After COVID-19 showed up in rural Noxubee County, Miss., in mid-March 2020, Shawanda Readus’ living room became a classroom. Noxubee County Schools closed the same month, so she brought desks in to accommodate her three children, but the single mom quickly realized that they cluttered her small Cedar Creek home in Macon, the county seat, so she removed them.

Readus was a server in the Noxubee County High School cafeteria when COVID-19 reached Mississippi. After the pandemic hit, she helped prepare and pack the meals that students could pick up to take the place of in-school lunches.

It was tough on Readus, as she was trying to earn a living at the school, even as it was closed for classes. The single mother spent hours on the phone with her children trying to ensure they were logged on at home. “It was hard because you are at work, and you have to call all day and check on them. They are calling you all day saying, ‘Mama, I don’t understand.’”

Eventually, Readus’ mother had to step in and sit with the children, a 12-year-old daughter and 14-year-old twin sons, during the day. “It kinda took a toll on her because she is retired, but she had to sit here everyday to make sure that they did their work, like she was the teacher,” Readus said about her mother, Sadie King-Allen.

Readus only owned one laptop, and her mother brought over her tablet. That still left one child using a phone to log in to complete assignments. They used cell phones as hotspots.

“We tried to get internet, but where I live they kept saying I wasn’t eligible to get it,” Readus said later. Mostly rural Noxubee County is all the way over bordering Alabama in east central Mississippi. “They didn’t have the fast speed like I needed. They had something that would last like two or three days, and then it’s gone, which wouldn’t have done us any good.”

By July 2020, with her kids officially out of school for the summer, Readus contracted COVID-19 herself, but was not sure where she got it. She lost her appetite and was nauseous, fatigued and lethargic. She arrived at her doctor’s office to be tested and gave a blood sample to the nurse hidden behind PPE.

The Chosen to Care Medical Center in Columbus, Miss., didn’t have the nasal swabs then needed to test her for COVID-19, and the blood-test results would take more than a week to be processed. The recommended quarantine was difficult for the mother of three, but she returned home. Her symptoms were mild, so Readus simply ignored the recommendations and continued about her daily tasks.

Luckily, her children did not get sick.

The Noxubee County School District was one of only a few across the state that did not reopen in the fall to in-person learning for the 2020-2021 school year. Now, more than 20 months after COVID-19 hit Mississippi, districts like Noxubee in areas with dwindling resources are left trying to figure out how to move forward. Navigating the pandemic is especially difficult due to disparities that the coronavirus magnified for many families served by Mississippi’s public schools. In Noxubee County, 98% of the student body is Black in an area where 41.3% of the families live below the poverty threshold of $26,500 a year for a family of four.

A 2019 Institutions of Higher Learning’s University Research Center study found that 13.1% of Noxubee households, like Readus’, consisted of children under 18 with a female householder and no spouse present.

Local educators and administrators, many of them resilient Black women, are determined to make it work and find solutions that their students and families deserve. But that is a challenge now, just as it was before the pandemic hit, due to long-term disparities and historic and intentional inequities that made the effects of the pandemic especially acute for the Black women of Noxubee County and their families.

What Once Was: History of Inequity and Violence

Noxubee County is littered with the remains of what once was. A Saturday evening summer ride through downtown Shuqualak, this journalist’s hometown, reveals a proverbial ghost town. A concrete slab is all that is left of the Shuqualak Glove Factory, which at one time was one of the town’s most prolific employers. Crumbled brick lies beside an open space that once housed the Shuqualak Medical Clinic. Boarded businesses line one side of the main street. Abandoned train tracks frame the other. The 85% Black town no longer has a grocery store; the last one sits boarded up. The poverty rate was 37.5% as of 2020, and the population has steadily declined with an individual median income of $13,656 in 2019, before the pandemic hit.

The county seat, nine miles north of Shuqualak, has fared slightly better, at least visually. The main street of Macon still houses some of the same businesses that white families started there decades ago. Now run by the third, fourth or even fifth generation, they reflect the staunch familial ties that still abound in the county. Sprinkled between them are new businesses: a lawyer’s office, a clothing store, an event hall. A local white man owns the county’s only full grocery store, Tem’s Food Market, and Black families often complain that they have to drive up to Lowndes County for more reasonably priced groceries.

Even though Macon has a higher white population than Shuqualak at 14.8%, its poverty level was also higher at 36.7% in 2020.

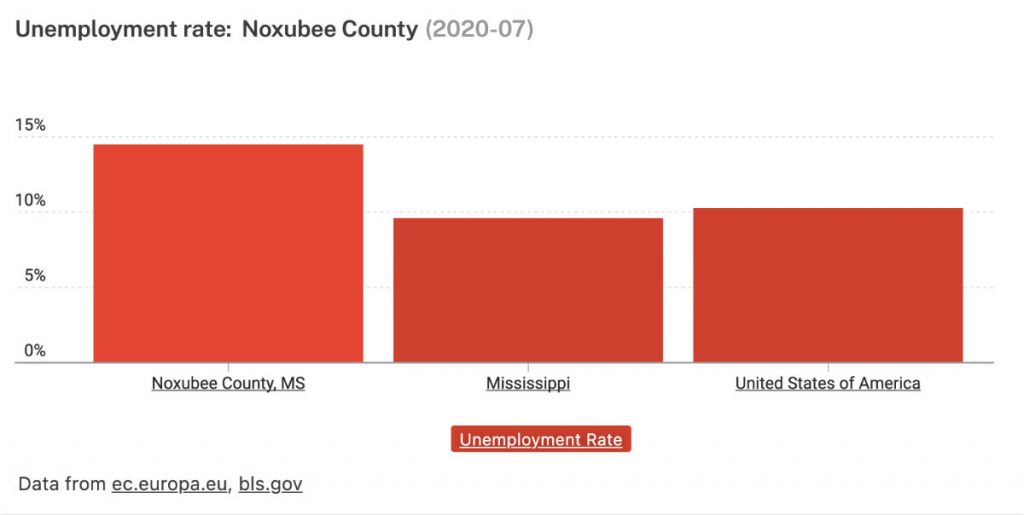

Both population and jobs have steadily shrunk in the county and in Macon. Overgrowth surrounds an abandoned factory on Highway 45 South. Left neglected, it is a striking reminder that much of industry has left the county, taking jobs and livelihoods with them. Right outside town on Highway 14 West, scraps of bricks are all that are left of the once-thriving Boral Bricks, which closed in 2007. Outdoor Technologies followed the next year. They weren’t the only ones.

