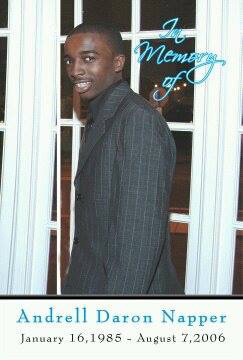

Andrell Daron Napper, 21, was visiting his cousin Rob in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a section of Brooklyn, N.Y., on Aug. 6, 2007. He was standing outside the building when Rob walked upstairs to get his phone. Gunfire suddenly rang out. Napper was not the target of the gunfire who, in turn, shot back at the original shooters—a 15-year-old and a 25-year-old. Andrell was caught in the middle of the barrage of bullets.

Oresa Napper-Williams’ oldest boy was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

After Rob called to tell her about the shooting, Andrell’s mother rushed to Woodhull Hospital where doctors were trying to save her son’s life. As she was waiting, a physician came out, but instead of focusing on the prognosis of her son, he began questioning Andrell’s involvement in his own murder.

“Hi, you’re the mother? So do you know what your son was doing over here?” the doctor asked Napper-Williams.

“No, I don’t,” she replied.

“Do you know who your son was visiting?”

She quickly stopped the doctor’s line of questioning and got straight to the point: She needed to know how her son was doing. What followed was the last thing she expected to hear from a medical professional.

“Oh, I’m sorry we couldn’t save him. We lost him,” he said before walking away.

Andrell’s mother remembers falling to the floor and wanting to hit the doctor, not because her son had died but because the physician lacked an ounce of empathy.

Her youngest son, Justin Napper, heard the news about his brother and took an hour-long train ride from Harlem to New Jersey, where she was staying temporarily. The siblings are a year and a half apart, and when the mother laid her eyes on her only remaining son, it hit her that she would never see her children walking together again.

As Justin moved toward her, Napper-Williams’ knees buckled, and she hit the ground. He walked over to her and urged her to get up, reminding her that Andrell, the son she had as a teenager she called Ronnie, wouldn’t want her acting in that way. ”I pulled up some strength, I wiped myself off, and I stood up. And I have been standing since those words,” she told the Mississippi Free Press.

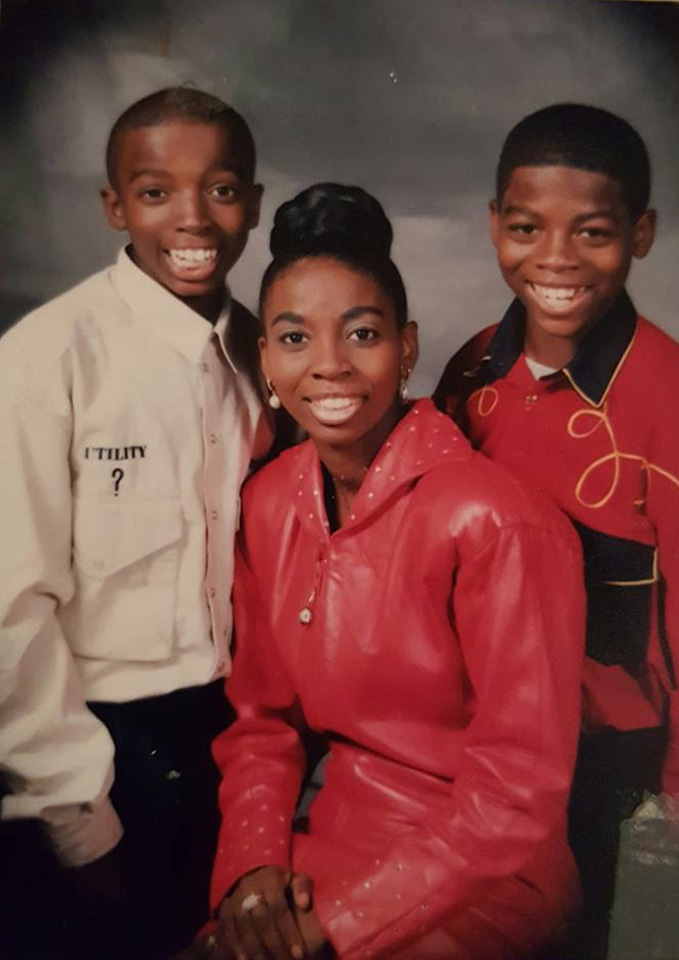

Napper-Williams, who is now happily married, was a single mother from Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn then who was raising her two sons alone. Despite being a single mother, she always had a good support system, and her community came out in droves to support her after the passing of her son.

“When I left that hospital, when they told me my son did not make it, I was put into a car and was not home for another month. I was just dating my husband now, but he went to my house and bagged up all my son’s stuff (and) left a few pieces just for me to have, so I wasn’t thrust right back into our apartment that just reeked of my son’s love,” she said.

The grieving mother didn’t pick out a casket and or pay for anything regarding funeral arrangements for services, which were held at her long-time East New York worship home, Love Fellowship Tabernacle Church, where she still sings in the choir. One of her mother’s friends, who does not drive, took a cab from her house in New York all the way to New Jersey with a large amount of food just as family and friends do in Mississippi. The funeral program had already been arranged, though she did write her son’s obituary.

“I’ll never forget things like that,” the mother added.

