The 2021 Mississippi Invitational is the Mississippi Museum of Art’s biggest since the biennial exhibition launched in 1997. Recent works by a whopping 42 artists offer a picture window outlook on the landscape of current art-making in the state, and a sweeping view of the diversity of creativity that continues to spring up here.

Guest-curated by Houston, Texas-based Danielle Burns Wilson, the Invitational’s artworks tie into the themes of these times—resilience, reckoning and reflection.

The show’s range is another strong quality, in the voices, the media, the sizes, even the ages of its artists, with creators in their 20s, their 90s and almost every decade in-between. Threads of the pandemic, social justice, isolation, connection, celebration and home weave through these works, stitching together an evocative exhibition with a surprise around every corner.

The Invitational focuses on visual artists living and working in Mississippi, and is always guest-curated by someone outside of the state. Invitational artists were selected from more than 600 submitted works, and a further narrowing of the field that followed.

“One of the keys that has tied them together, until COVID, was the studio visits,” says Mississippi Museum of Art Director Betsy Bradley. “The guest curator narrows down the field through slides, but then goes and visits the artist in their studio, to see their process, to learn about what their goals are, what they’re trying to accomplish, and then give some feedback. For a lot of these artists, it’s really helpful to have outside eyes.”

COVID-19 upended the usual model. Safety concerns and travel restrictions moved the studio visits to Zoom calls, eliminating drive time and expanding opportunities for more visits and ultimately, more artists. Conducted from home, that brought an ease to the conversations and humanized the process, Wilson says, as professional and personal lives seemed to merge. “It was quite refreshing,” she notes in a conversation with artists, also via Zoom.

Because of the tumultuous events of 2020—COVID-19, the lockdown, the public murder of George Floyd and more: “I knew my curatorial focus … was going to have to be different from my predecessors,” she says. “It had to be. I felt remiss if this Invitational didn’t reflect the voices and experiences of this moment,” Wilson continues.

“Art has always been an integral part of really redirecting struggles and showing progress and it’s my hope that this exhibition really does that.”

Water Valley textile artist/quilter Coulter Fussell is the recipient of the Jane Crater Hiatt Artist Fellowship, a $20,000 grant awarded to one artist in the Invitational. Her 10-by-8-foot quilt in the show, “Home,” turns scraps and their attendant stories to a new purpose. With a concept of transient living, fabrics suggest the elements needed to feel right at home—bed, lamp, window, TV, curtain—plus a suitcase to pack the room up for travel. Half a lampshade, an open suitcase and the folds of a damask “curtain” bring a 3-D quality into the mix.

Fussell makes art from the fabric donated by townspeople. It’s free, plus “I really like the life that comes with textiles that have already been used,” she says, with variations in color and texture that add to the painterly effect. “I use quilting as storytelling, and when you use found materials, there are stories already attached to your materials. You can see evidence of lives already lived. Including that is not just a bonus. It’s really essential.”

With the fellowship, her aim is a series of more sculptural quilts that, when viewed through different light spectrums—3-D, infrared, shadow-casting techniques—reveal more. “I’ll make some super weird quilts,” she says, chuckling. “That’s the long and short of it.”

Christina McField of Jackson also sees the stories of past lives in the subjects she turns her lens toward. Abandoned spaces show the ravages of time and neglect, and also the slow creep of nature as vines snake across the stands in a gymnasium or claim the roof of a dilapidated old house.

For McField, they hold adventure, connecting to childhood memories and sparking curiosity about those who once lived in and loved those places. “They connect me back to my mother and nature. … I feel like most people don’t look at these spaces, they just drive by them. But, they’re treasures to me,” she says. “I find people’s lineage through these spaces.”

Racial reckoning and reclamation, and pandemic isolation are topics surfacing in Brenden Davis’ artworks, in imagery that holds tension and commands a closer look. A smiling Black figure—akin to disparaging stereotypes of an earlier age—is turned into an image of strength and perseverance. In “I Can Hardly See,” he radiates a tremendous light, almost like a shield, at a nighttime gathering of klansmen.

In “Wanting to Go,” a figure reaches toward the door, but stays within walls that show the countdown of days. “I was really trying to explore more emotions in my art,” says Davis, a recent Millsaps College grad. He described that “stuck-in-your-own head” feeling that lockdown brought, as negative imagery continued to come through media, while the comfort of community was beyond reach.

Will Jacks’ silver gelatin print of willow branches drapes from the ceiling, “shading” a bench and continuing across the gallery floor in both directions—about 50 feet long, total. An accompanying video shows the work actually in the willow tree that supplied the branches, swaying in the wind. “I’ve been thinking a lot about documentary photography, and how that really shapes perception and understanding of place,” says Jacks, of Cleveland.

This is a different way to document. Jacks describes how, armed with spray bottles of developer and fixer like pistols, he’d walk back and forth on the print, responding as the image emerged—somewhat like Jackson Pollock’s action painting. “I want people to look at this and not be sure what it is,” he says, hoping to open a small window for viewers to question other things. “It’s also about pushing the envelope of, what is a photograph?”

