When James Marquis Jr. was about 5 or 6 years old, he got his first model train set. It was a common request from young boys then, many of whom were fascinated by actual trains as railroads were vital transportation and economic-development forces in towns across Mississippi.

“I’ve kept it safe to this very day because I’ve always loved trains. I’ve always lived within walking distance of a railroad and saw them day and night,” Marquis, now curator of the Martin and Sue King Railroad Museum in Cleveland, Miss., says. Even now I can sit in my living room and watch the active rail line that runs up through Marks when I’m off work.”

Across the United States, industry long attracted the construction of railroads to facilitate transportation of materials between heavily developing areas. In Mississippi, a number of cities owe their very existence to railways, with towns growing up around outposts that originally began only to serve the trains and rail workers, leading to the rail lines attracting industry rather than the other way around. And other towns shrunk or vanished when railroads left.

Today, rail enthusiasts across the state work to preserve and spread the history of Mississippi’s railways at museums dedicated to trains of all shapes and sizes, from preserved historical cars to intricately detailed models depicting life in rail towns both old and new. Through their efforts, they also hope to spread their fervor for trains and the railroad system to new generations.

“I found out about this museum through a group of rail-loving friends who told me about it when construction was just starting, and I knew I wanted to be involved,” Marquis continues. “Today, I feel like a lot of people under 30 might never have even ridden a passenger train before or may not recognize some of the memorabilia we keep preserved and might need it explained, and that’s what we’re here to do.”

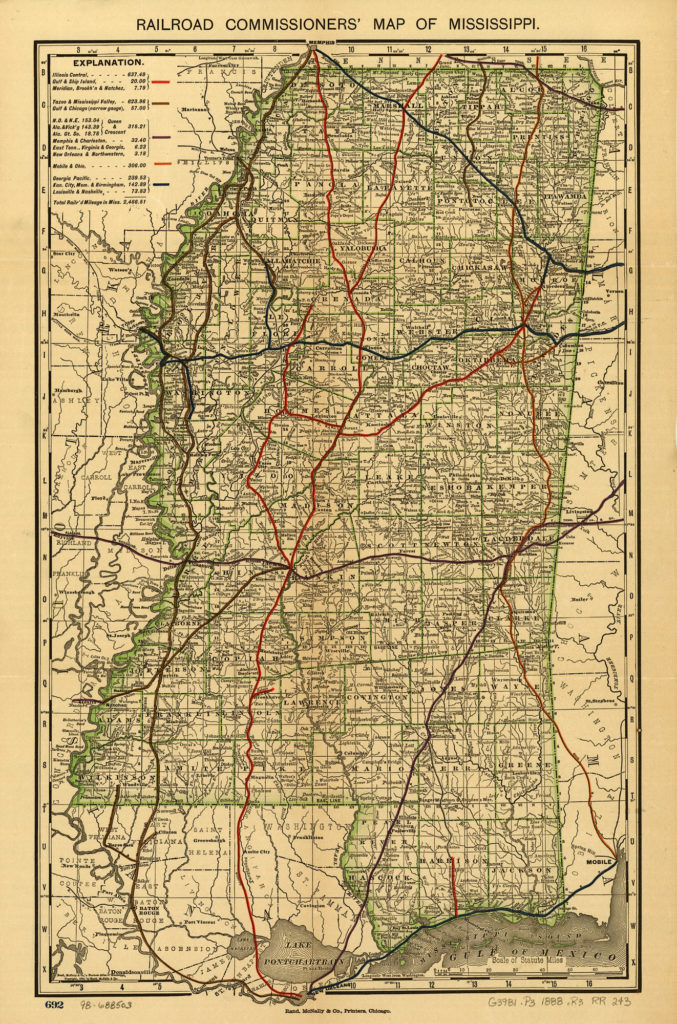

Mississippi’s Early Rail History

The earliest efforts to construct railroads in Mississippi date back to roughly the early 1800s, during a time when much of the Mississippi Delta was still swampland filled with hardwood and cypress trees. Lumber companies in northern states saw opportunities for logging and shipping there, Marquis says.

Before rail lines came, loggers would cut down trees and float them down rivers to sawmills for processing and transport. After loggers had removed enough trees and stumps and drained water from swampy areas, farming became possible. From there focus eventually shifted from logs and raw materials to one of Mississippi’s most famous historical exports: cotton.