Often ‘No Empathy’ From Law Enforcement

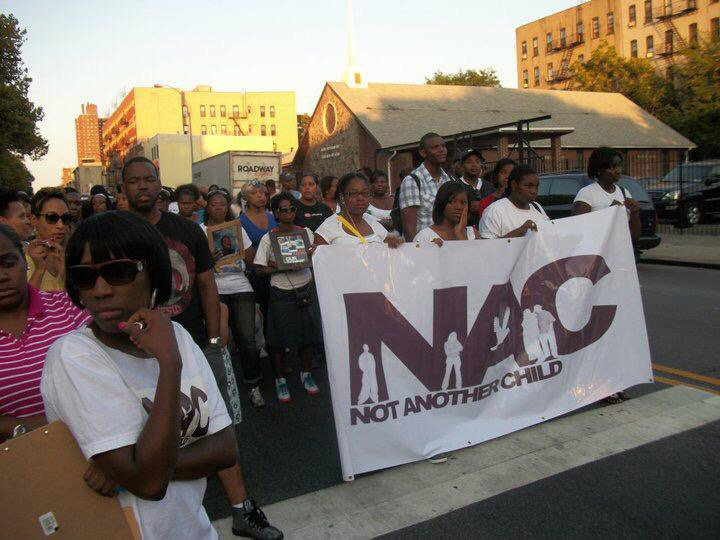

Today, Oresa Napper-Williams runs the nonprofit Not Another Child in New York City, through which she advocates for and works with families, like hers, who have lost children to gun violence so that the system respects and helps them through times of tragedy.

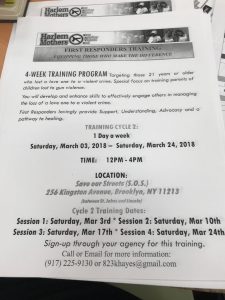

She also collaborates with the New York Police Department in anti-gun violence operations, appearing as the “Voice of Pain” in Operation Ceasefire call-ins. Ceasefire, when done as designed, is a carrot-and-stick series of gatherings of young people in gangs and at risk of committing violence with both threats of federal prison time and offers of preventative services to those who will accept them. Several years back, Hinds County and the Jackson Police Department attempted a Ceasefire program it dubbed “MACE,” but did not properly use the funds for services, instead using it only for police sweeps, which most violence experts consider the bottom of the chain for effectiveness in reducing harm and violence in a community.

Napper-Williams also collaborates with a deep network of credible messengers across New York City—such as the fledgling Strong Arms of JXN in Mississippi’s capital city since 2018—and surrounding areas who are using evidence-based, beyond-policing approaches to violence prevention.

The outspoken, fast-taking New York mother gets especially animated when law enforcement treats parents of violence victims poorly, including assumptions that their children got what was coming to them. That is particularly rampant toward Black mothers from New York City to Jackson.

“From working with parents, I know that it’s all depending on how the system sees you, the detectives and the precinct. The first call that I received from the precinct was: I’m just calling to tell you that I’m the detective on your son’s case, and I’ll let you know if he was involved in any way,” Napper-Williams recalls him telling her.

“You don’t have to let me know anything because I know my son wasn’t involved,” she told the detective and then hung up on him.

This lack of empathy, and assumption that a Black violence victim may have been guilty or “involved” in some way is a common response to family members, including in the capital city of Mississippi.

Police Ignoring Grieving Mississippi Families

Shaneika Green can recall well the lack of empathy she received from the Jackson Police Department when she has called to inquire about updates on her son Tramaine Green’s murder case. Tramaine, 26, was shot multiple times in South Jackson on July 17, 2020, and left on the side of the highway during the height of COVID-19 pandemic.

“I had to go down there and talk to the sergeant to find out,” Green told the Mississippi Free Press. “I had called one time, and I talked to him. I told him I’m trying to find out what’s going on with my son’s case. I haven’t heard anything, and he took my name and number (and) said he was going to call me back at a certain time. I ain’t hear from him.”

Green had to go to the police department herself to find out that the original detective on her son’s case had been changed. The mother of six is convinced by their actions that JPD officers are not concerned about the families who have lost loved ones and who do not want their cases to go cold, she said, echoing a refrain of many Black families in Jackson who lose children to violence.

From her experience with the Black-led JPD, Green believes their empathy is nonexistent.

“To me, it’s an act. They put on an act in front of us and no telling when we leave, they’re talking about (their) personal life, or (their) family or whatever and not trying to look into the case,” she added.

Green believes the least the police department can do is give families weekly updates to let them know they are working on the case, anything to assuage the family’s concerns. But it is closing in on two years since her son was murdered, and his killers are still walking free.

Some mothers from Napper-Williams’ healing circles have been conducting Zoom discussions with Brooklyn homicide detectives on their loved ones’ cases. All the mothers have to do is sign up, she said. But despite how good the idea sounds in theory, the organizer says these are still forced relationships between the victims and the department.

“It’s not pure, the relationship. (The Zoom calls) are not as often as they were because these cases go cold because they can’t find any witnesses. (But) I think it helps just to bring peace and kind of bring resolve to the situation of family members,” she said.

Napper-Williams said she doesn’t know if any of the calls actually helped crack any cases, and the times she has been on these calls, the detectives don’t have any updates. And there may be evidence, like video footage, but it doesn’t lead to any arrests.

The anti-violence leader who has sometimes collaborated with the NYPD said she believes this lack of empathy is embedded into the police system across the nation, especially toward Black families and victims.

“A lot of it comes with how they feel about the culture and about the people anyway. it’s a culture that they have because even with that, if you look, sometimes it’s not Caucasian cops that are acting like this. It’s the minority ones also,” Napper-Williams said.

