Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of race violence.

Willie Baker, an 18-year-old Black man, was en route to the jail in Monroe County, Miss., on March 7, 1922, when a violent white mob overpowered the constable who was transporting him. The ravenous white residents carried him to a chinaberry tree, stringing him up by the neck on one of its limbs until he was dead.

When the nearby town newspaper, The Aberdeen Weekly, reported his death two days later, they did so under the heading, “A Hellish Crime”—but not in reference to his brutal murder.

“The most heinous crime of which fiends are guilty occurred about 10 miles north of Aberdeen Monday, when Willie Baker, an 18 year old negro youth, criminally assaulted the six year old daughter of one of the most reputable white families of the county,” the newspaper reported. “… The sheriff was notified of the assault and started deputies to the scene, but before they could get hold of the prisoner the unwritten law of quick and certain death had been meted out to the fiend.”

The paper claimed it was “the second case where negroes have criminally assaulted white girl children in Monroe County” and that the other alleged perpetrator had also died by “the rope route,” or lynching.

“As long as such crimes transpire in this country—north, south, east or west, the fiend will die, and a mob will execute the penalty,” The Aberdeen Weekly declared.

An alleged, but unproved, assault on a white woman or girl was a common excuse for mob lynchings through most of Mississippi’s history. In fact, lynchings and mob racial violence were often used to scare Mississippians who believed in Black equality, good education and the opportunity to work for a decent work and accrue wealth, or to punish a Black citizens who did not fall in line and bow to white supremacy.

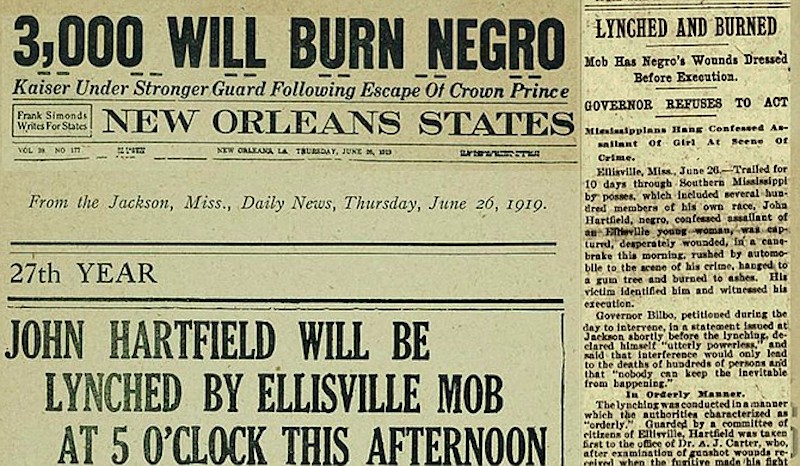

From Reconstruction in the late 1800s until the mid-20th century, Mississippi boasted the most lynchings in the nation—with Black men and boys like Willie Baker often the victims of extrajudicial, white vigilante mobs that local newspapers used as fodder for entertainment and to sell papers, even announcing planned lynchings in advance, which in turn helped swell the lynch mobs and the crowds there to watch and cheer them on. That included Mississippi’s largest newspapers like the Jackson Daily News, and newspapers across the South that picked up each other’s lynching stories and accouncements.

Yesterday evening, exactly 100 years to the day of Baker’s murder, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a federal antilynching law, making lynching a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison. The House of Representatives passed it last month.

‘Confronting The Reality of Racist Violence’

The bill, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, is named for the 14-year-old Black child whose brutal murder in Money, Miss., in 1955 propelled the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

“Today, the House took an important step to advance the cause of justice by finally designating lynching as a hate crime under federal law,” U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in a statement after the House passed the bill on Feb. 28. She added that “we are confronting the reality of racist violence and helping to build a safer future for all of our children.”

“Nearly seven decades later, the brutal murder of Emmett Till is forever seared into our collective memory. Sadly, hateful attacks are not yet a relic of the past: from the scourge of police violence to assaults on houses of worship.”

