JACKSON, Miss.—Damion Portis is a barber, marketer and graphic artist by trade, but he’s used to investigating his clients’ health.

“I first started in the Healthy Heart Care Initiative,” he told the Mississippi Free Press in an Oct. 18 interview. Portis runs Klean Jokers Master Barber Art Studio in Jackson. As part of a partnership with the Mississippi State Department of Health, he gave out free blood-pressure screenings to identify early signs of hypertension or heart disease.

“(The program) specifically targets those people who are disenfranchised, who may not have health insurance, and who typically do not go to get health checkups—(but) may be suffering from hypertension, diabetes and such,” Portis said. “High blood pressure is the number-one killer in the African American community.”

The program is a pragmatic concession to a real problem in Mississippi’s Black community. Lack of health insurance leads to a lack of preventative care, which results in worse health outcomes. Portis’ blood-pressure screenings served as ad-hoc interventions: on-ramps for preventative health-care for individuals who may not have otherwise encountered the medical system.

“If people have high blood pressure, we’d recommend them to their doctor,” he said. “If they didn’t have a doctor, we have a program and clinics affiliated with it that we could send their information to. And if they had an extremely high reading, they would do what they could to get them immediate health-care.”

Then coronavirus arrived. Barbershops across the U.S. faced the same grim realities as the rest of the country’s small businesses and venues for social gatherings. Brief involuntary shutdowns gave way to a voluntary evaporation of clientele.

“When COVID hit, it became a place where people did not want to be anymore,” Portis said. “And then when they did finally allow us to work in our barbershop, nobody wanted to sit in here and try to get their blood pressure taken. They wanted to get in and get out.”

Portis understood the anxiety. Information about COVID-19 was inconsistent, unclear, constantly evolving. “I’m an educated brother, but at the same time, I didn’t know enough about (the virus),” he said. “It took a while for us to become more comfortable with the information about how to move in this post-COVID environment.”

When the COVID-19 vaccines arrived, business owners and public-health officials alike finally had a tool that promised a return to some sense of normalcy. But that would take a public willing to get vaccinated. Portis, in his partnership with MSDH, found a way to grow the safety of his in-person services and continue the health-care initiatives he’d pursued in the past.

MSDH calls the program Shots at the Shop.

‘It Isn’t Too Often That We Lead’

Dr. Victor Sutton is the director for the Office of Preventative Health and Health Equity at MSDH. One of his many roles in 2021 has been to address a persistent problem—how to solve a lingering chill in Black uptake of the vaccine.

Racial inequalities in vaccine access have been a concern from the earliest days of the COVID-19 vaccine’s availability. Nationwide demographic data on vaccination rates shows a trend of visible disparities that persists to this day.

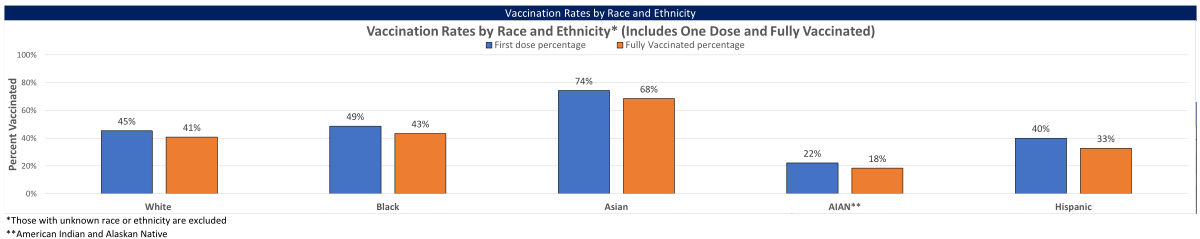

“Overall,” the Kaiser Family Foundation concluded on Oct. 5, “across these 43 states, the percent of White people who have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose (53%) was 1.2 times higher than the rate for Black people (45%).”

In the earliest days of the vaccine drive, Black vaccinations in Mississippi lingered below 30% of the total, well below the 38% that matches Mississippi’s racial demographics. Mississippi struggled with this disparity as its overall vaccine program fell behind the rest of the nation, lagging for a lengthy period of time in last place overall.

But Mississippi has since broken through an enormous barrier of vaccine disparity. The KFF study found that Mississippi was one of six states, including Oregon, Alaska, Idaho, Washington and Louisiana, that showed a higher rate of vaccination among Black residents compared to white.

As of today, 49% of Black Mississippians have received their first shot, and 43% are fully vaccinated, compared to 45% and 41% of white residents, respectively.

For the Mississippi State Department of Health’s Health Equity Team, this outcome is the result of a policy that relied upon local partners to inform, build trust, and vaccinate populations lacking in access, interest, or both.

“It isn’t too often that we lead the national average on a lot of different indicators,” Sutton told the Mississippi Free Press in an October interview. “That’s really a testament to all the great partners that we’ve been able to work with.”

Dr. Chigozie Udemgba, director of the Office of Health Equity, is the co-lead for the Health Equity Team. Udemgba highlights the key to the health agency’s approach. “It’s not only just about educating people, (it’s) making sure that they have the proper resources to disseminate it within their community,” Udemgba said.

The information and the resources that MSDH provides are vital, Portis said, expanding on Udemgba’s thoughts. But his role is to transform that raw data into persuasion, a process that often requires more nuance than simply being right. “You can give the right answer to the wrong understanding,” he explained.

