There was a heaviness in my chest that I could not quite fathom for the longest time. It was a sort of broken-heartedness that

persisted in spite of illusory successes, in spite of clear confirmation that I should be at ease with myself. It wasn’t happiness that this weight obstructed; it was contentment, a sense of peace with who I have come to be.

It was you, my imposter syndrome. It is you.

I did not know who you were until recently, until I discovered the term coined to describe the feelings that had, for so long, acted as thorns piercing into my side. I did not even consider you to be a valid psychological diagnosis until I heard U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez discuss how you had begun to gnaw at her. It was a startling confession. She, an emerging youth icon, an embodiment of modern hopes and dreams, still hung her head in shame before you, as you spun your warped black magic.

You bewitched her. You bewitch me. And you continue to bewitch all of the souls who attempt to reckon with social structures predicated on ruthless prejudices against them, reminding them that they will never be enough.

Imposter Syndrome’s Soiled Feet

I remember the first time that I felt you creep into my heart with your soiled feet. It was my seventh-grade global studies class, my favorite. I felt myself smolder with robust passion as I discussed systemic inequality, global war and the ravages of poverty. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see my male classmates snickering at my remarks. My cheeks reddened with shame.

Was there something wrong with my words? Was I making sense?

Though I had not yet come to attach the label of “imposter” to my distorted cognition, those thoughts awakened a voice of self-doubt within me that I have since been unable to vanquish: you, imposter syndrome. You act as the helpless child within me that refuses to perish, looking at external individuals and institutions to validate your thoughts and pain and muddled emotions.

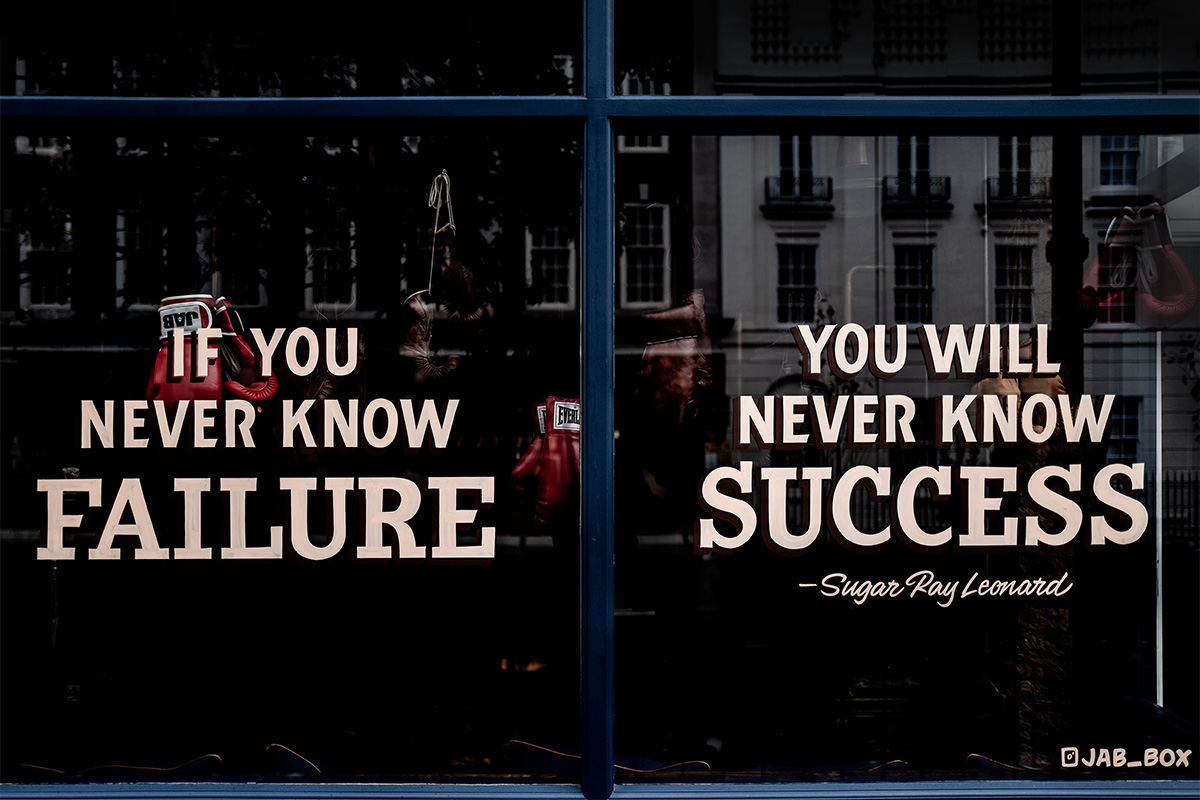

It is funny because I believed that I had outgrown you; that you were a diminished fragment of my past disassociated with my present confident, self-assured self. But now I realize that you are a double-acting devil.