Black Mothers Often Blamed or Ignored

Months prior to her son being killed, Napper-Williams had met Dorothy Johnson-Speight with Mothers in Charge, a violence prevention, education and intervention-based organization in Philadelphia, Pa. Johnson-Speight is a licensed therapist who lost her son Khaaliq Jabbar Johnson to gun violence in 2001 over a parking-space dispute. She then banded with other grieving families in Philly to start the nonprofit, which advocates for children’s and family rights around violence.

Napper-Williams took Johnson-Speight’s number then, though at the time she didn’t think it would be useful because it did not relate to her. She could not imagine a world in which she would soon lose a son to gun violence. But as a bullet struck her son down that August day in 2007, she was joined with a large sorority of mothers, sisters, wives and daughters who lose loved ones to the epidemic that preys, especially, on Black men in America. They are also women often blamed or ignored much as Shaneika Williams and other mothers experience in Jackson.

The Giffords Law Center reports that gun violence has a disproportionate impact on underserved communities of color in the country. And Black men make up 52% of gun-homicide victims in the United States, despite making up less than 7% of the population.

Johnson-Speight quickly called Napper-Williams after her son’s passing, and she would later on become the grieving mother’s mentor. Her support over time helped Napper-Williams navigate her new reality.

Following Andrell’s murder, the police had two people in custody, one of whom was a 15-year-old boy at the time. Police arrested the minor after he went to a hospital to get treated for a gunshot wound.

The shooter in Andrell’s murder was a 25-year-old and a returning citizen after serving time for his second felony. Napper-Williams said it was a grueling trial, with three witnesses taking the stand. One of them, a young woman, was double-parked when the shooting happened. She gave motive, opportunity and identification, Napper-Williams said.

The witness saw the shooter at the park and across the street from where the shooting happened earlier in the day. When she thanked the witness for testifying in the case, she assured Napper-Williams that there was no need and that this is something that the community should be doing.

The teenager in the case immediately pled guilty, and the judge sentenced him soon afterward, but his words during the multiple hearings stuck with Andrell’s mother.

“He was 15 years old. He was promised drugs and a gun to help retaliate the murder of the (shooter’s) loved one. Their loved one had gotten killed a week prior,” Napper-Williams explained about one of her son’s murderers.

She was happy that her son’s murderers would be limited in power behind bars, but that is as far as her happiness extends. “Am I like glad that four African American young men are paying the price for one bullet and for my son’s murder? Absolutely not,” she told the Mississippi Free Press.

Building Andrell’s Legacy

Both losing her son and hearing the 15-year-old shooter testify started Napper-Williams thinking about what was needed to ensure that other children aren’t lost to the streets or to gun violence.