One of the earliest rail lines in Mississippi was the West Feliciana Railroad, which began after the Louisiana Legislature chartered it on March 25, 1831. The Mississippi Legislature eventually authorized the construction itself in December 1833. The line, which officially began construction on Dec. 22, 1834, became one of the first interstate railroads in America, running roughly 26 miles from the port of Bayou Sara, La., to Woodville, Miss.

By the 1850s, the state had roughly 75 miles of track, including the Mississippi Central Railroad, which the state Legislature chartered in 1852. The line ran from Canton, Miss., to Grand Junction, Tenn., and passed through Grenada, Water Valley, Oxford and Holly Springs along the way. Passenger service also began for many Mississippi rail lines during the 1850s.

Another significant line was the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad, which was part of the Illinois Central Railroad system and ran from Memphis to New Orleans from 1882 until 1946.

Train Industry Builds Cities

Cleveland, home of the Martin and Sue King Railroad Museum, was one of several cities in Mississippi that sprang from the need to expand rail services in the state. The site of what is now the city housed part of the former Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railroad, which the Commonwealth of Kentucky chartered in 1850 and ran from New Orleans to St. Louis, Mo.

Construction on the settlement began in 1869, though the town went through many names such as Fontaine, Coleman’s Station and Sims before being officially chartered as the village of Cleveland on March 25, 1886. Former U.S. President Grover Cleveland, first elected in 1885, is the city’s namesake.

“In those days they had trains running from Memphis to Vicksburg carrying commodities like cotton and cattle feed,” Marquis says. “Over time they started putting buildings closer to the tracks where all the work was being done, and then as more workers came in they started building places to sleep. After that came a general store for commodities, and then a depot, and Cleveland kept growing from there. Those railways kept running through Cleveland until around 20 years ago, sometime around the beginning of the 2000s.”

Parallel rail routes running roughly 25 miles to the east eventually led to the Cleveland line generating less revenue for the railway companies, causing figureheads of the industry to elect to abandon the railway running through the city and begin pulling up tracks. Even though much of the old rail lines are gone, portions of some of them such as the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railroad still remain, and residents of Cleveland have worked to preserve the town’s rail history.

The Martin and Sue King Railroad Museum, established in 2009, takes its name from the late Martin King Jr. and his wife, Virginia Sue Thweatt King. King served as mayor of Cleveland for roughly 30 years, and during his tenure he loved to keep model trains on desks in his office, Marquis says. After he passed away in 2012, the museum took on the Kings’ names to honor them and their love of the town’s rail history.

“We have all kinds of railroad tools and memorabilia here, from luggage wagons and potbelly stoves to cotton sacks, lanterns for signaling, headlights from locomotives and even signage from old towns,” Marquis says.

“We also maintain one of the largest model train tracks in the state, with 1:48 scale models representing about 15 different kinds of train models from the 1950s to the 1970s. We have about 1,000 feet of track in the museum arranged in two ovals, with trains anywhere from 3 to 15 cars long that we operate via digital remote control. The period of time these old tracks represent, back when the rails here were busy during their heyday, is important to us here.”

The Martin and Sue King Railroad Museum is open Tuesday through Friday from 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. For more information, call 662-843-3377 or visit clevelandtrainmusuem.com.

McComb City Railroad Depot Museum

Mississippi’s rail lines have given rise to other towns in the state as well. McComb, far to the south of Cleveland, shares similar origins. The town got its start in 1872 when former Union Army Col. Henry Simpson McComb gained the rights to the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad through a special charter.

“That railroad was connected to the Illinois Central Railroad, which was one of the main lines of middle America running from Chicago to New Orleans,” Ralph Price, executive director of the McComb City Railroad Depot Museum, says.

“After getting the railroad rights, McComb decided to move the railroad’s maintenance shops from New Orleans to a new location roughly 100 miles to the north of the city to try and keep his workers away from what he saw as the vices of the day, like saloons. He might not have been necessarily successful in that regard, I think, but it did lead to a rather interesting scenario of an industry creating a city rather than a city attracting industry to it.”

The shops for which McComb directed construction began as a 64-acre complex of repair shops for train cars, axles, brakes and engines, Price says. From there, a carpentry shop and a metalworking foundry followed, with the site eventually employing more than 1,000 people. The complex that the City of McComb grew out of remained operational until two large sets of layoffs in 1982 and 1985. Shortly afterward, the rail company that owned the complex started tearing some of the old buildings down to avoid paying property taxes.