Noxubee County does still have a Confederate statue on its courthouse lawn, however. Within a month of George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota in May 2020, editor Scott Boyd of the Macon Beacon newspaper called for the statue to be moved to the masonic Odd Fellows cemetery. Last we saw, it was still on the northwest corner of the courthouse lawn across the street from the former jail, complete with gallows, that is now the public library.

Like a Delta County, But Not

Noxubee is like a Mississippi Delta county—but more than a hundred miles from the actual Delta. Today it consists of three small rural towns—county seat Macon; Shuqualak; and Brooksville—with other earlier towns now extinct. Names like Shuqualak are indigenuous; the great Choctaw Chief Pushamataha was born about 1765 on Noxuba Creek near present-day Shuqualak. Noxubee is a Choctaw word meaning “stinking water.”

As a leader under pressure from a U.S. government bent on expansion and cheap property, Chief Pushamataha negotiated with the United States for compensation for continual theft of Choctaw lands, but after his sudden death during an 1824 lobbying trip to Washington, the white man’s pressure and subterfuge would win out. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, signed Sept. 7, 1830, in a clearing in Mashulaville, cleared the way for the federal government to remove 90% of Mississippi’s Choctaws west on the Trail of Tears over time, amid broken promises to the Choctaw tribe. This allowed white wealth-building to race full-speed-ahead on the fertile lands at the southwestern tip of Appalachia, worked by enslaved African descendants.

At least two of the Choctaw signers of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek at Mashulaville in Noxubee County, Chiefs Greenwood Leflore and Mashulatubbee were among Choctaw leaders who enslaved African Americans. In the century following the treaty, Mashulaville was the site of rampant white-terrorist violence and attacks on free schools for Black and white students after the Civil War.

Today, .3% of Noxubee residents are Native American.

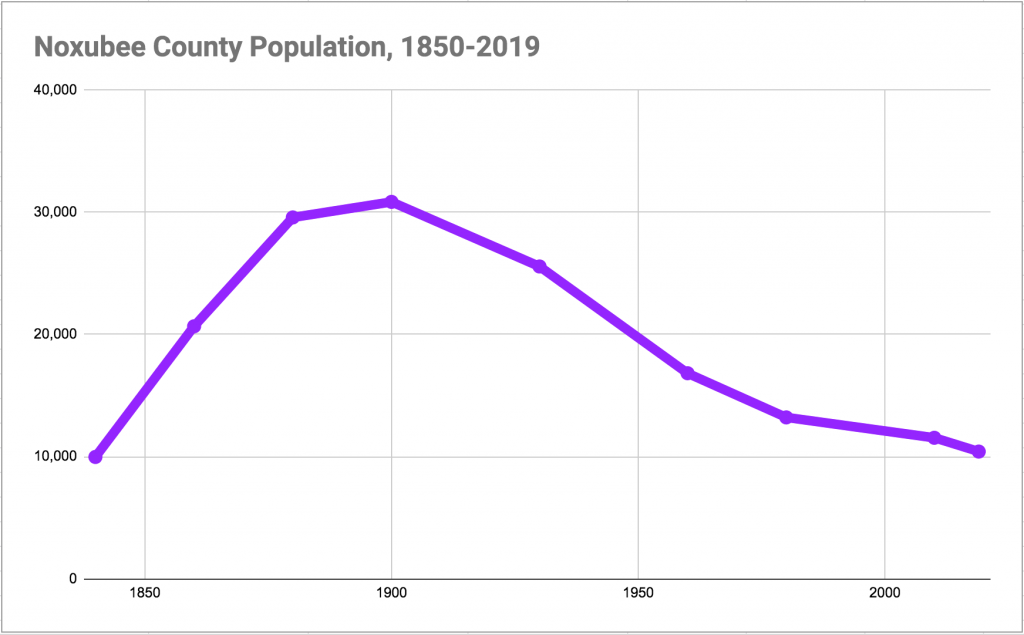

Today, the 10,284 Noxubee County residents are 72% Black with an average income of less than $34,000, an outgrowth of the county’s history as a wealthy outpost of plantations originally owned by wealthy planters mostly from the East Coast. Thousands of enslaved people worked the lands for planters, many with last names still prominent in the state today. Black people have outnumbered whites in Noxubee since its inception with 3,818 free people and 6,157 slaves in 1840, jumping to 5,171 free and 15,496 enslaved by 1860, 75 percent of the total.

The rich, stolen land made the area ripe for agricultural production for men like Major Thomas Garton Blewitt, the grandfather of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s wife, Regina. After inheriting the 270-acre Devereaux plantation (also referred to as “York”), Lee tried to keep it profitable without free labor after losing the Civil War, even adding 500 acres to it.

But, as historian Herman M. Hattaway wrote in his 1969 thesis about Lee, then in his later biographies, Lee gave up, taking the wealth from slavery spoils to own large homes in nearby Columbus in Lowndes County. He later helped found the Mississippi A&M University (now called Mississippi State University) 35 miles from Macon in Starkville in 1878 for white men of all classes, not just the planter elites.

Education innovator Lee also helped lead efforts to censor racist goals of the Confederacy out of southern textbooks and helped write Jim Crow laws into the Mississippi Constitution in 1890 to stop Black voter participation, equal education opportunity and wealth-building.

Between the mid-1800s and early 1900s, Noxubee County ranked in the state’s top 10 producers of corn, oats, livestock, cotton, sweet potatoes and in the total value of its farms, and wealth for white settlers flourished then. It was also a destination for Black Americans looking for better lives after Emancipation making the county one of the state’s most populous then. Many Black tenant farmers gathered in Noxubee seeking steady income, but the population started its dramatic slide by the 20th century with limited living-wage opportunities and high cyclical poverty, especially among Black residents.

