The new Texas law that bans most abortions uses a method that Texas and other states employ to enforce racist Jim Crow laws in the 19th and 20th centuries that aimed to disenfranchise African Americans.

Rather than giving state officials, such as the police, the power to enforce the law, the Texas law instead allows enforcement by “any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local governmental entity in this state.” This enforcement mechanism relies solely on citizens, rather than on government officials, to enforce the law.

This approach to enforcement is a legal end-run that privatizes a state’s enforcement of the law. State officials use this method of enforcement to shield themselves from being sued for violating the Constitution, and the law is made, at least for a time, more durable.

The U.S. Justice Department filed suit against the state on the grounds the law violated a woman’s constitutionally protected right to terminate a pregnancy before fetal viability. In its suit, the Justice Department specifically cites one of the cases that was brought over a Texas Jim Crow law that excluded Blacks from participating in primaries, which the Supreme Court struck down in 1944.

Privatizing Discrimination

Following Reconstruction in the South, Texas banned African Americans from voting in party primaries in a law adopted in 1923. This was an example of Jim Crow, a system of laws and customs that institutionalized anti-Black discrimination in the U.S.

When this state law was challenged before the Supreme Court and struck down in Nixon v. Herndon in 1927, the Texas Legislature responded in 1928 with a tricky maneuver much like the current Texas abortion law. Texas repealed the offending statute and enacted legislation that specifically delegated to political parties the power to determine “qualifications of voters in primary elections,” thus seeking to take the state out of the equation.

By putting that power in the hands of private parties, allowing them to discriminate against and prevent African Americans from voting, the state sought to avoid legal rules, based on the Constitution, that required “state action” before a law could be struck down. Essentially, the state contracted out the dirty work of denying Black Texans the right to vote.

In the landmark 1944 ruling in Smith v. Allwright, the Supreme Court “looked behind the law and ferreted out the trickery,” as expressed by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, who argued the case at the court. The court ruled that no matter how “uninvolved” the state of Texas attempted to be, primary elections involved state action sufficient for purposes of a successful lawsuit under the 14th Amendment.

The court concluded that the constitutional right to vote “is not to be nullified by a state through casting its electoral process in a form which permits a private organization to practice racial discrimination in the election.”

Not Giving Up

Democratic Party members in Texas, bent on prohibiting African Americans from voting, turned to yet another privatization strategy to accomplish their objectives.

Since 1889, the “Jaybird Association” in Fort Bend County, a Democratic political organization that was made up exclusively of qualified white county voters, ran its own “pre-primary” to vet and select Democratic candidates for office. Blacks were excluded from these privately run contests. This selection process determined who would run in and likely win the Democratic primaries, which effectively meant only whites would gain those offices.

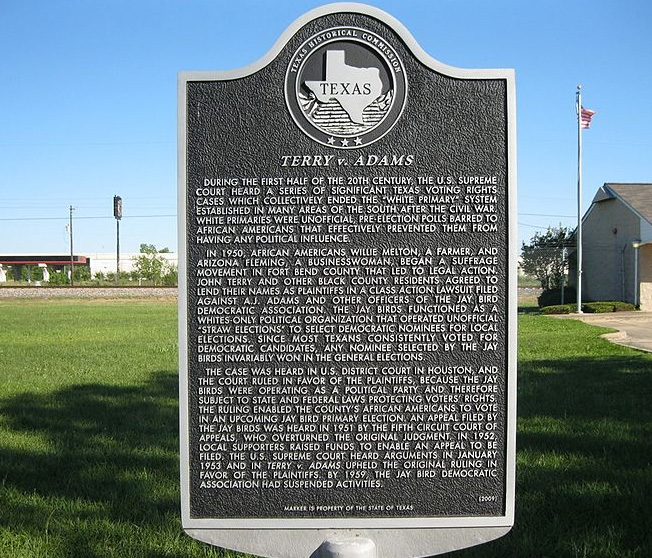

Blacks in the county sued. Yet again, in the 1953 ruling in Terry v. Adams, the Supreme Court invalidated this privately run primary process as a violation of the Constitution. As the court pointed out, the “Jaybird primary has become an integral part, indeed the only effective part, of the elective process that determines who shall rule and govern in the county.”

The court’s ruling invalidated similar privately enforced discrimination in voting in other states, such as South Carolina.

Resurrecting Jim Crow

The new law, formally called the Texas Heartbeat Act, constitutes a similar attempt by the state to privatize enforcement of state policy—all in an effort to prevent legal moves that would stop it from going into effect.

Texas has resurrected a decades-old technique that it used during the Jim Crow era to insulate its discriminatory laws from constitutional review in the courts. And by delegating enforcement authority to private individuals, Texas has transformed its population into a cadre of private law enforcers. Now that the federal government has sued the state over the law, the courts will be in a position to review the constitutionality of the statute.

Nevertheless, the statute raises grave issues about how states go about enforcing their policies. Will Texas voters appreciate that the state has resurrected a Jim Crow-era mechanism to avoid legal responsibility for its policies?

This piece was published in cooperation with The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit publisher of commentary and analysis, authored by academics on timely topics related to their research.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.