McComb City Railroad Depot Museum co-founder Edwin Etheridge, who had served as the depot’s superintendent for more than 25 years before its closing, joined forces with Winnie Len Howell to begin salvaging and collecting as many artifacts as possible from the depot, including steam engine bells, lamps, coal lanterns and more. Etheridge passed away in 2010.

The McComb City Railroad Depot Museum eventually opened in 2003 on the south side of the old rail depot. In 2014, the museum expanded to occupy all of the former complex aside from an old Amtrak complex that two organizations, the Pike County Chamber of Commerce and the Economic Development Foundation, still owned. When the two organizations relocated to Main Street and Southwest Community College, respectively, the museum gained 2,000 square feet of new space.

Among the larger artifacts that the museum maintains are actual train cars that formerly ran the tracks, many with a history of their own. One of the more unusual cars is an aluminum refrigeration car that was constructed in McComb that is now the last of its kind, Price says.

“Back before refrigerators, rail workers would transport cars loaded with vegetables and other perishables shipped in from as far as Central America and would stop in McComb to bring them to what was one of the largest ice-making plants in the world,” Price says. “Workers could ice 50 cars in under an hour using large blocks of ice underneath metal crates.”

“The one we have was built in 1947, but the aluminum used in its construction was deemed too light to use, so it was set to be decommissioned,” Price continues. “Edwin (Etheridge) actually went out of his way to save it because it was one of the only ones of its kind built in McComb. He hid it from management by moving it around to different towns so that they wouldn’t find it.”

Other unique train cars at the museum include an executive office car built in 1883; a 1914 railway postal car that served as a post office on wheels along the Illinois Central rail line; a 1965 caboose that was one of the largest of its kind; and a 1956 wrecker and derrick car with an attached crane formerly used to clear derailed cars.

On May 30, 2021, an arsonist destroyed much of the old depot, but the museum is working to repair and re-roof the buildings that remained standing and recreate and renovate their interiors. Staff are keeping artifacts stored in a separate, climate-controlled depot while construction is ongoing.

“The fire was a tragedy that none of us hoped for, but it has given us a chance to enhance the museum with new technology and interactive upgrades like an engine simulator,” Price says. “We’re proud of what we’ve created here and we want to be able to make it even better.”

The McComb Railroad Museum is open Monday through Saturday from noon to 4 p.m. For more information, call 601-684-6487 or visit mcrrmuseum.com.

‘Connecting’ Through Trains

Meridian, in the eastern part of Mississippi, is another city that owes its existence to railroads, including its initial construction and a reconstruction after the Civil War.

The city’s origins date back to 1831, following the Choctaw Indians that lived in the area signing the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Virginia native Richard McLemore was among the first settlers in the area and began building up what would become Meridian around a rail depot, much like Henry Simpson McComb would do after him. McLemore offered free land to settlers to draw more people to the area, which led to expanded railways.

“By the 1860s, when an intersection for the

Mobile and Ohio Railroad and the Southern Railway of Mississippi was completed to link the railways together, Meridian had grown from about 15 pioneer families into one of the largest cities in the state, and one of the only ones to have two round houses during the age of steam trains,” Lucy Dormont, president of the Meridian Rails Historical Society and acting executive director the Meridian Railroad Museum, says.

“Meridian’s round houses had (at least) 16 stalls to store and move different train cars onto the multiple lines going through the area. Back then Meridian was a junction for at least five different rail lines, with even more planned before the outbreak of the Civil War,” she added. “During the war the town housed a Confederate arsenal, a military hospital, a prisoner of war stockade and a headquarters for military officials.”

The final days of the Civil War nearly spelled the end of Meridian, as Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman captured the city during February 1864 and ordered the city burned down and rail lines destroyed to disrupt Confederate operations.

After the war was over, however, rail workers gathered together to rebuild Meridian and its rail lines and accomplished the task in only 26 working days, ushering in what would come to be called the city’s “Golden Age” from roughly 1890 to 1930, Dormont explains, even as the period coinciding with Jim Crow was not very golden for Black Meridian residents. During that time, Meridian became Mississippi’s largest city of the era and a leader in manufacturing for the state. Today, with an estimated population of 41,148 as of 2018, Meridian is now the seventh-largest city in Mississippi.