U.S. House Rep. Bobby Rush, an Illinois Democrat whose congressional district includes much of Chicago’s south side, sponsored the bill. Till, who lived in Chicago, was visiting family in Mississippi when he was lynched.

“Today, we correct this historic and abhorrent injustice,” Rush said in a statement yesterday. “Unanimous Senate passage of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act sends a clear and emphatic message that our nation will no longer ignore this shameful chapter of our history and that the full force of the U.S. federal government will always be brought to bear against those who commit this heinous act.

“I am glad to see this bill receive unanimous support in the Senate—and near-unanimous support in the House of Representatives—and look forward to President Biden signing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law very, very soon. At this moment, I am reminded of Dr. King’s famous words: ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.’”

The legislation now goes to the desk of President Joe Biden, who is expected to sign it into law.

‘You Will Open The Floodgates Of Hell’

The feat concludes more than 200 attempts to pass an antilynching law over across more than a century.

In 1938, U.S. Sen. Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi joined other southern Democrats in a filibuster against an antilynching bill, invoking his Christian faith as he argued against it and warning that doing so would “lead us all on to that day when miscegenation or intermarriage between the races will be universally accepted and practiced … and then our doom is sealed.”

“If you succeed in the passage of this bill, you will open the floodgates of hell in the South,” he said in a speech on the U.S. Senate floor in January 1938. “Raping, mobbing, lynching, race riots, and crime will be increased a thousandfold; and upon your garments and the garments of those who are responsible for the passage of this measure will be the blood of the raped and outraged daughters of Dixie, as well as the blood of the perpetrators of these crimes that the red-blooded Anglo-Saxon white southern men will not tolerate.”

Years earlier, as Mississippi’s governor in June 1919, Bilbo had said he was “utterly powerless” to stop a white mob in Ellisville, Miss., from lynching John Hartfield, a local Black man who had allegedly been in a consensual relationship with a white woman—though some claimed he had raped her.

“The State has no troops, and if the civil authorities at Ellisville are helpless, the States are equally so,” he said at the time. “Furthermore, excitement is at such a high pitch throughout South Mississippi that any armed attempt to interfere would doubtless result in the deaths of hundreds of persons. The negro has confessed, says he is ready to die, and nobody can keep the inevitable from happening.”

As Hartfield hanged and burned, the mob shot bullets into his body—parts of which they would later sell as souvenirs.

Last month, a statue of Gov. Bilbo that has stood in the Mississippi Capitol since the 1950s disappeared. Mississippi House Clerk Andrew Ketchings later said he had used his power to move the statue because of Bilbo’s white supremacist beliefs.

‘A Bitter Stain on America’

In 2005, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution “apologizing to the victims of lynching and the descendants of those victims for the failure of the Senate to enact antilynching legislation.” Neither of Mississippi’s U.S. senators at the time, Republicans Thad Cochran and Trent Lott, joined 89 other senators who signed onto the resolution as co-sponsors.

Yesterday, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act passed with the support of Mississippi’s two white Republican U.S. senators, Roger Wicker and Cindy Hyde-Smith, and no objections. During her first U.S. Senate campaign in 2018, Hyde-Smith sparked a national outcry when she praised a supporter by saying that, if he invited her “to a public hanging,” she “would be on the front row”—a remark many took as a reference to lynching.

In 1955, the same year Emmett Till died in Money, Miss., Black businessman and voting advocate Lamar Smith was one of multiple Black men killed by white men in Hyde-Smith’s home of Brookhaven, which has a long history of brutal lynchings, but no markers to date to acknowledge that history. Brookhaven was more recently the site where two white men allegedly chased and shot at D’Monterrio Gibson, a Black FedEx driver, while he was out delivering packages in January 2022.

“After more than 200 failed attempts to outlaw lynching, Congress is finally succeeding in taking the long-overdue action by passing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. Hallelujah,” U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said last night. “The first antilynching legislation was introduced a century ago, and after so long, the Senate has now finally addressed one of the most shameful elements of this nation’s past by making lynching a federal crime.

“That it took so long is a stain—a bitter stain—on America. … We look forward now to President Biden quickly signing this long-delayed bill into law.”

Donna Ladd contributed to this story.