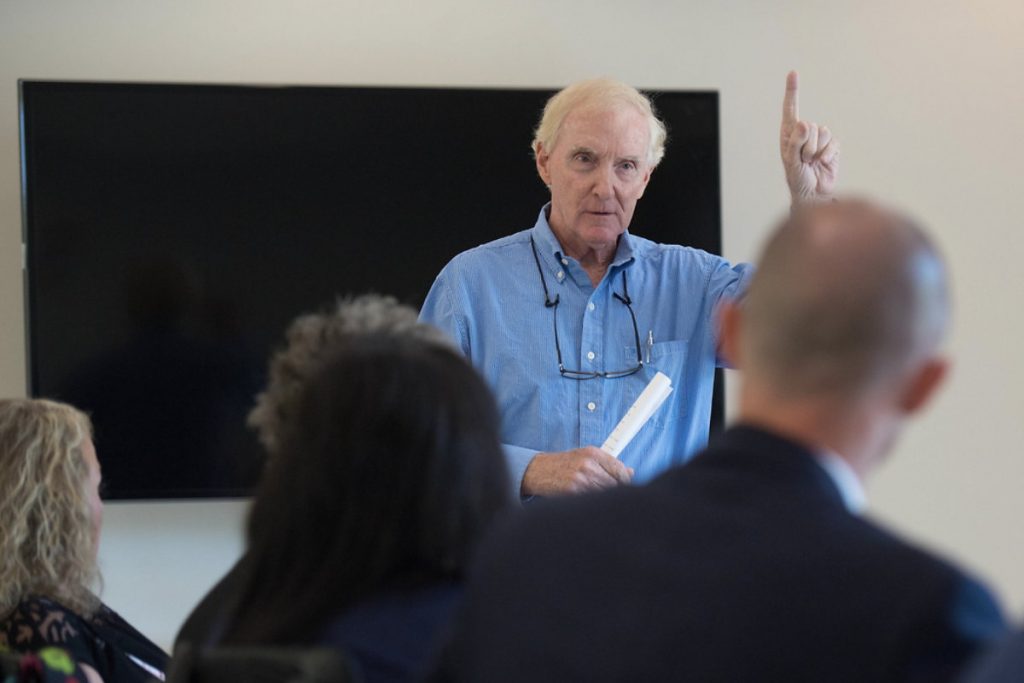

“Just like many of the Delta counties, (Noxubee) has lost a lot of its citizens Black and white because there are fewer jobs, and for skilled laborers there are few,” said Dr. Andrew Mullins Jr., now-retired assistant to the chancellor and associate professor of education at the University of Mississippi, who fondly recalls growing up on what is now Old Highway 45 in Noxubee County.

“Those who worked in agriculture for years didn’t get any training, just manual labor skills. Those jobs have decreased considerably. It’s just a dying area like so many counties in Mississippi that were totally dependent on agriculture.”

Mullins has deep family roots in Noxubee County. His great-great-great grandfather Joel Barnett was one of the earliest settlers of Noxubee County and a wealthy slave owner. He migrated there after Virginia and then Georgia looking for new land to farm. Barnett’s granddaughter married a Poindexter whose family owned the Ravine Plantation in northeast Noxubee County near the Alabama border. The family moved inside the Macon city limits in 1920. The house that Mullins’ grandfather built still sits across from the town’s only grocery store. His father ran a local hardware store for more than 50 years. The store, started by his grandparents, supplied local farmers both Black and white.

“Where you had a high population of slaves, you have a high population of African Americans today, but Noxubee County has one of the highest African American population percentages of any county east of I-55,” Mullins, this reporter’s former professor at the University of Mississippi, said in a phone interview.

“Where you had rural areas that were dependent on one crop and dependent on slave labor and then freedmen labor, you don’t have much education because of the poverty. High poverty and generational poverty generally yields low academic achievement.”

‘They Didn’t Have Time to Plan for It’

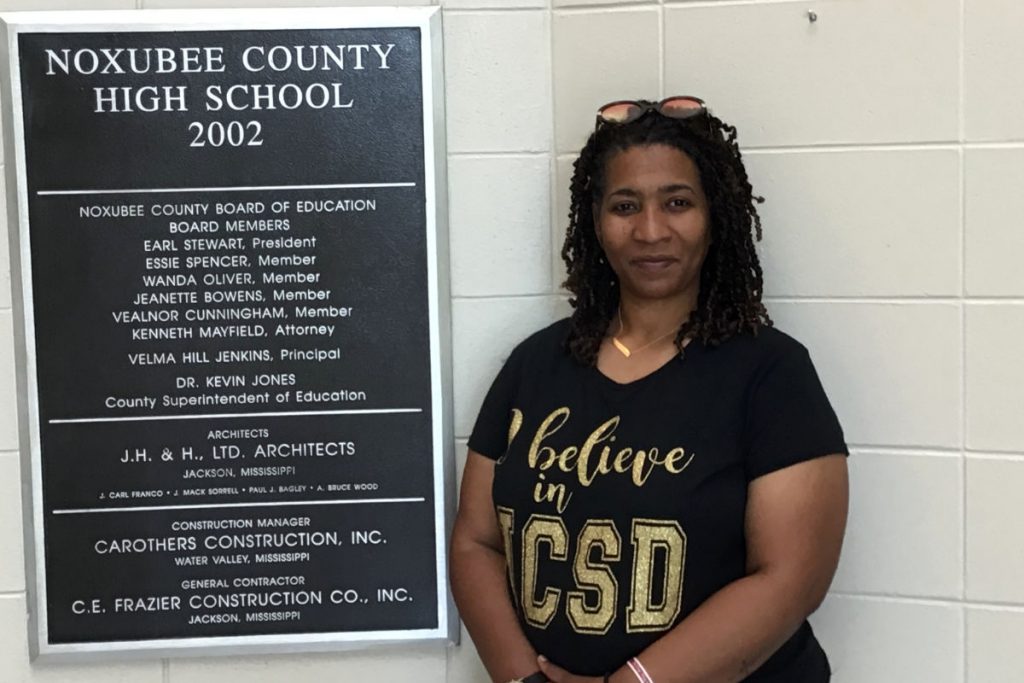

Dr. Travonder Dixon-McCloud, a clinical psychologist for the Noxubee County School District, sat in the high school library in Macon that now serves public-school families for the entire county thanks to multiple school closures and consolidation. Sunglasses on her head pulled back her gold and brown twists; she wore a black and gold t-shirt proclaiming “I believe in NCSD” over plaid leggings and polka-dot sandals on a toasty mid-June 2021 afternoon. She checked her phone quickly, remarking that the day in the consolidated school district, under State of Mississippi takeover since 2018, had been a busy one.

That same hour, sixteen months into the pandemic, the district’s state-appointed superintendent had just announced he is leaving the district to accept a job elsewhere. McCloud spent a few moments pondering who will replace him before turning her attention back to the discussion of race and education in the county where she grew up.

The conversation turned to the 1919 Macon race riot. The Memphis, Tenn.-based News Scimitar, a Black newspaper, reported on June 9, 1919, that a mob took three prominent Black residents—one of them a principal at a Black school—“across the river and gave them good advice.” Then, the paper said, the next night a mob took a Black local “across the river” for allegedly drawing a pistol on a planter; that person “has not returned.” The Columbus Dispatch reported then that the riots allegedly began after a local Black man returned from abroad and organized Black workers in pursuit of better pay and work conditions.

