Twenty-five inmates at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, a city in Rankin County, will soon be able to work, earn at least the minimum wage and save half their earnings if Gov. Tate Reeves’ signs a Senate bill the Mississippi Legislature passed last month.

Senate Bill 2437, which Senate Corrections Chairman Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, sponsored, will give nonviolent offenders a pre-arranged job after they have completed their time in prison, the senator told the Mississippi Free Press in an April 13, 2022, phone interview.

“The best that we can do is to not wait for the people to get out for them to try and find work, but to try to rehabilitate them as much as we can while they’re incarcerated and help them find work. So when they get out, that’s one huddle that they don’t have to overcome in trying to find employment,” Barnett said.

Former Columbus, Miss., Councilman Kamal Karriem shared last October at an online event about his difficulty obtaining employment after spending two years incarcerated on charges of embezzlement when he was much younger. “Because of my (criminal history) and stigma that society has put on me, I can’t even get a job frying chicken,” he said, disclosing that he submitted 43 job applications with no success after coming out of prison.

Criminal History Hinders Employment

Researchers published findings in the Science Advances Journal in February 2022 on the impact having a criminal history places on finding employment. State University of New York at Albany School of Criminal Justice Professor Shawn Bushway and four others found that unemployed men between ages 30 and 38 had substantial involvement with the criminal-justice system. Bushway is also a senior policy researcher with the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit think tank.

Our new study estimates that more than half of unemployed men at age 35 have a criminal history of arrest—a stigma that poses a barrier to them participating in America's labor force. https://t.co/OIyPbIiA5t pic.twitter.com/4ckADDXjUJ

— RAND Corporation (@RANDCorporation) February 19, 2022

In a RAND Corporation press release last month, Bushway explained that while most government programs focus on providing the unemployed with new skills to get them into the workforce, they don’t do enough to address the hurdle of criminal history.

“The unemployment system almost never looks at the role that criminal history plays in keeping people out of the workforce,” he said. “Most employers believe that most people with criminal histories will commit offenses again.”

“But that is not the case. And the risk of reoffending drops dramatically as people spend more time free in the community without a new conviction. Employers need to adopt a more-nuanced approach to the issue,” Bushway added.

They ‘Want to Get Out and Go to Work’

Barnett said that even before the Mississippi Legislature passed SB 2437, which had the full support of every member, businesses had contacted him because they could not find employees and were excited to be able to use inmate labor.

“There are employers out there that are looking for people to hire,” he said. “And there were people that have been incarcerated that want to get out and go to work.”

The RAND Corporation said that a reason many businesses have understaffing issues is that a large number of employers do not want to hire people who have been convicted of crimes.

“Employers need to understand that one big reason they cannot find the workers they need is (that) too often they exclude those who have had involvement with the criminal justice system,” RAND Senior Policy Researcher Shawn Bushway, who led the study, said in the press release. “Employers need to reconsider their protocols about how to respond when applicants have some type of criminal history.”

In Senate Bill 2437, Sen. Barnett said prison authorities will take 10% of the inmates’ income as administrative costs, including transporting inmates to and from work. Twenty-five percent of the inmate’s wages will be used to pay fines and restitution, and the inmate may spend 15% while saving 50%, which they will have access to after release.

Alicia N. Netterville, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi, said those with whom she spoke who were previously or are currently incarcerated do not mind the 10% administrative charge.

“They know that the program has to be paid for; they know that transportation has to be paid for; and they would rather be out working rather than sitting in the cell all day,” she said. “But they don’t want 80% of their income to be taken—they don’t want to work and then leave prison worse off than when they went in.”

From the statute that Mississippi Prison Industries operates under, the organization controls up to 80% of the inmates’ earnings, which goes toward taxes, room and board, supporting their families and contributing to the Crime Victims’ Compensation Fund.

While Senate Bill 2437 requires the payment of prevailing wages for inmates and for workers to make no less than the federal minimum wage of $7.25, the practice of the Mississippi Prison Industries provides no such protection. To be eligible for the work-release program at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility, an inmate must have at least two years remaining in their term and not be sentenced as a sex offender.

Barnett explained that the plan is for a two-year pilot program with a possible extension to other Mississippi Department of Corrections facilities. “Since I’ve been the chairman of corrections, my whole agenda has been to not only correct the behavior that caused the individual to be incarcerated, but to also help the people get out so that they don’t come back and continue to be a burden on the taxpayers,” the senator said. “We want them to be taxpayers, not burdens on the taxpayers.”

Barneett said those who participate in the work-release program can continue working on the job after release, and if they want to go somewhere else, they will have that work experience on their resumes.

House Bill: No Less Than the Minimum Wage

The requirement in SB 2437 that employers pay the prevailing wages for a job and not less than the federal minimum wage is also one of the many provisions in 2021 Bill 747 that Mississippi Rep. Gene Newman, R-Pearl, sponsored. In 2021, HB 747 gave the Rankin County sheriff the power to start a pilot work-release program.

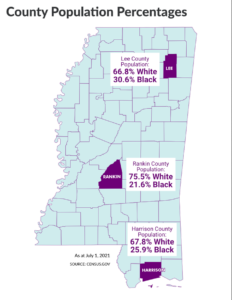

Gov. Tate Reeves, a native of Florence in Rankin County, announced on social media on April 11, 2022, that he had signed HB 586, which Rep. Newman also sponsored. The bill extends the program until 2024 and adds Harrison and Lee counties. More than 65% of the population in Rankin, Harrison and Lee counties are white. None of the more-than-20 majority-Black counties in the state are part of the program.

“Dignified work has the potential to offer new beginnings, change lives, and reduce recidivism rates,” the governor wrote Monday. “I was proud to sign House Bill 586, which expands the existing work-release pilot program to Lee and Harrison Counties and gives certain nonviolent inmates additional opportunities to work in their communities and better prepare to rejoin society.”

“We’ve seen tremendous success in this program in Rankin County, and I look forward to seeing the continued impact that this program will have on our people and our state!” Reeves concluded.

Barnett explained that because such programs provide for the payment of prevailing wages to inmates, it’s not going to drive employment away from other groups in society.

“So it’s not like they are going to pay them less than what they were paying anyone else; they would have to pay them the same as they were paying anyone else,” he said.