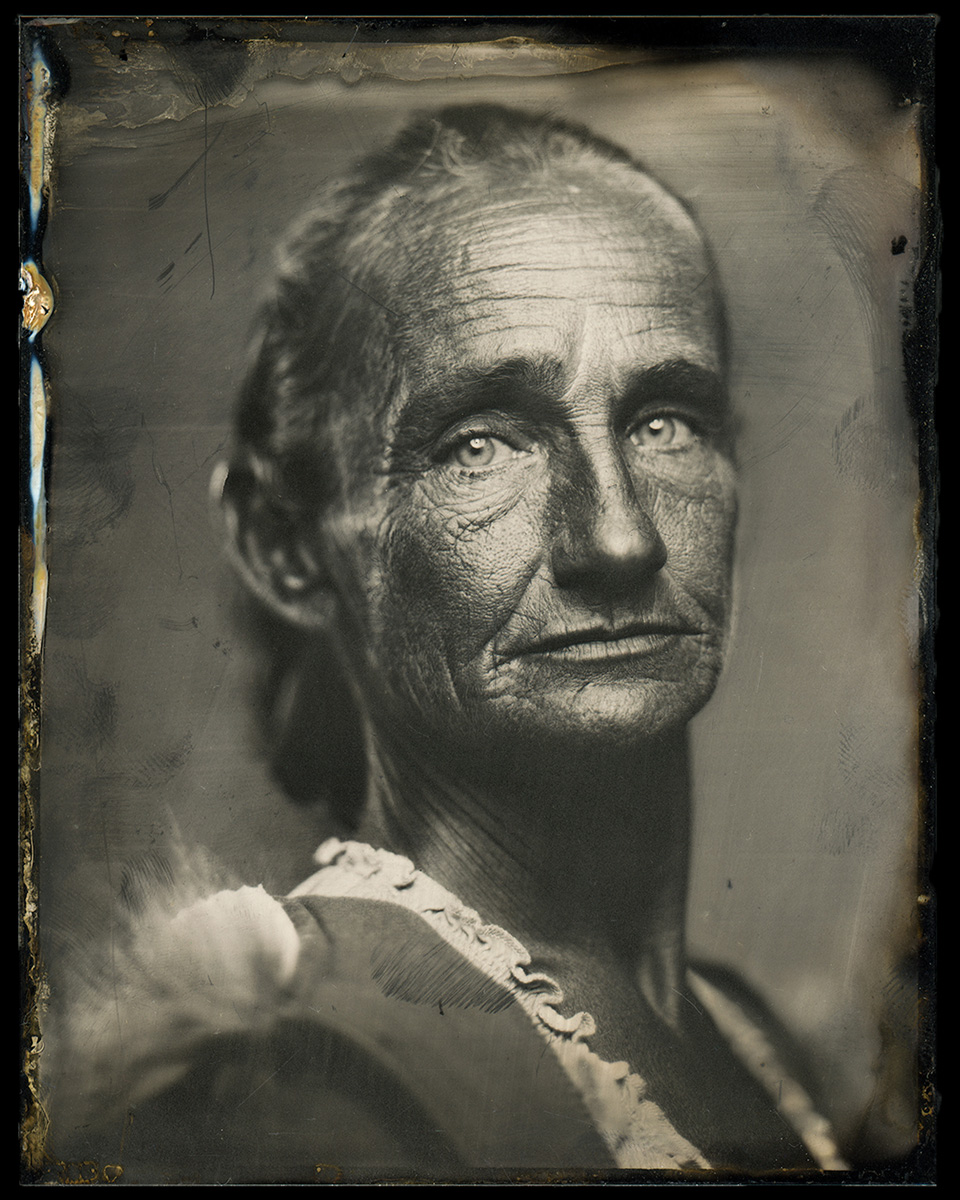

“So, Will has the largest, and I have the smallest piece in the show,” says Michael Foster, whose tintype “Rejeana L.” seems as much a salute to photography’s past as his friend’s 50 feet of photo edges into new territory. Foster had spotted his subject at the Loblolly Festival in 2014, and he talked her into sitting for a portrait. “It’s probably the most honest portrait that I’ve ever made,” he says. Her visage could be from another age, gazing across centuries with a timeless truth.

Norma Bourdeaux’s small diptych, “Bon Secour II,” also invites a closer look, this time rewarding with a river scene so intimate it could be a memory tucked in your back pocket, and so calm it works like a balm. “You can’t ride up and down that river without thinking everything you look at is gorgeous,” she says of the Alabama scene.

In sculptor/artist Lawson King’s works, the seemingly playful hands and balloons imagery becomes a symbol of something deeper. In decision-making or in the wake of trauma, we have to learn what to hold onto and what to let go of, in order to heal and grow, he says in the Zoom conversation with artists. “The balloon, to me, kind of represents a goal or an idea that you’re entangled with. … It’s kind of like being OK with the unknown.”

Old work pants turn into handmade paper flags in Kristen Tordella-Williams’ art, which speaks of labor’s imprint, feminism, the environment and more. “Labor connects us, more than divides us,” she says of the flags’ range of hues. There’s a celebratory air as well, in these banners to hard work, and to the process of taking something old and useless in a new direction.

The expanse and the resilience of Mississippi’s artistic community, particularly with so many participants in the exhibition, come as welcome reassurances, the artists say. Introductions are made, bonds strengthened, ideas sparked and networks formed.

The guest curator’s outlook often brings a fresh focus on artists who may be new to viewers, new to each other, and even new to the museum.

“In every single one of these since I’ve been here, we’ve learned about artists we didn’t know about before, and that’s really exciting,” Bradley says.

The Invitational is on view at the museum through Nov. 7. Tickets are $15 adult, $13 senior and $10 student at msmuseumart.org. free for members, for children ages 5 and younger, and for K-12 students on Thursdays. As a partner in Art Museum Month, admission is free during August; register and find out about other participating institutions in the state at visimississippi.org/artmuseums.