“I remember my great-grandmother talking about that,” Dixon-McCloud said, sitting in the school library. “She said they had their own school. … She told me that it was a lady Black principal who had a one-room schoolhouse, and my great-grandmother was a teacher in that one-room school. She said they killed (the principal). They didn’t hang her, though. It was something to do with water.” That was likely the Noxubee River, at least based on accounts of other attacks on Black people in Macon by “taking them across the river.”

Some never returned, leaving other Black people wondering if they were killed or just scared away. Both could be true through much of Noxubee County’s violence race history, much of which target Black schools and teachers to stop educational advancement.

Dixon-McCloud’s great-grandmother, Emma Lou Martin-Brooks, had completed the eighth grade, the highest level that she was allowed to at that time, and she had been selected to help teach younger students at the Black school that the mob targeted. That dedication to education and advancement helped her descendants to become well-known and respected in the community. Her grandfather served on the city’s police force for a number of years. Her father, a long-time member of Macon’s Board of Aldermen, also worked as the street commissioner.

The school psychologist graduated from Noxubee County High School in 1989 and attended historically Black Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss., the North Mississippi birthplace of reformer and anti-lynching journalist Ida B. Wells. Both Dixon-McCloud’s mother and an aunt served as nurses in the area hospital and health department, and her uncle led the school district’s security service for many years while also working as a police officer in Macon. Several of her siblings, cousins and family members still reside on Baptist Hill where a street is named after her grandfather, and the family has recently opened a local eatery.

The family, and Dixon-McCloud in particular, is fully invested in the community and the school system.

Because of her deep roots in the community, Dixon-McCloud immediately recognized in March 2020 that the coronavirus had the potential to be devastating locally and to Mississippi, a state known for its lack of financial resources, negative health outcomes and crumbling infrastructure—all of which have disparate impacts on Black communities that, left largely unabated, spiral forward through generations.

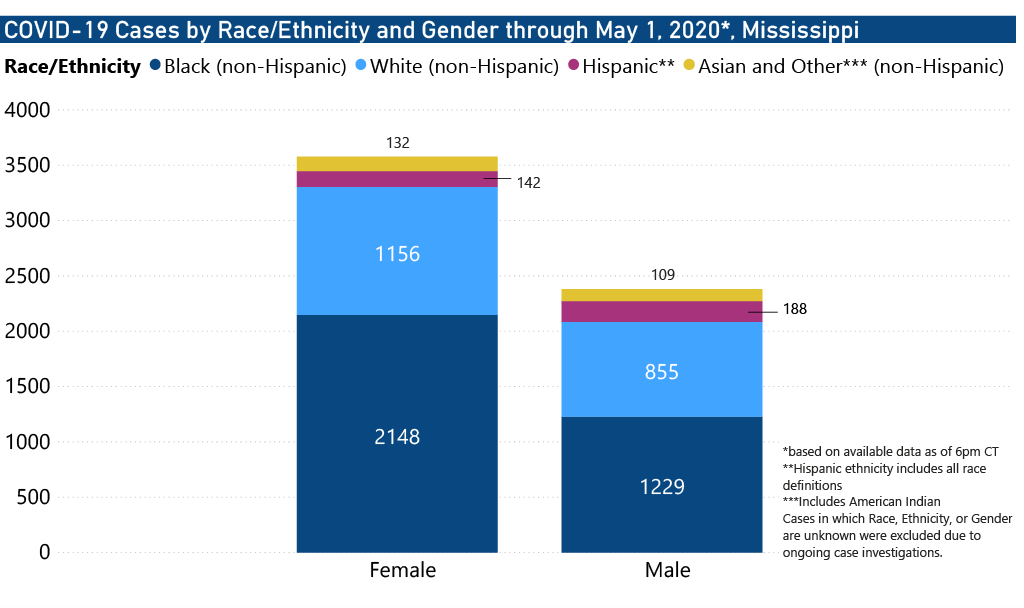

For a county such as Noxubee, significant issues loomed on the COVID-19 horizon that were magnified and spotlighted as the virus began its disparate devastation of Mississippi’s Black communities and, in particular, Black women in early months.

White Flight: Stain and Drain on Public Education

White kids like Andrew Mullins, a lifelong advocate for quality public education for all children regardless of race, enjoyed a legacy of quality schooling and opportunity. His ancestor, plantation owner William Rice Poindexter, opened one of the earliest schools in the county. The private Calhoun Institute was a pre-Civil War school for white girls located on the site of the former Noxubee County High School, which now houses administrative offices for the consolidated district. (Calhoun even served as the temporary state capitol from 1864 to the end of the Civil War.) Mullins’ mother taught math at the segregated white public school in Shuqualak in the late 1930s.

Mullins graduated from Noxubee County High School in 1966 when it was still segregated, escaping the imminent white and economic flight into segregation academies across Mississippi. The now-closed Central Academy in Macon would quickly ensure re-segregation and a drainage of resources from what would soon become majority-Black public schools across Mississippi. Central Academy was one of the state’s “seg academies,” run by the former Noxubee County school superintendent and a nonprofit foundation that continually got into legal trouble for overt racial discrimination.

White flight from public schools after forced integration is a statewide stain and drain on educational resources, but rural counties like Noxubee that have long been majority-Black have struggled even more than most to keep schools funded and populated, afford quality teachers and have access to the same amenities as whiter schools. Much like the Delta and other poor parts of Mississippi, education struggles and neglect have plagued Noxubee County for many years.

Equalizing access to quality education for the less-privileged, including Mississippi’s descendants of slavery, has met many legal and political roadblocks in Noxubee County and beyond. Many came from white Mississippians who were fine with the government paying for white public schools before integration, but who suddenly were against what some call disparagingly “government education” once the resources no longer disparately benefitted white families.

That history means that the vast majority of people of Noxubee County have always been robbed of adequate resources in health care, jobs and especially access to resources necessary for consistent quality education for its children. Those inequities were passed forward and magnified like perhaps never before when COVID-19 hit Noxubee County and its schools with battles to keep public schools even adequately funded pitted against efforts of many white families for vouchers to move their tax dollars into majority-white academies.

Black children get what’s left over after others flee with their portion of the tax base, whether their schools or the county as a whole.

