literacy tests, James K. Vardaman, one of its drafters, explained the goal: “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter … Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the n–ger from politics. Not the ‘ignorant and vicious’, as some of the apologists would have you believe, but the n–ger.” Supporters hailed Vardaman, who served as a Mississippi governor and U.S. senator, as the state’s “Great White Chief.”

The 1890 provision at issue is Section 241 of the Mississippi Constitution, which originally permanently disenfranchised people who committed the following crimes: bribery, burglary theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretense, perjury, forgery, embezzlement and bigamy. In their effort to only include crimes they believed Black people were most likely to commit, the white-supremacist drafters of the 1890 Constitution did not originally include murder and rape as disenfranchising crimes.

“If Section 241 had never been amended, the provision would violate the Equal Protection Clause,” the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals’ majority said in its ruling Wednesday. “… Critically, however, it has been amended.”

The State amended the Constitution in 1950, removing burglary as a disenfranchising crime. Later, in 1968, the 5th Circuit’s opinion says, the State made additional changes by voter referendum, including by adding “the ‘non-black’ crimes of ‘murder’ and ‘rape’ to the disenfranchising crimes in Section 241.”

“After careful consideration of the record and applicable precedents, we reconfirm that Section 241 in its current form does not violate the Equal Protection Clause,” the court said in an en banc opinion after a vote of all justices in the circuit. “Plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of showing that the current version of Section 241 was motivated by discriminatory intent. In addition, Mississippi has conclusively shown that any taint associated with Section 241 has been cured.”

But in the period when Mississippi made changes to Section 241, the state’s white leaders and white residents were engaged in an often violent and deadly campaign of mass resistance to federal civil rights laws and protections. Even in 1968, long after the Brown v. Board ruling, Mississippi still maintained segregated public schools until the U.S. Supreme Court issued a final order to desegregate in 1969.

‘An Opportunity to Right A 130-Year-Old Wrong’

In a dissent, Judge James E. Graves Jr. cited Vardaman’s admission about the purpose of the 1890 convention, noting that the so-called “Great White Chief” said the goal was to legislate “against the racial peculiarities of the Negro” and that “when that device fails, we will resort to something else.”

Graves, who is Black and a native of Clinton, Miss., joined the 5th Circuit after former President Barack Obama appointed him in 2011.

“This is the intent behind the law the en banc court upholds today,” Graves wrote. “In 1890, Mississippi held a constitutional convention with the express aim of enshrining white supremacy. … Today the en banc majority upholds a provision enacted in 1890 that was expressly aimed at preventing Black Mississippians from voting.

“And it does so by concluding that a virtually all-white electorate and legislature, otherwise engaged in massive and violent resistance to the Civil Rights Movement, ‘cleaned’ that provision in 1968. Handed an opportunity to right a 130-year-old wrong, the majority instead upholds it.”

Graves cited U.S. Sen. James Z. George, who said in 1890 that “the plan” behind the 1890 Constitution was “to invest permanently the powers of government in the hands of the people who ought to have them—the white people.” George is one of two Mississippians that the State honors with a statue at the U.S. Capitol; the other is Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

“Of course, all of the 1890 Convention’s 134 delegates were white Democrats, save just one African American Republican,” Graves wrote. “A white Republican named Marsh Cook had campaigned for a seat vowing to protect the rights of Black Freedmen. But a few weeks before the convention, his bullet-riddled corpse was found on a rural road in Jasper County.”

The judge noted that vestiges of the Confederacy remain, pointing out that Mississippi refused to change its Confederate-themed 1894 State Flag until 2020, following “insurmountable pressure” amid a national movement against structural racism.

“Even after this monumental step, in which Mississippi was forced to reckon with its past, more than vestiges of that past remain,” Graves wrote. “Since then, year after year without fail, the State recognizes April as Confederate Heritage Month. Mississippi is the only state to devote an entire month towards the Confederacy—whose position was ‘thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.’ And every January, on the day the rest of the nation celebrates the life of Dr. King, Mississippi celebrates the life and work of Robert E. Lee.”