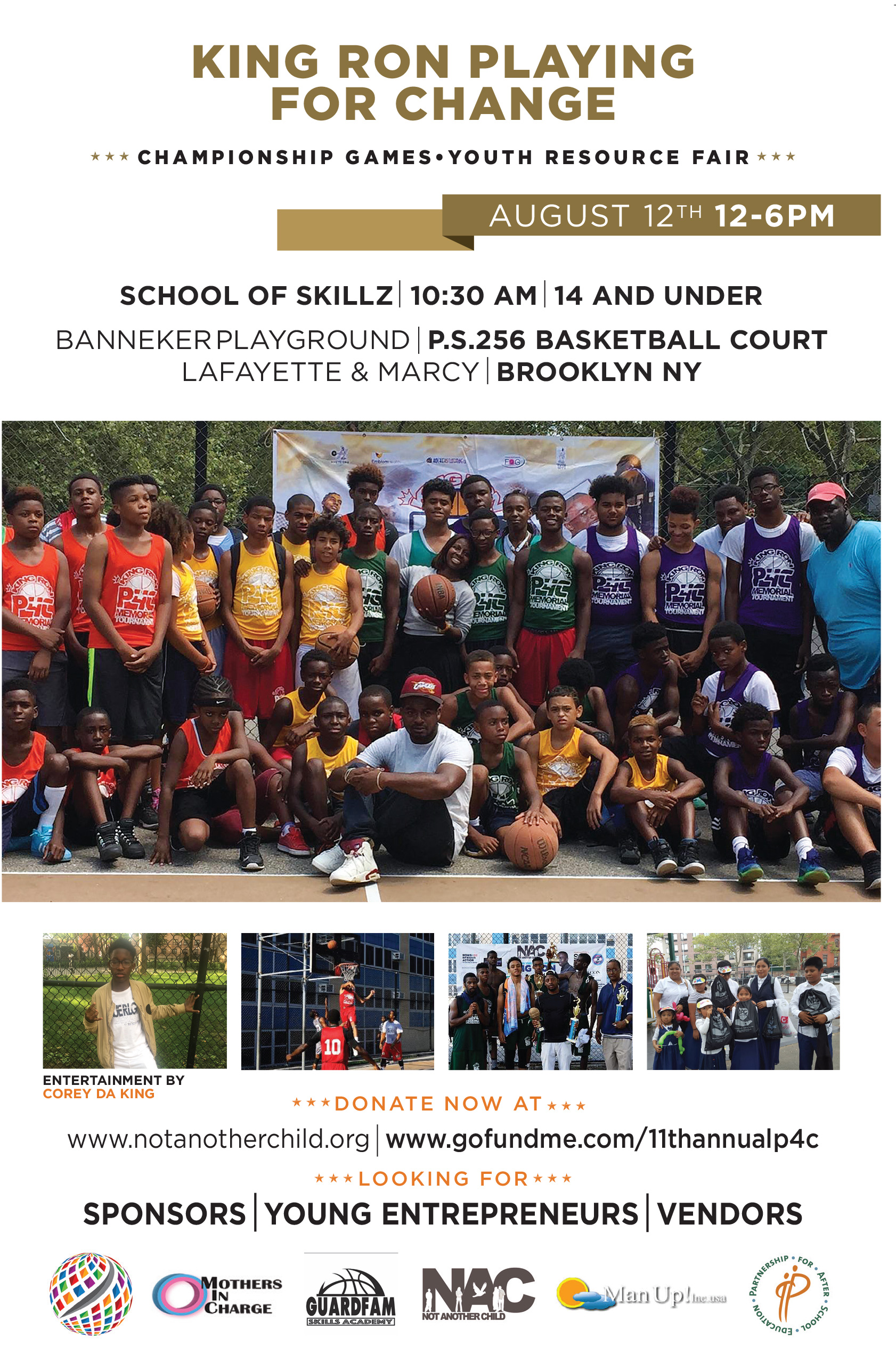

The knew that the way to communicate with young people, especially young men, is through basketball, food and music. So, a year after her son’s murder, she put together the first annual King Ron Playing for Change basketball tournament in honor of her son, whom she called Ronnie.

When the tournament first started in 2007, it was a one-day event. Over the years, the tournament turned into a summer event that starts after the Fourth of July and ends after the day Andrell was murdered, Aug. 7.

“We would pull up to the park annually (and) the kids would always run to the car … and that just melted my heart. We had teams from as far as Pennsylvania coming up to compete for this tournament, which was amazing,” she said.

Napper-Williams soon started her nonprofit organization to support her efforts to help both grieving families and to support activities for young people that could redirect them before they picked up a gun and shot somebody.

She returned to school in 2009 and received her master’s in public administration. She didn’t just want the experience, but the degree, she said.

“I wanted to have a paper as well because I always tell my parents (there are) 18 million stories in this neck of the city and by tomorrow, yours is going to be bumped (to) one out of those 18 million because there’s going to be another one that happens,” Napper-Williams said.

“So, you have to, especially with running organizations, have some type of background. I’m not saying you go to school, but you just have to put more into it than just your story because stories get stale as well,” she added.

Over time, Not Another Child grew into a nonprofit organization that encompasses various programs with the goal of helping communities of color on a global scale.

The Out The Hood project allows underexposed youth to experience career and cultural diversity outside of their daily environment through reading, research and excursions. B.U.D.S (Brothers, Uncles, Dads & Sons) is a mentorship program that pairs young people with older mentors who can give guidance, resources and wisdom.

Brown Book Boys Club is a book club for young men of color, and Heal, Recover, and Grow is a therapeutic support group for people who have lost loved ones to violence. Napper-Williams said she knows no other way but to continue fighting and keep her son’s memory alive by helping other young people stay alive and assisting their families during tragedies.

“You don’t want to let your child down that his living would be in vain and that he would go unknown and unnoticed. My son didn’t have any children to carry on his legacy or anything of that nature, so this is his baby. This is his legacy, what he will be remembered by,” the mother said.

‘You Go Through Depression’

Shaneika Green suffered another tragedy months after her son’s death. Her son, Jeremiah Blough; her daughter, Shirley Green, who was pregnant at the time; and her daughter’s boyfriend, Corey Smith, stopped at a traffic light on Lynch Street one night. A car pulled up beside them and shot up the car.

Her daughter, who was in the passenger seat, was shot in the hand, while her boyfriend was shot 10 times, protecting her daughter from gunfire. Green’s son managed to escape injury by bunkering down on the car floor in the backseat.

“It was about 10 o’clock at night. You can’t even stop at the red light at night without thinking somebody’s gonna pull up on the side (and) shoot you,” Green said.

Thankfully, her daughter’s boyfriend survived the shooting, but the trauma remains. Green said her daughter is still not mentally OK following the incident and she’s managed to get her in therapy at Hinds Behavioral Health on Highway 80, where Shirley was diagnosed with depression, she said.

“She had to get help and right now, she still has to get help for being young, pregnant and these tragedies happen to you. I don’t think she would have had depression (if) my son wouldn’t have gotten murdered and everything that went on. She has to take medicine, see a doctor and talk to the therapist,” Shaneika said.

As for herself, Green said she has her good and bad days. One minute she can be okay and the next, she can be crying.

“You go through hate. You go through sadness. You go through depression. It’s all types of emotions you go through. I hear this all the time. It’ll get better. … I don’t think it’s going to get better,” she explained.

Moving Forward with PTSD

Clinical Psychologist Dr. Julie Schumacher of the University of Mississippi Medical Center said losing a child to gun violence is a unique and difficult experience. Regardless of the type of trauma people experience, symptoms of post-traumatic stress are the same, however, when factoring in losing a child to gun violence, grief has to be factored in, the doctor stated.

“The grief can either proceed and resolve, or the grief itself can become an issue where people (are) not only experiencing post-traumatic stress, but they’re also experiencing grief over a prolonged period because they may get stuck on both,” Schumacher told the Mississippi Free Press.

Dr. Schumacher said there are people who experience traumatic loss and grieve just fine and there are some instances where people experience traumatic loss and don’t experience post-traumatic stress.

“They aren’t stuck or having difficulties related to how they lost the person, but they do miss the person,” she said. “When we lose someone, it’s not unusual around anniversaries or holidays (to) miss them more (or) have hard days. That seems to be especially the case when it’s the loss of a child”

For those where the grief doesn’t get easier over time, they might seek out help with someone like her, who can help them move forward, the psychologist said. Dr. Schumacher said when she works with people who have lost someone, she encourages them to discuss the loss with the right person or in the right space. But it’s never good to force someone to talk, she added.