The current state of Noxubee County public schools, after various white flight to private schools—even including its Mennonite schools started in 1970—is a haunting reminder of how integration never really came to Noxubee County. It wasn’t like most Central Academy families suddenly had a change of heart about going to school with Black children or needed reinvestment into local public schools. White student enrollment in Noxubee Public Schools plunged from 829 in 1967 to 71 in 1970 when Central Academy opened.

“That was a really tough time in the fall of 1971 and the spring of 1970. You had several superintendents in the state commit suicide,” Dr. Mullins said. “It was just tough for both Blacks and whites because you were undoing by federal force what had been in place since 1870.”

Growing up in Noxubee County has always meant attending segregated schools, even post integration. “I can remember where white teachers who were working in our district would teach their children how to drive beginning in the fifth grade, so they could drive to the surrounding county schools like Winston Academy and Kemper Academy,” Dixon-McCloud said in the library. “We had one (teacher) who sent her kids to Alabama.”

The closure of Central Academy in 2017 did not solve those issues, however.

“Instead of those kids coming here, they went on to Kemper Academy,” principal Aiesha Brooks said about another historic seg academy in the next county west of Noxubee. “Believe it or not, we still have teachers here who still send their kids to the academies.”

Education Mask Straining and Cracking

In the years just prior to the pandemic, the Noxubee County education mask began to strain and crack. In 2018, then-Gov. Phil Bryant approved a state takeover of the district, citing financial and academic concerns. The Mississippi Commission on School Accreditation and the State Board of Education had one week earlier declared that an extreme emergency situation existed after the findings of an audit found the district to be in violation of 81% of the state’s public-school accreditation standards.

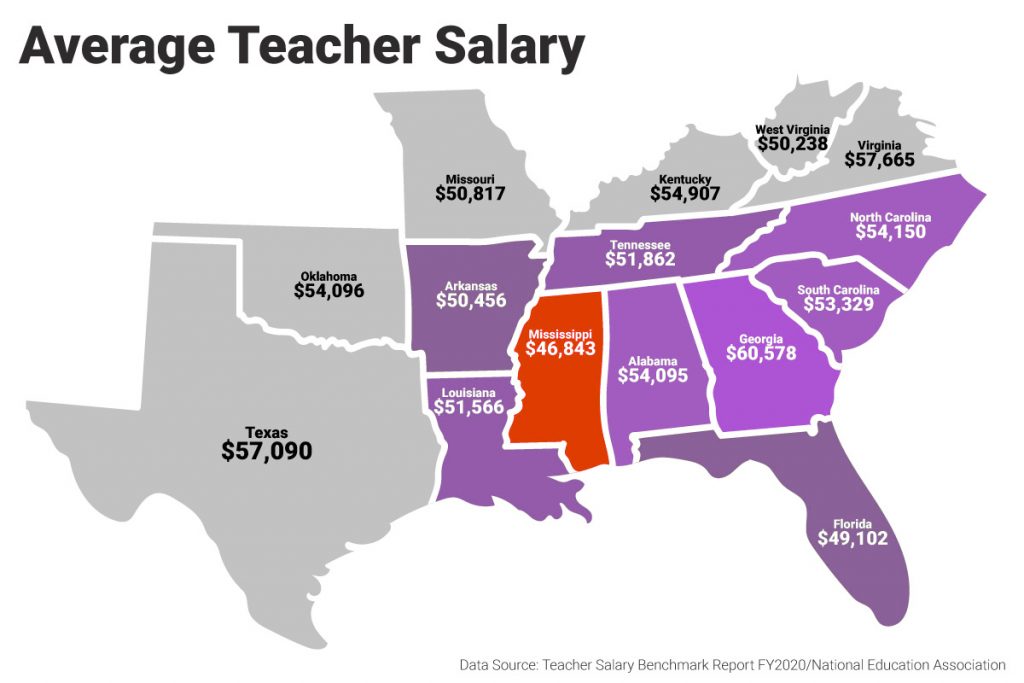

Concerns included the district’s financial state including its ability to make payroll and academic infractions. Many in the area blamed the issues on the underfunding of the Mississippi Adequate Education Program, a legal funding formula that annually falls victim to partisan politics, leaving districts like Noxubee scrambling to fund teacher salaries, classroom materials and basic utilities such as heat and air. The Southern Regional Education Board reports that the average starting salary for Mississippi teachers with a bachelor’s degree in 2018-2019 is $34,390.

By year 15, that average increases to only 40,825. In March 2021, Gov. Tate Reeves signed a bill giving teachers across the state a $1,000 annual raise. In his remarks at the Neshoba County Fair, he noted that Mississippi is still 37th in teacher pay when adjusted for the cost of living.

The Mississippi Parents’ Campaign reports that per-student funding in Mississippi is less than that of nearly every other state. Even neighboring states of Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee spend, on average, $1,200 per student more than Mississippi.

Still, with the state takeover the local NCSD school board was dissolved and the superintendent removed, leaving the leadership of the district in the hands of a state-appointed superintendent, Rodriguez Broadnaux, who left in summer 2021.

Under the plan, the district must maintain an accountability grade of C or higher for five years before local control can be restored. It was the first state takeover of a school district since Tunica County Schools was named a District of Transformation in 2015 for poor academic performance and for violating 22 of 31 state accrediting standards then.

The Mississippi Department of Education attempted to take over Jackson Public Schools in the capital city in 2017, but a coalition of JPS supporters stymied the plan, at least for now. Since the passage of the law allowing the Mississippi Department of Education to take control of schools that do not meet the accountability criteria, 16 school districts, including three that have been taken over twice, have been under some variation of state control.

Most recently, the Holmes County School District has come under MDE governance. The district, which has approximately 2,500 students, is 99% Black. The most recent census data showed that 33.8% of Holmes County, on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, lives in poverty.

A ‘Put on a Good Face’ Mask

Like similar “re-segregated” and almost fully Black districts across Mississippi—usually with segregation academies like Central still nearby—teachers in Noxubee County’s public schools say they have long dedicated themselves to providing the best education despite often inadequate resources and political attacks on public education designed to under-fund them.

“Even with nothing, we’ve been innovative and creative in getting it done,” Noxubee County High School principal Aiesha Brooks said in summer 2021. “We are human-resource rich.”

Noxubee educators’ put-on-a-good-face approach about the disparities in resources that continually erode education quality was often so good that students didn’t realize that their experience was not the norm until the graduates had moved on to other places.

For many Noxubee young people, including this reporter, college would be the first realization of missed opportunities and experiences in schools back home. We grew up not knowing what we didn’t have available to us.