“Meridian having all this deep railway history and no active museum for it when my family first moved here from (Virginia Beach in 2017) didn’t seem right, and I started looking into it,” Dormont says. “My sons, Connor and Owen, both love trains and would hang out here all day if I let them. Building model-train sets together has been a great way of connecting for us.”

Dormont’s interest in setting up what is now her museum began after a friend asked her to help design a Meridian-themed logo for her real-estate business, which led to Dormont researching the city’s history. She discovered that there had been a Meridian Rail Museum in the city until about 2016, when its director, Mick Nassbaum, passed away.

A man named Jack Stack had deeded the building that houses the museum, which was a former railway express agency building, to the City of Meridian in 1991 specifically for the construction of a rail museum, Dormont says, with the building to be used as such for at least 50 years as a requirement of the lease. The City had been planning to instead use the building to house a museum dedicated to musician Jimmie Rogers, who had also done rail work during his lifetime.

“When I found out about this and what the building was deeded for, I decided to step in,” Dormont says. “I went to the city council and told them all I had found and volunteered to head up a new rail museum, and the City donated the building to our organization. The building had been sitting abandoned for five years, but we got it up and running by November 2021 in time for a big Christmas turnout. This project was important to me because I wanted this museum to be able to tell the stories of thousands of individuals over generations instead of just one.”

The museum, whose structure is part of the original rail depot that Meridian grew around, is a registered historic landmark for the state of Mississippi. Among the museum’s artifacts are a Sherman’s “Bow Tie,” a piece of steel railroad track that Union soldiers heated and twisted around trees to prevent Confederate troops from fixing the rail lines, as well as a track inspector bike, a training stoker and more. The Meridian Rail Historical Society is in the process of acquiring and cosmetically restoring the Meridian and Bigbee #116, a 2-8-0 consolidation type locomotive that Baldwin Locomotive Works built in 1917 for the Susquehanna and New York Railroad. The 116 also has the only known replica of the whistle from the engine of famous railroader Casey Jones.

The museum also houses “Miss Alva,” a coach car used for the 1966 Sydney Pollack film “This Property is Condemned,” named for Alva Star, the character that the film’s star Natalie Wood played. The renovated coach keeps the movie playing on loop within a lounge that recreates the movie’s set.

“Having pieces of history like these is special to us, and I feel strongly about giving the rail workers that build Meridian a voice and keeping their stories alive,” Dormont says. “Many would say that rail culture has faded or changed, but I think that now a new generation has risen up that cares about preserving this history.”

Each November, during Whistlestop weekend, the Meridian Rails Historical Society hosts Rail Fest, wherein enthusiasts from Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida and Alabama gather to celebrate their hobby. The event features 40,000 square feet of model train displays as well as vendors selling various train memorabilia. In conjunction with Rail Fest, the Mississippi Industrial Heritage Museum organizes Soule Live Steam Fest in the same area.

The Meridian Railroad Museum is open on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. For more information, call 601-693-2111, email info@meridianrails.org, visit meridianrails.org or find the Meridian Rails Historical Society on social media.

Mississippi Coast Model Railroad Museum

For those with a love of trains on a smaller scale, the Mississippi Coast Model Railroad Museum in Gulfport, Miss., has everything an enthusiast could hope to find. The museum runs more than 100 model trains continuously, which visitors can activate with the press of a button.

The facility contains more than 7,000 square feet of buildings and birthday party rooms and is expanding into 50,000 feet to include more tracks for the models, including four large-scale outdoor tracks and “garden railroads” landscaped with live plants. The museum also contains a LEGO train set with more than 2 million pieces that includes representations of major world landmarks such as the Statue of Liberty and the Taj Mahal.

“Members here build our own models and maintain the trains ourselves,” Richard Mueller, president of Mississippi Coast Model Railroad Club, says. “People learn to love model-building in many different ways, whether its Lincoln Logs or Erector Sets, but with model trains it’s about more than just trains running on tracks. It’s about creating scenery and vignettes, dioramas.”

The Mississippi Coast Model Railroad Club got its start at the Singing River Mall in Gautier, Miss., roughly 30 years ago, Mueller says. Members would gather at the mall with two-sectioned tables and put them together in an oval formation to run their trains on, with the arrangement designed so that more tables could be added over time. The group operated out of the mall for more than 20 years before it closed, after which the organization spent a year in Ocean Springs, Miss., before settling in Gulfport and opening what is now the museum.