“An important part of moving forward is for someone to be able to process it or move forward. But that doesn’t mean that if someone we love has gone through one of these things that forcing them to do it is the right thing because that can end up being not really helpful,” she said.

Shaneika Green said the church isn’t helping her as she often questions why her son had to die the way he did. However, she has found comfort in her mother-in-law, who lost a son to murder in 2014. The mother of six said her mother-in-law went into a deep depression and lost weight from lack of eating, but she recovered as the years went on.

“The other brother-in-law … he died of natural causes. She’s not going through depression or anything, I guess, because he died of natural causes compared to her son that got murdered,” Shaneika said.

Dr. Schumacher said traditional therapy or alternative solutions, like Napper-Williams’ healing circles, can both be useful depending on what the person’s needs are.

“It’s wonderful that we have options like that available,” she said. “I think channeling the sort of anger and the fear into a group where you can share and come up with ideas for how to improve your community, how to save other children and other families from having similar outcomes can be very useful for a lot of people.”

Emotions can consume a person, especially if they don’t have a way to channel what they’re feeling into something productive, which can be crucial in helping them move forward, Schumacher said.

“And then there might be others where just working through things individually and not having that become the event that defines the rest of their life might be an important thing for them,” the psychologist added.

Fostering Trust, and Being Present

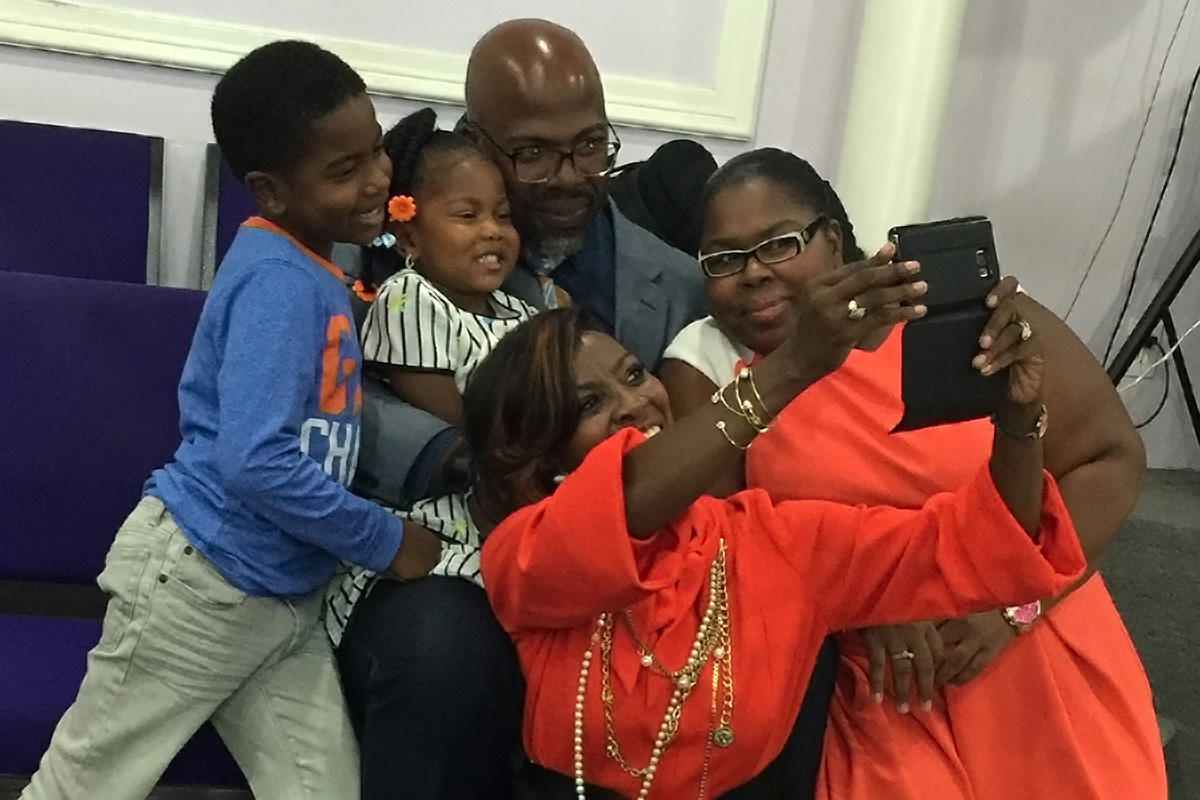

Oresa Napper-Williams’ heart still aches for families and parents who go through the grieving process without any support. To mitigate that reality, she began peer support groups for parents and family members. She gathers family members in various facilities around New York City where they can really talk. They also participate in activities such as honoring their lost children on commemorative quilts.

The main thing is that they find people to talk to who do not judge them and understand their grief.

“I really grew it from referrals and from people just saying, ‘Oh my God, Oresa my cousin needs to talk to you.’ ‘Oh my God, Oresa, I have a mother at our school whose son was shot on the last day of school and died a week later on his birthday. Can you call her?’” she said.

The mother said she originally had no strategy or structure to market her peer groups, but her emphasis on people being able to tell their stories in the presence of others who understood brought people to her through word of mouth.

Prior to bringing the mothers into the healing circle, Oresa conducts one-on-one sessions because if the mothers don’t trust anybody else, they trust her and then they go on to trust others.

“I have a plethora of mothers in my phone that I always text, and I always call, but some of them just won’t get on a call,” Napper-Williams said. “But I have six of them that I was able to get on a Zoom, and because I knew them prior, (it was like) they knew each other without knowing each other. And then, we built a WhatsApp with all of them in it.”