You act first when we are most vulnerable, when our future truly appears to be muddled, and when our thoughts of self-doubt have credence because we have not yet discovered ourselves. Then you are an impediment that we come to outgrow as we develop a sense of confidence.

Some of us are fortunate to have our rendezvous with you only in that phase of our life. But these are the ones of us for whom success has not only a purpose, but is a prerogative.

For those of us who see success as an elusive green light—an alluring promise of the unrelenting American dream whose fulfillment we have dedicated our lives—you strike again after we have traversed the glowing bright waters, achieving the laurels we thought forever unattainable. We began to crumble as others fuel your deadly fire, dismissing our successes as a consequence of circumstances.

“You only got the promotion because they wanted a woman of color in an administrative position,” they say.

“Yes,” you, the imposter, says.

“Well, that explains it,” we say.

“You only got into your dream school because you wrote an essay about your struggles with your disability,” they say.

“Yes,” you say.

“Well, that explains it,” we say.

“You only got the research grant because your experiment turned out to be successful by chance,” they say.

“Yes,” you say.

“Well, that explains it,” we say.

You prevail because we humans have a self-effacing proclivity towards rationalizing the occurrences of our daily life.

Our world is incredibly unpredictable, and rationalizations lend some order to this indomitable chaos. Undertaking such a course of thought, we obtain an apt justification of our successes, but at a devastating cost to ourselves.

In an endeavor to seal the cracked gaps in our perspective of the world around us, we obliterate our own self-perception. We become broken, not because of any other external force, but because you overcome our consciousness.

Intelligent and Accomplished, Yet Personally Unfulfilled

In your classic act of deception, you make us feel that we languish alone in our misery, that only we cower before our unwavering thoughts. But the very fact that you are able to manipulate us into considering your whims is an emblem of our success.

One of America’s most beloved poets, whose beautiful mastery of colloquial language continues to enchant us today, Maya Angelou, struggled with imposter syndrome. Despite being the author of 11 books and the winner of several prestigious book awards, Angelou was sickened by the thought that, “I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.” She could not acquiesce to the fact that her accomplishments were hard-earned.

Similarly, the most genius man to have ever lived, none other than Albert Einstein himself, was convinced that his enormous achievements had no value, describing himself as an “involuntary swindler.”

Even though accomplishments of the magnitude Angelou and Einstein achieved are rare, their feelings of worthlessness are extremely common.

In fact, their widespread nature, especially among accomplished young women, prompted psychologist Pauline Rose Clance to investigate this phenomenon amongst her undergraduate students. She noticed that her most outstanding students, in spite of their high academic performance, were personally unfulfilled because they all believed that they did not deserve their place in the university. Though Clance knew these feelings were baseless, she realized that they warranted credence; after all, she had felt the same way in graduate school.

Along with her colleague Suzanne Imes, Clance established the presence of this phenomenon across gender, race, age and a range of occupations. However, Clance noted that the presence of imposter syndrome was more pervasive among marginalized social groups, such as women and those with disabilities.

Thus, you tend to dominate our consciousness because people who are highly skilled tend to believe that others are just as talented. We are goaded into a painful illusion of relative success, wherein our success is only valuable as it is measured against somebody else’s triumphs. Our accomplishments find their underpinning to be others’ failures.

And when our success exists only on the basis of someone else’s failure, there begins to appear nobody more failed than us. If you have such an incredible potency to destroy our self-image, is there anything we can do to escape your poisonous grasp?

First, we must realize that we are not alone in our moments of despondency; instead, a lineage of highly illustrious people accompany us.

Next, we must understand that you are a direct consequence of debauched thoughts. While we have little control over our external circumstances, we wield great power over our cognitive processes. Recognizing our doubtful thoughts and converting them into positive impulses can help to diminish your harmful psychological consequences.

Finally, we must surround ourselves with a circle of friends who do not mock our accomplishments or sully our successes with their envy. Instead, we must inundate ourselves with people who celebrate our victories as we do our own, and who are not threatened by the thought of our outshining them, but challenged by it.

Because you, imposter syndrome, are a lie. You rejoice in falsehood and cower before the truth.

Because the truth is, I am enough.

She is enough.

They are enough.

And you, imposter syndrome, are a psychological affliction of those who are indeed enough.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.