Shawanda Readus realized the voids in her own Noxubee County education in college. She graduated from Noxubee County High School in 2001 and went on to East Mississippi Community College in nearby Scooba. That tiny Kemper County town is known as a college football proving ground but with a line of decaying buildings left in its small business district. Once on campus, with its huge, gleaming football stadium, Readus quickly knew that there was a learning gap.

“There were some subjects that were like a foreign language to me,” Readus said frankly in a phone interview. “We didn’t have it (in Noxubee County). Then when I got to Mississippi State, I was like ‘uh uh. I’m about to go get a job.’”

Andrew Mullins dedicated nearly 50 years of educational service to Mississippi, trying to change this very trajectory. He was special assistant to two governors and three state superintendents of education. As a member of Gov. William Winter’s staff in the early 1980s, Mullins was one of the “Boys of Spring,” the Winter team that helped engineer the landmark Education Reform Act of 1982—the first and arguably only substantive investment in public schools across race lines Mississippi has ever seen.

The act established a compulsory school-attendance law including the employment of truant officers; created publicly funded kindergarten; required the hiring of teaching assistants; and increased teacher salaries. It also implemented a statewide testing program for performance-based accreditation of public schools.

Mullins co-founded the Mississippi Teacher Corps with Harvard journalism student Amy Gutman in 1989. As the director of MTC, he placed more than 750 teachers in school districts across the Delta and north Mississippi. That included his home county.

“I tried to put as many of them as I could in Noxubee County because they needed it so desperately,” Mullins said.

“You cannot overcome the damage of 150 years of slavery and another 100 years of second-class citizenship in one or two generations,” he continued. “In Noxubee County, you’ve got 70% of the population that was adversely affected by that 150 years of slavery and another 100 years of second-class citizenship. You can make progress, but you’ve got a deep dark hole to crawl out of.”

The idea of helping the Noxubee district climb out of that hole is what drives Dixon-McCloud and Brooks to stay and work for greater school equity and opportunities for local young people.

“When I look at (these) kids, I see myself,” Brooks said. “Had it not been for my love of Noxubee, I would have been gone.”

The Block Party Never Happened

B.F. Liddell Middle School principal Holli Jenkins went live on Facebook on April 2, 2020. At the time, schools had been closed for three weeks. In the previous weeks, she had posted links for her school’s online learning apps IReady and IXL and downloadable packets on the same page.

She and several staff members were on campus handing out physical packets to students who had not yet been able to access them. She listed each grade level’s pick-up time and encouraged parents to help their children log in and complete assignments. Near the end of her live video, she congratulated the students and teachers for their performance on the third-term district test.

“We’re going to celebrate,” Jenkins said. “We’re going to have a block party. … It’s already been OK’d. We just have to get permission from the (Centers for Disease Control) and the governor to come outside and play again.”

That block party never happened.

As administrators, staff and educators prepared to finish the spring semester of 2020, they found themselves facing myriad obstacles.

They used packets of worksheets to finish the school year. However, multiple students did not have transportation to retrieve the assignments, and many of those that did would have to drive 20-plus miles each week to pick up and drop off the work.

However, district officials recognized another staggering problem. For many of the district’s students, the two meals provided during the school day are their primary source of nutrition. In an agricultural county where you can buy a variety of produce from roadside food stands where local farmers sell their crops from the back of a pickup truck, more than 99% of the students are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

To compensate, the district set up meal pickup services across the county. Families picked up boxed lunches, fruit and milk cartons at satellite locations throughout the area. At one spot, volunteers handed out meals from a bus parked in the vacant parking lot of the town’s former grocery store, which closed years ago. However, there was a lack of variation with the selections, and by August the community satellite locations were discontinued and families had to pick up each day’s meals from the high school.

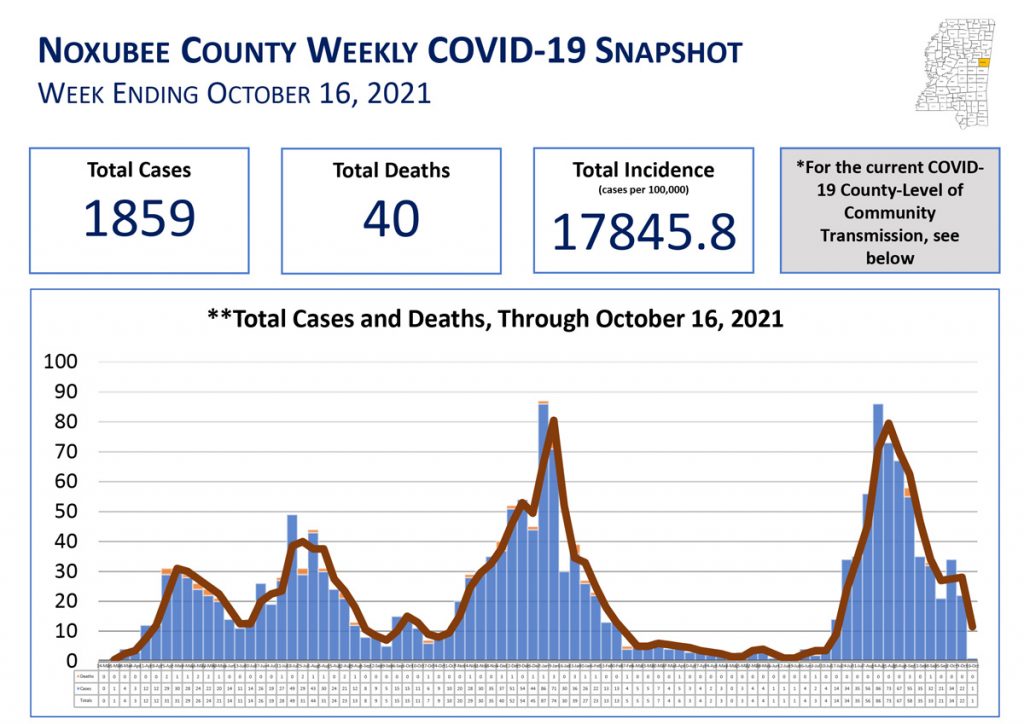

In the fall of 2020, the school district was one of a handful in the state that opted to remain shuttered due to fear of increased COVID numbers upon the return of students to the classroom. As infections in many counties in the state began to level out, Noxubee saw cases in double-digit numbers four days in the last two weeks in July 2020, a trend they had not seen since the early days of the pandemic.

The news was unsettling for those who had struggled through the close of the spring semester. The pandemic wasn’t ending anytime soon.