One of her best skills is making people know that she is pure at heart, so that trust can be fostered. From her very first interaction with a mother, Napper-Williams wants them to know she is concerned, she is present, and that she isn’t making everything about her story, she said.

“I just start with the bare basics. I can relate to you, my son was killed as well. That’s it,” the mother said.

The anti-violence activist said she has been getting her certificate in grief counseling because the process has shown her that grief and responses to grief can be determined by a person’s relationship with the deceased.

Some parents who went all out for their child can live and grieve with no regrets, while parents who may have had a more contentious relationship with their child may then live with regrets because they didn’t know that time would catch up to them, she explained.

The sessions have had a great impact on the mothers, who have ended up forming tight bonds with one another, even doing things without Napper-Williams present. Some have also followed in her footsteps of starting their own organizations to continue their legacy of their children, and she is always open and willing to help them, she said.

“NAC is at a place where I can help you guys amplify what you’re doing,” she said. “Let me know if you’re doing something, and you need our support, whether it’s me helping you raise money or whether it’s volunteers. I’m helping one of them build their board.”

‘Communication’

Napper-Williams also focuses her work on preventing young people facing the highest risk of crime and violence from getting in trouble. Across the U.S., from Jackson to New York City to Los Angeles and Chicago, that is a small percentage of young people, and then typically share certain indicators and precursors, making them possible to identify for interventions.

BOTEC Analysis reports on Jackson crime, which the Mississippi Legislature funded in 2016, show that individuals who were chronically absent in school were 79% more likely to be involved in the adult criminal justice system later and 79% more likely to be charged with a serious offense. Those who have also failed a grade were disproportionately represented in the adult criminal justice system and charged with a serious crime.

“Dropping out of school carries the highest associated risk of being involved in the adult system (160% more likely) and of committing a serious or very serious crime (220% more likely),” the report finds.

Dropping out is one of the top precursors to worse crime later, BOTEC reported, along with minors having contact with law enforcement, including being put into the back of a police car for minor offenses.

Through interviews, BOTEC researchers found that young people who ran into trouble later in life with the criminal justice system described their upbringings to be full of losses, danger and instability. The dysfunction included elements like poverty, boredom, lack of adult attention, death, disabilities or absence of parents through incarceration or addiction.

Prior to the 1970s, the goal of imprisonment was geared to rehabilitation, but factors such as rising crime rates, the belief among some that rehabilitation programs would not work and political conflict over the criminal justice system shifted toward punishment and the war on drugs.

“As billions of dollars were spent on new and larger prisons, less attention was given to rehabilitation, and some prisons became more like warehouses designed to tightly control and punish large numbers of offenders,” the BOTEC report states. It recommends programs involving outreach workers and credible messengers and prevention efforts like the Urban Peace Institute in Los Angeles.

Organized ‘Wraparound Services’ Vital

Crime and violence prevention takes getting organized and more effort than occasional events for kids, and the efforts must reach and serve the young people that precursors show are at highest risk of serious crime, Napper-Williams emphasized in a Feb. 17, 2022, MFP Live interview. Plus, those young people need the next thing in place ready when one program ends, which requires planning ahead and community collaboration.

That is, “wraparound services” are vital to prevent violence and help young people overcome difficult circumstances, she said on MFP Live.

A few years into her annual basketball tournament, Napper-Williams said she realized she wasn’t doing enough work with young people past the summertime. Young people would leave the tournaments headed toward graduation, and when she would ask their plans following high school, they were unsure, which was disheartening, she said.

“I had a young man. He used to take the score. He didn’t want to play basketball. I could see him being the owner of a team or something like that,” she recalled. “(He) graduated and came back the next summer. This boy had a baby and had to wind up taking a job. I was mad at him, but I was more mad at myself because I wasn’t up on it like that.”

It was then she started to try and keep up with young people more. She builds relationships with them and their parents that help her gain their trust, she said.

“Communicating with them verbally and text wise and letting them know what we’re doing to see if they want to be a part,” she described.

‘Challenges and Cultural Incompetence’

The need for therapeutic interventions and support for parents and children is urgent, Napper-Williams emphasizes, and requires an organized approach and community collaborations, far beyond what law enforcement is capable of accomplishing. Plus, police involvement builds distrust with those who need interventions the most and who often grow up in communities that distrust law enforcement, often due to harsh treatment from under-trained officers.

Over time, she expanded her healing circles outside of the original Vanderbilt Avenue community of Brooklyn, establishing groups in the Canarsie and Bedford-Stuyvesant communities. Her team recently finished setting up the Bed-Stuy office, which is also the newest space of community advocacy and credible-messenger group Man Up! Inc., and it will be opening the doors to the community soon.

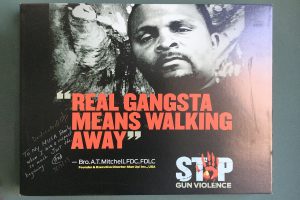

Man Up!, started by formerly incarcerated Andre T. Mitchell, is one of myriad credible-messenger programs in New York City and is based on the Cure Violence model of treating violence as a virus. The approach involves hiring and training men and women who have been in trouble themselves to mentor young people at high risk of violence, which can also reduce crime among returning citizens who have gainful employments and ways to give back. They also act as violence interrupters to help prevent the cycle of retaliation that often drives spikes in violence as someone avenges the death of a loved one.

Mitchell, in fact, came to Jackson to advise the founders of Strong Arms of JXN back in 2018.