Portis has seen it all. Some of his clients have had family members die tragic deaths from COVID-19. Some have experienced the terrible reality of a serious case themselves. Others have seen it pass through their immediate family with barely a whisper, inculcating a sense of disbelief in the virus’ seriousness that can be hard to dislodge.

“What information someone is (exposed) to—how much good information, how much bad information—this can make or break what I am trying to do here in my shop,” Portis said.

“They say don’t talk about religion and politics in the barbershop,” Portis continues. The intersection of pandemic policy, politics and belief makes that untenable. “COVID supersedes both of those, because you’re talking about a person’s beliefs and their politics, putting them both on display. That gets into the dynamics of who we all are as individuals.”

Trusted Individuals

The Health Equity team underscores the importance of public trust. “We put out a … vaccine hesitancy survey that served as a basis, a foundation for getting that information,” Sutton said.

“We saw the range of who folks really listened to: who were those trusted individuals? That served as the cornerstone of some of our outreach efforts. So we did work with the faith-based community. We work with community-based organizations,” he added.

Sutton explained that this vaccine hesitancy survey helped MSDH identify where Mississippians placed their trust, and who might be capable of carrying a message about the importance of the vaccine further than the state health agency alone.

Many Mississippians reached out to get vaccinated the moment the shot became available, signing up through an MSDH website to schedule a quick drive-through at a Mississippi National Guard-staffed site. The medical system intercepted others through regular doctor’s visits or trips to the pharmacy.

Now that roughly half of the state has had at least one shot, the Health Equity Team’s job is to find ways to reach an increasingly smaller remainder. Community events were always going to be key to that effort, but Sutton said the early days of the Health Equity Team’s research revealed how necessary planning was to ensure those events actually mattered.

“Just because you have a vaccination event in a community, it doesn’t mean that the community is aware of it,” Sutton explained. “We’re conscious that folks in certain communities might not go to an area of town, even though it may be a quarter of a mile away. So we listen to the community about where best to have these events—who should be involved in getting the word out.”

Part of the program moving forward is to push conversation about the vaccine deeper into communities than traditional outreach can manage. This is where Shots at the Shop comes in, a program that pays barbers to complete an educational course on the virus and the vaccine and to assist MSDH in vaccinating their community.

“They do receive a stipend, but they’re going to have to go through a two-hour training around COVID, have educational materials in their shop—a display, to be able to share that information. And they’re going to work with the health-equity team and our team (on vaccine events) at the shop or in their community,” Sutton said.

Sutton and Udemgba also see the barbershop as a social intersection that can disseminate factual, valuable information across entire communities.

“Barbers have connections with so many different types of people,” Udemgba said. “You have health-care professionals, you have truck drivers, whoever can come into the shop—all types of people, and they’re connected.”

‘The Truth Is, I’m Not Neutral’

Portis has those connections, and draws on them to communicate the necessity of the vaccine to his clientele. Often, Portis adds, that communication has to take the form of listening. “Understand that African Americans have definitely, in times past, been on the experimental end of health care,” he said.

Tuskegee is not merely a buzzword to Portis, an expected shorthand for past manifestations of medical racism against Black Americans. Portis attended Tuskegee University as an undergrad, once the Tuskegee Institute, the location of the destructive syphilis study between 1932 and 1972 that withheld treatment from 600 infected Black sharecroppers for clinical study of disease.

“These things are passed down,” Portis said. “It wasn’t that long ago, and it’s not an abstract concept for me.”

This historically warranted skepticism of the medical establishment is another reason community partners are key to MSDH’s strategy. “If you’re going to be successful in community engagement, and this sounds very, very basic, but you’re going to have to involve the community,” Sutton explained. “(Because) oftentimes you think you have all the answers, but you really don’t.”

Portis sees that confidence as a major stumbling block to effective persuasion. “Everyone has a need to be right, for whatever they believe in. If I decide to get the vaccine or if I decide not to do it,” he said.

There is the crux of Portis’ strategy, the culmination of why his relationships paired with the knowledge and resources of MSDH may prove to be a winning combination. He doesn’t have to fight.

“My successful conversations come from a neutral stance,” Portis said. “I present information. I allow them to figure it out (for themselves).”

His big wins, Portis says, don’t come from arguing the skeptical into submission, but allowing them to come to the right conclusions with the help of accurate information. “And the truth is, I’m not neutral, because I am vaccinated. And they know where I stand because of that fact,” he said.

In the era of social media, Portis explains, we are all bombarded with information, some good, some bad. Persuasion is more about presenting the good information from a trusted source, in the right environment, and simply allowing people the opportunity to convince themselves.

Trusting motivated individuals like Portis, rather than dictating a one-size-fits-all approach, Sutton explained, allows informed leadership to fill in the gaps and the blind spots that a statewide agency might not otherwise have. At the same time, it is the state’s ability to marshal coordination, resources, and support that provides those individuals and teams with necessary resources and information.

The Health Equity Team’s job is far from over. While vaccine uptake for the state’s Black community has now exceeded that of the state’s white demographic, disparity is still strong in Mississippi’s Hispanic and American Indian and Alaskan Native populations.

Udemgba explained that work continues in building the state’s task forces dedicated to reaching specific populations to extend the protection of the shot. Where Mississippi’s existing partnerships were strong, the work happened more quickly.

“This was an opportunity (to ask) how we build better relationships with those communities. We started from the ground up looking at some of those community leaders, building those networks and relationships,” he said.