Model trains are divided up by scales, which refers to the size ratio of the model compared to the size of the real train it represents. The smallest is Z scale, which is a 1:220 model, meaning it is 220-times smaller than life-sized objects. Z scale sets are often small enough to carry and display inside a briefcase.

The next size up is N scale at a 1:160 ratio. HO scale, at 1:87.1. ratio, is one of the most common commercially available model sizes in the United States and Canada. O scale, at a 1:48 ratio, was one of the original scales that famous model train manufacturers such as Lionel used. Lionel’s American Flyer brand is also one of the only remaining commercial S-scale models available, which comes in a 1:64 ratio. Larger models fall under the broader category of G scale, which ranges anywhere from 1:32 to 1:12.

“I got my first model train set for Christmas when I was 10 years old, and it remains on display in the museum to this day,” Mueller says. “In those days the models were often heavier than those of today with lots of metal, and you had to be careful because you could make a spark if you didn’t put the train on the electric tracks right. I remember putting it together and running it around the Christmas tree. When I got older I started doing odd jobs and would regularly go to the hobby shop to buy more cars and tracks, and I built my own tables at home so I could start putting together larger and larger sets.”

The Mississippi Coast Model Railroad Museum is open Wednesday through Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. For more information, call 228-284-5731 or visit mcmrcm.org.

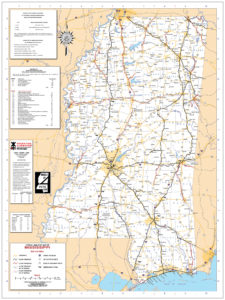

Other Areas Ripe with Railroad History

Mississippi rail enthusiasts have far more options available to them across the state. The Old Depot Museum (1010 Levee St., Vicksburg) in Vicksburg features model layouts of scenes from Mississippi, including the Siege of Vicksburg during the Civil War, in O-scale, HO-scale and N-scale layouts. The museum also contains models of historical buildings such as the Windsor Mansion in Bruinsburg and the Old Yazoo and Mississippi Railroad Depot, as well as a section dedicated to models of boats from the state’s maritime military history.

The Crossroads Museum (221 N. Fillmore St., Corinth) in Corinth is located adjacent to the original railroad tracks first established in the area in 1854. The museum’s installations allow visitors conductor-level views of passing trains from a second-level viewing platform located just above a historic fire truck display, as well as artifacts from the city’s industrial period. The museum also houses the Margaret Greene Rogers Library, a vintage train caboose and a Civil War cannon used during the Battle of Shiloh.

The Rails and Trails Museum (100 Truman St., Booneville) in Booneville contains three major exhibits focused on the history of the Bear Lake valley. The railroad exhibit features items such as a cuspidor, an order hoop, a time schedule board, railroad tools and more. The Daughters of the Utah Pioneer exhibit contains items that pioneers brought into the valley by wagon. The Bear Lake County Historical Society exhibit contains more recently donated items that reflect the early history of Montpelier and the Bear Lake valley.

The Merci Train (648-698 E. Pearl St., Jackson) in downtown Jackson dates back to 1947, when Washington Post columnist Drew Pearson launched a grassroots effort to help France and Italy recover in the aftermath of World War II. The effort brought in $40 million worth of supplies from across the United States that filled more than 700 railroad cars, which became known as the American Friendship Train.

In response, the French later sent the Merci Train, featuring cars decorated with placards of the coats of arms of all of the provinces of France. Each of the then 48 U.S. states received a car, as well as an additional one to be shared between Washington, D.C., and Hawaii. Mississippi’s boxcar arrived in Jackson on Feb. 12, 1949. The Mississippi Department of Archives and History received 40 objects from the Merci Train that are still in the permanent collection.

The GM&O Depot (618 E. Pearl St.) in Jackson, which the New Orleans Great Northern Railroad originally constructed in 1927, served the Gulf, Mobile and Northern Railroad, as well as the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad, until its discontinuation in 1954. The state of Mississippi later acquired and rehabilitated the building in 1982 for offices of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

The Illinois Central Railroad built the Alabama and Vicksburg Railroad Depot (200 S. Main St., Newton) in Newton in 1904 and oversaw its operation thereafter. Also known as the Newton Railroad Depot, the site joined the National Register of Historic Places’ list of important landmarks in 1990.

Learn even more about Mississippi’s railroad history here.