Mitchell also works with a variety of organizations in New York City to help young people have more choices. He helped spearhead the building of the impressive Prince Joshua Avitto Community Center in East New York next to a large public-housing complex, which is named for a young Black boy killed in violence there.

At the start of 2022, Napper-Williams’ Not Another Child began services in the Canarsie community of Brooklyn. As an introduction to the community, the organization hosted a “New Year, New You” vision-board planning event, which helped give them a scope of how many young people reside in the community, how many mothers lost their children to gun violence and how they could help both.

“When I tell you (about) these young men, they were into it. They were cutting out the magazines and looking at the words. I mean, it was so good. It was so good,” Napper-Williams expressed.

But an unfortunate incident ruined the event, forcing the organization to put a pause on the work they intend to do.

”While we were there, which is supposed to be a safe space for the community, the police came and arrested one of the young men, one of the participants, who was there. It was rough. It was bad. And so, it threw what was a healthy, wholesome event completely off. We can’t have anything else there,” the founder said.

The owner of the Canarsie space is what Napper-Williams would call “culturally incompetent,” treating the attendees for her event with hostile energy. Despite the negativity, she said the community and young people did not lose faith in the organization. But the community does not want to return to the venue, so she’s looking for a new location for the sessions to be hosted, she said.

The South is rife with culturally incompetent people who refuse to acknowledge the perspective and needs of others outside their background—and who think a saturation of police sweeps is the only way to prevent crime. Napper-Williams shakes her head at that false notion. Her advice for how to handle such individuals depends on if they are apologetic or if they gloat about the behavior they display.

“If they’re the type of person that gloats in it, as I saw, (and) laugh at the things that happen, you have to remove yourself from that because that can become another project to you. You can begin to lose focus off of your work and focus on that,” she said.

Black Activists as ‘Puppets’

Napper-Williams has faced many challenges through the years of running Not Another Child and her anti-violence work. One of the biggest is getting people to take her mission seriously, and not believing she is more than a grieving mother. She has overcome that through a daily process of knowing who she is and what her purpose is, she added.

“Some of my work is based on my son, my grief, my healing, but then a lot of it also is based on making a difference in the nation and not just locally. So, being my own biggest cheerleader,” Napper-Williams said. “My persistence and my favor has broken me into a lot of rooms and put me at tables. And in some instances made me the table, so that’s what it has been.”

The mother of two said that because some think of her only as a grieving mother, she is not given larger funding opportunities, even with all her experience and on-the-ground knowledge. She has witnessed one young, Black organizer go on to have three different locations in the city, but it was through selling herself to a bigger organization.

“And I’m not doing that,” she emphasized.

Napper-Williams said bigger organizations have approached her to buy her organization, but they want to make the decisions, shape the programs, and dictate what is talked about and where. And many of these organizations start chapters that deal with crime and violence intervention work because they see an opportunity and that funds are there, the founder explained.

Napper-Williams said larger organizations feed on these grassroots organizations like chickens in a shack to make them blow up and try to overtake what grassroots organizations are doing.

“And when we come to the table, they send the little African American faces that cannot make any decisions, but they have them at the table of being the face of the organization. In this arena, they are the puppets, but I have been consistent in doing what I know to do, and that’s it. Just working it out,” she said.

Napper-Williams advises other grassroots organizations to keep focusing on their work and look for funding outside what the local government can provide. Many New York City organizations rely on the mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice for funds, depending on the work you’re doing, she said.

“If by any means you can do it full-time, do it full-time. Because although you are successful doing it part-time and doing that once-a-year event and things like that, it’s another level of success that I did not even reach until I told my husband, ‘I can’t do it any more. I can’t work in a school and do this,’” she expressed.

Napper-Williams quit her full-time job seven years into Not Another Child, and things really started to take off after that. “I’m totally transparent, I know some people probably cannot do that, (but) if it’s an option, do it,” the NAC founder said.

‘Black and Brown Peace Consortium’

Napper-Williams said she and other Black organizations across the nation formed the Black Brown Peace Consortium in 2018. The goal of the group is to receive money and allocate funds to boots-on-the-ground organizations because the majority of the time the money isn’t getting to these organizations.

Prior to President Biden’s transition to office, the White House put together a gun-violence transition committee to assess the needs of Black communities. But after Biden entered office, the committee was dissolved and the consortium patiently waited for what was next, Napper-Williams said.

“The next thing, we look up and we’re receiving a White House notice that they had met with Giffords, they’ve met with Everytown, and they also met with another white-run organization talking about how they have given them solutions to move forward with gun violence,” she said.

The NAC founder said the Black Brown Peace Consortium created so much havoc that they were able to get a call with Ambassador Susan Rice to discuss their needs. The call ended in Rice committing to being a champion for their cause and wanting to learn more about the work they’re doing.

“Our ask was also to get President Biden to raise what he did on the campaign trail of promising $800 million to communities of color for violence-interruption work to $5 billion,” the NAC founder said.

After confirming how they got to the amount of $5 billion, at the request of Ambassador Rice, the amount was added into the infrastructure package, The Build Back Better Act. The bill did not pass, however, because Democratic U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin would not support it.

“They’re getting ready to break it down, but the good thing is the $5 billion was never spoken of. With everything that he did not like in the Build Back Better Act, it wasn’t that,” she said.

Now, Napper-Williams is working with Mayor Eric Adams’ office in New York to draft a document that will outline what organizations like Not Another Child need from city agencies as part of New York’s crisis-management system.

“Let’s say the agency is the Department of Sanitation,” the founder said. “I put in there that our need is for them to remove any items, and I had in parenthesis blood, remains, anything relating to a deceased victim’s body from the place it happened within … no more than 24 hours,” she said.