Cobbled-Together Technology

After schools closed in 2020 and students went home to learn, problems arose even in Noxubee County homes with enough smartphones, laptops or tablets. Households with multiple school-aged children faced the question of how to ensure that each child was logged on for courses. Smaller homes offered little privacy.

“They were all in the same room,” Shawanda Readus said about her three children using their cobbled-together technology to attend school. “You could hear the other teacher talking, and their teacher talking. They are getting distracted by what the other teacher is talking about over here, and then these (children) would get distracted. It was hectic.”

With Noxubee County students consolidated into one district in Macon, many travel long distances for rural areas where there is simply no broadband access and any Internet access can be difficult. By contrast a whiter county like Lincoln in South Mississippi has multiple rural schools in addition to Brookhaven city schools and a seg academy.

Pandemic school closings in Mississippi, thus exposed the usually ignored disparities in rural broadband access, which affect many Black families in particular. In communities scattered on the outskirts of towns, broadband is simply unavailable. Recent census data showed that only 57% of households in Noxubee County had broadband. Like the Readus family, several resorted to using cell phones for classes, but service was often spotty.

Northern Public Service Commissioner Brandon Presley was well aware of issues that rural Mississippians were facing. Presley had garnered bipartisan support resulting in House Bill 366. The bill would allow Mississippi’s member-owned electric power associations or EPAs, which serve about half of the state’s residents, to deliver broadband internet through a subsidiary. Then-Gov. Phil Bryant signed the bill into law in 2019, but the pandemic helped delay the already slow process of providing fiber connections to every home in Mississippi.

“We had a good head of steam built up … but we were just a year into the broadband enabling act when the pandemic hit,” Presley said. “We could not get our ultimate goal done in such a short period of time, and the children were sent home to do their work.”

‘It Was Pretty Devastating’

Then there was the stress of the pandemic, aggravated by disparities embedded into Noxubee County long before the virus arrived.

Travonder Dixon-McCloud recounts the story of one of her students, an 11th grader. The young lady lives in a very rural area of the county with her mother and four siblings. Her mom leaves home for work at 4 a.m. and does not return until 6 p.m., which meant that during the pandemic her daughter was left with the responsibility of caring for her three younger siblings. The high school junior would make sure that her siblings, ages 6, 7 and 9, were logged in and completing assignments. With the added burden, she could not keep up with her own work and stopped showing up for classes. By April, she had been prescribed anxiety meds.

“For about two weeks she just stopped showing up for class,” the school psychologist said. “She said it was too much for her and by not being able to follow what she was doing because she was getting behind was stressing her out. Her anxiety was up. I had to literally go to her house and talk to her about logging back in and talk to her teachers about letting her make up her assignments.”

“(Later) her mom took her to the doctor because she told her that her “nerves were bad,” but she just didn’t have the right terminology. It was anxiety.”

“It was stressful,” Readus agreed about COVID-created education efforts. “I had to get the laptop myself sometimes and try to figure out some stuff. It was basically like a college online class for sixth graders and eighth graders.”

This story was repeated in some form across the district during early months of the pandemic. Parents could not afford to take off work to stay home with their children and were unprepared for the cost of daycare. This meant leaving them home and trusting that the child would log into their classes and complete assignments. Grandparents and neighbors who stepped in to help were thrust into the role of tutor, and parents spent evenings trying to help children who were unable to grasp the material from a figure on the other side of a computer screen that may or may not stay online.

It was a role for which many were unprepared for many reasons.

The most recent census data show that less than a quarter of Noxubee County residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 22% statewide. This meant that a large percentage of parents were not equipped to offer the type of educational assistance that their students receive at school.

Dixon-McCloud has a unique vantage point on the situation. After her initial time as a biology teacher, she left the school district to work for Diamond Grove, a mental health hospital where she fell in love with the field. She later returned to school and earned a master’s in special education with an emphasis in emotional behavior disturbances from Mississippi State University and was recruited back to the district in 2007 as a behavior specialist. She holds a doctorate in clinical psychology from Capella University.

Now servicing the district’s emotionally disturbed students, Dixon-McCloud worries about the mental health of students who would have no outlet from the problems they faced at home during the move to online learning.

“I was looking at the fact that for some kids who I know are in emotionally or physically abusive homes, coming to school is their only relief,” she said. “It is their only break from what they are experiencing at home. So for them to just be at home all the time with constant emotional and physical and even sexual abuse, what was it going to do for their mental health not to have a break?”

A Mental Toll on Teachers

The strain took its toll on staff as well. In August 2020, Dixon-McCloud presented a professional-development session on anxiety and coping in hopes of preparing teachers and staff for the possibility of increased mental-health issues in their students. In attempting to prepare the teachers, however, she discovered another complexity. The weight of educating during a pandemic was overwhelming for school staff themselves.

Teachers struggled with their own fears about the virus and how to navigate a much different school year than they were accustomed to. Many had their own children to consider and faced the logistics of teaching their students while ensuring that their own children had a safe place to attend virtual classes. School leaders experienced mounting pressure from teachers looking for answers and fixes that simply did not exist.

“Everybody (was) stressed to the max,” Dixon-McCloud told the Mississippi Free Press. “After the presentation, I had several of my colleagues to (message) me and tell me, ‘We need, I need this to help us get through this. We need someone to talk to us. We need someone every week or every other week to talk to us and coach us through what to do.’ For everyone, the anxiety of the unknown (and) the anxiety of how to help the kids is through the roof.”

The county already had mental-health challenges with limited access to mental-health care. The 2020 county health rankings shows a 610:1 ratio between mental-health providers and residents in Noxubee County. However, the respondents reported an average of 5.5 mentally unhealthy days in the previous month.

Dixon-McCloud spent the first school year of the pandemic attempting to help staff, teachers and students navigate the emotions they are experiencing. She opened her door to teachers, staff and administrators as they worked to navigate the mounting pressures of the pandemic. She also heard from parents who were feeling the stress and frustration. She now expect long-term psychological and emotional effects of the virus.

“My colleagues and I all believe that the mental-health issues that are going to come from COVID are going to be through the roof,” she said. “Everything is going to be exacerbated. People who didn’t have mental-health issues will develop something whether it’s anxiety, depression, eating disorder. It could even be some type of personality disorder because (they) have been isolated and/or scared.”

It will likely be several years before the full effects of COVID, closed schools and necessary isolation on the mental health of the county’s residents can be fully evaluated. However, it is likely to strain the area’s mental-health services.