‘A Haunting Reminder’

Near the end of the dissent, Judge Graves confessed that “recounting Mississippi’s history forces me to relive my experiences growing up in the Jim Crow era.”

“While I do not rely on those experiences in deciding this case, I would be less than candid if I did not admit that I recall them. Vividly,” he wrote. “So, I confess that I remember in 1963 a cross was burned on my grandmother’s lawn, two doors down from where I grew up.

“In December of 1969, I left my all-Black high school for Christmas break. It was after the Alexander decision where the Supreme Court declared Mississippi could no longer delay desegregation. As a result, I returned to my ‘desegregated’ high school in January of 1970. I was disheartened. Many of the best Black teachers at my high school had been transferred to a predominantly white school, and many of the worst white teachers had been transferred to my school. Not a single white student enrolled at my school.”

In 1991, Democratic Gov. Ray Mabus appointed Graves to serve as a state trial judge, he said, acknowledging that it was “evidence of progress in the struggle for racial equality in Mississippi.”

“But in the courtroom where I sat, the bench was flanked on one side by the United States flag and on the other side by the Mississippi flag and its Confederate emblem,” he wrote. “My inclination was to ceremoniously remove it from the courtroom. But there were others who were working to change the flag. They assured me that change was imminent. They were wrong.

“Ten years later I was appointed to serve on the Mississippi Supreme Court. There, the 1894 flag flew above the court, flanked the bench, and nestled in my chambers. And ten years later, when I began my service on this court, there again was the ever-present reminder of Mississippi’s sordid history. It is a testament to the greatness of this country and state that I have been selected to serve in the judicial branch of government. But no matter where I went, the 1894 flag was already there—a haunting reminder that a wrong never righted touches us all.”

Graves ended the dissent by declaring that, when it comes to Mississippi’s felony disenfranchisement law, “Mississippians have simply not been given the chance to right the wrongs of its racist origins.”

“And this court, in failing to right its own wrongs, deprives Mississippians of this opportunity by upholding an unconstitutional law enacted for the purpose of discriminating against Black Mississippians on the basis of their race,” he wrote.

“I dissent.”

Judges Carl E. Stewart, James L. Dennis, Stephen A. Higginson and Gregg Costa joined Graves’ dissent; all were appointed by Democratic presidents. Stewart and Graves are the only Black justices on the 5th Circuit. Two George W. Bush appointees, Catharina Haynes and Jennifer Walker Elrod, also wrote separate dissents.

‘This Ruling Doubles Down On This Legacy’

The MCJ first filed the lawsuit in 2017 on behalf of two Black men: Roy Harness and Kamal Karriem. Harness, a military veteran, lost his right to vote after a 1986 forgery conviction “during a time of drug addiction,” MCJ says.

“He served his sentence, stopped using drugs, and, at the age of 62, earned a degree in social work from Jackson State” but still cannot vote, the statement said. Karriem is an ex-Columbus city councilman who lost his right to vote after an embezzlement conviction in 2005. He now serves as a pastor and operates a family restaurant.

“For far too long, we as a nation have willfully deprived Black people of their right to vote—with Mississippi frequently leading the way,” MCJ President Vangela M. Wade said in a statement today. “This ruling doubles down on this legacy. Access to democracy should not hinge on outdated laws designed to prevent people from voting based on the color of their skin.”

After this story published, the Council on American-Islamic Relations issued a statement condemning the ruling.

“It is indisputable that Mississippi enacted its felony disenfranchisement regime in 1890 in a pique of racism for the specific purpose of disenfranchising Black voters,” CAIR Trial Attorney Justin Sadowsky said. “It is also indisputable—as the bipartisan group of dissenters in the case all make clear—that, other than making technical revisions to the scope of felony disenfranchisement, Mississippi has never since considered whether its racist system of felony disenfranchisement should be maintained for non-racist or any other reason. The majority’s willingness to find that technical amendments to Mississippi’s felony disenfranchisement law cleaned it of its racist motivation is contrary to law, and we hope the Supreme Court will reverse this apologia for racism.”