Napper-Williams said many families have been retraumatized or experienced compounded trauma by stepping over their loved one’s blood, sometimes for days. She retold a story of her friend, who lost her son to gun violence two days after his birthday. The mother was at her son’s house to celebrate with him the day he was shot.

“(He) opened the door, and he was talking to somebody. She had heard them arguing … next thing she knows, she heard bullets. Open the door, her son’s body was rolling down,” Oresa recalled. “When we went back two days later to do a candlelight vigil, she had to wash her son’s blood off of the ground.”

Napper-Williams said she needs every NAC site that she has with the crisis-management system to have a survivor-led component, and she’ll do the work of making sure the survivors are trained the same way, so data can then be collected.

The founder wished she had services like these available at the time she lost her son, which is why she works so hard to provide for and assure families get what they need, she said. It’s why she has strengthened her relationship with 1 Police Plaza, the headquarters and nickname for the administration of the New York City Police Department in Manhattan.

“I’ve honed in on that, and they connect me to the inspectors of the precincts. Every precinct that our support groups will be in, I’ve already had a connection with the inspector of the 69th, the 75th, the 81st and the 23rd and 25th in Harlem, so that they know of our services, and then they advise their detectives, their community officers,” Napper-Williams explained.

‘Victims Compensation’—But Not for Everyone

Shaneika Green said the City of Jackson has a source for victims of crime, but if the violence victim has been to jail or prison, they will not offer services to help the family. Green was speaking of the Bureau of Victim Assistance, which was established to provide statewide assistance to victims of crime.

The bureau has a Victim Compensation Program that provides financial assistance to innocent victims of crimes and their eligible family members. The program is supposed to “reduce the financial burden resulting from a violent crime by reimbursing eligible victims and family members for their crime-related expenses not covered by any other benefit source like insurance, Medicaid, worker’s compensation, etc.,” the site states.

But how does the bureau distinguish between who is eligible or ineligible for benefits?

On the Victim Compensation application, those who are not eligible for benefits are: individuals who engaged in illegal activity; individuals who are the offender or accomplice to the offender; anyone injured in a car accident (unless the vehicle was used by the offender as a weapon, in a hit & run, driving under the influence, in an attempt to flee police or causing injury to a child in the process of boarding or exiting a bus); anyone in prison when the crime occurred; a victim or claimant who is convicted of a felony and it becomes known to the Division after an application was filed; a victim or claimant who has three previous felony convictions; and a victim or claimant who was under the supervision of any department of corrections within five years to the victim’s injury or death.

Tramaine Green had just gotten out of prison a month before his death, serving almost a year for burglary.

“That person, that victim, even though they’ve been to prison, they’re still a person. They don’t deserve to get killed. If they get murdered in Jackson, (the city) should stil be responsible and help,” Tramaine’s mother told the Mississippi Free Press.

Plus, helping families in times of trauma and need can prevent future crime and violence, as Napper-Williams points out.

Approval of the application could result in up to $6,500 in funeral expenses and $800 per claim for transportation costs to make arrangements and attend the funeral; mental-health counseling for the victim and their family members could result in up to $3,500 per claim and lost wages resulting in $600 per week, the application lists.

Green said she was fortunate that the majority of Tramaine’s family, friends and people who knew him stepped up and helped pitch in for his home-going service.

“I didn’t get him buried. We got him cremated because we want to feel like he’s still here. (But) it was hard for me to get that money up to have my son’s service. That was almost about $8,000, and it depends on what you get,” she said.

Such maltreatment of a family because the child they lost has committed a crime in the past runs fully counter to the ethos that Oresa Napper-Williams treats. She treats every family equally regardless of whether their lost loved one was involved in a crime when killed or had been in trouble in the past. Everyone person, and every family, needs dignity, respect and assistance, she insists.

When told that Mississippi families cannot get victim assistance or burial help if their loved one had previous felonies, Napper-Williams was outraged. “That must be a Mississippi thing,” she said.

Such punitive policies do not promote healing or trust-building in communities of color, she continued. “Just as the trauma is from beginning to the end, so is the bias that we face because of this. The only people who are really paying the penalty are the loved ones who are left,” Napper-Williams said.

“It’s one thing to continue your journey without a loved one, but the system giving punishment because your loved one lived a certain style of lifestyle is really not good. It’s harmful. Cities can only repair relationships with their people by repairing systemic protocols and bias against Black and Brown people.”

Donna Ladd contributed to this report.

This violence-solutions piece is part of the “(In)Equity and Resilience, Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” project looking at systemic inequities long facing Mississippi’s Black women and their families and institutions that the pandemic revealed and exacerbated in Mississippi. The BWC Project team is publishing what their systemic reporting and numerous solution circles with Black women revealed about three counties (so far): Noxubee (education); Hinds (violence and public safety) and Holmes (health care adequacy and access). The journalists are following up each county overview with specific solutions-journalisms pieces about problems their reporting revealed.

Also see: Jackson Advocate Publisher DeAnna Tisdale’s opening column introducing the BWC Project and reporting collaboration. Visit the full BWC Project microsite here.

This project is a collaboration between the Mississippi Free Press and the Jackson Advocate with support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Register at mfp.ms/circles to join a solutions circle to discuss violence prevention in Hinds County and beyond on March 1, 2022, from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., and write solutions@mississippifreepress.org to offer feedback on the reporting. Reach out to Kimberly Griffin at kimberly@mississippifreepress.org if you’d like to sponsor work in additional counties for this project.