Community Counseling Services, which has provided mental-health services to the county for more than 25 years, is a public nonprofit agency partially funded by the Mississippi State Department of Mental Health and governments in the seven counties it serves—Lowndes, Oktibbeha, Clay, Noxubee, Choctaw, Webster and Winston. Most of its funding comes from fees for services that it provides.

Meanwhile, serious illnesses and deaths from COVID continued to plague the county leaving a gaping wound. As of July 14, 2021, the county had reported 1,288 cases and 35 deaths from the virus. McCloud’s uncle, a county supervisor, was one of the area’s first victims. The virus was particularly threatening to the county due to the number of residents suffering from underlying health issues. The 2021 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps report shows that 49.8% of the county’s residents are obese and 30.5% reported in poor or fair health. Noxubee is ranked among the least healthiest counties in the state.

For women like Dixon-McCloud and Brooks, who are committed to living and working in the county, finding solutions to the district’s problems is as essential as breathing.

“We are looking from the outside in, (but) we have professionals or experts in every area we need for this school district to work,” Dixon-McCloud said. “Use these people. Listen to the people who are in the trenches for what we need to do. We need to take what we have and build off that.”

Facing a Second School Year of COVID-19

The doors of the schools reopened in Noxubee County on Aug. 5, 2021. Students poured back into the hallways excited to see friends and teachers, some of whom they had not seen in over a year. The school district, now under the leadership of the state-appointed superintendent Dr. Washington Cole IV, implemented a mask mandate and asked parents to self-report cases and exposures to school employees. Schools implemented a variety of measures including added lunch shifts to increase social distancing and requiring teachers to keep classroom doors open to help with air flow. Still, there was a lingering fear of contracting the virus.

“From teachers and students it is still all anxiety,” Dixon-McCloud said. “Everyone is kind of on edge. It feels different than before we got out in 2020. There is a heightened sense of emotional instability throughout the school.”

Shawanda Readus’ children were among those who returned in August. Within the first three weeks, one of her sons contracted COVID-19.

“He got it from school,” Readus said. “For three days, he had body aches, a runny nose, sore throat, a bad headache, and congestion. I don’t know if it came from football practice or being in the classroom, but (several) of them had it.”

Mississippi State Department of Health statistics from Aug. 31, 2021, showed at least 30 teachers and more than 50 students in the district had tested positive since the start of the school year. However, in a town hall meeting held early in this school year, Superintendent Cole stated that the district had not met the threshold for complete virtual instruction. In early September, parents were asked to complete a survey to gauge interest in a virtual learning option. Because Readus’ children are all athletes, they would have to choose between virtual learning and sports as they cannot do both. After a whole year of virtual instruction, she says that her children would rather be in school.

“They like going and being there because they like being among their friends, but they are also kind of scared at the same time. They don’t want to go virtual,” she said.

However, the delta variant made her wary. “It might be better for them in person, but I don’t like it, especially since the second strand came along and (has) started affecting children more,” Readus said in September.

For teachers, in addition to the fears of contracting COVID, there is the pressure of repairing the damage that a year of spontaneous virtual schooling has caused. A small number of students in the district never logged on to attend classes despite the prompting of school officials. Those students not only failed, but lost a year of instruction.

Other students, despite their best efforts, did not fare as well without a teacher present with them each day. Now teachers must determine the best way to meet their needs leaving the district’s Multi-Tiered System of Supports/ Teacher Support Team (MTSS/TST), education professionals who analyze student referral data and determine appropriate behavioral or instructional interventions, with a tough task.

“Because of software or devices or the Internet, we really couldn’t reach a lot of kids and they got farther behind,” Dixon-McCloud said. “The MTSS and TST teams are really bogged down with a lot of children. There is an influx of transfers from out of state. They are coming in and they are reading or performing below grade level. That coupled with us already being behind is causing an overload for the teachers.”

Seeking Solutions, Leaning on Resilience

Dixon-McCloud continues to meet with students and teachers who are experiencing multiple effects from more than a year of pandemic schooling—though now face-to-face. She has found that in addition to the potential mental-health issues she knew that she would face, students who thrived because they didn’t have to deal with the social anxieties of high school are now exhibiting other problems.

“Some of my clients haven’t had to share space or their thoughts for more than a year. For them to have to come out and do this in front of 25 peers is causing an issue for them,” she said. “I have one student who didn’t initially come to me for depression. She came for other issues but now she is dealing with depression. Now she has both because she can’t deal with coming from home back to school with her peers.”

The pandemic heightened many of the county’s issues with food insecurity, mental health and the educational system. “It stretched the district beyond normalcy,” Dixon-McCloud said. “It stretched the district beyond her comfort zone. I never thought that (we) would be able to maneuver through virtual learning because of infrastructure. And to a certain point, we failed because of infrastructure, but it wasn’t because we really didn’t try. We tried. We tried hard.”

There is one lesson that she hopes that everyone in the district has learned.

“If we plan for or if we are proactive, more people will have the opportunity to be successful,” Dixon-McCloud continued. “Things like this should be included in the school’s crisis plan. We need to plan for something similar to COVID to be a part of a school district’s crisis plan. I think that if we do that we will have a better outcome.

Donna Ladd contributed to this story.

Correction: The above story originally called Travonder Dixon-McCloud the school psychologist, when she is in fact a clinical psychologist. Also, we have corrected Dr. Andrew Mullins’ full title to now-retired assistant to the chancellor and associate professor of education at the University of Mississippi. Due to an editing error, the original story said he was a history professor. We apologize for the errors.

This in-depth Noxubee County historic report is part of the “(In)Equity and Resilience, Black Women, Systemic Barriers and COVID-19” project looking at systemic inequities long facing Mississippi’s Black women and their families and institutions that the pandemic revealed and exacerbated in Mississippi. In upcoming weeks and months, the BWC Project team is publishing what their systemic reporting and numerous solution circles with Black women revealed about three counties (so far): Noxubee (education); Hinds (violence and public safety) and Holmes (health care adequacy and access). The journalists are following up each county overview with specific solutions-journalisms pieces about problems their reporting revealed.

Also see: Jackson Advocate Publisher DeAnna Tisdale’s opening column introducing the BWC Project and reporting collaboration. Visit the full BWC Project microsite here.

This project is a collaboration between the Mississippi Free Press and the Jackson Advocate with support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Write solutions@mississippifreepress.org to offer feedback on the reporting or reach out to Kimberly Griffin at kimberly@mississippifreepress.org if you’d like to sponsor work in additional counties for this project.