Accusations of a physician in rural Georgia sterilizing women in a U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement center came to light in 2020. While these procedures shocked many, women of color in the rural South have faced this reality at the hands of the state and individual physicians for well over 50 years. Like many of these women, the victims in the Georgia immigration center say they faced similar approaches to their ultimate sterilizations—and their alleged abuser and supporters use the same language and reasons to justify their violations of human rights.

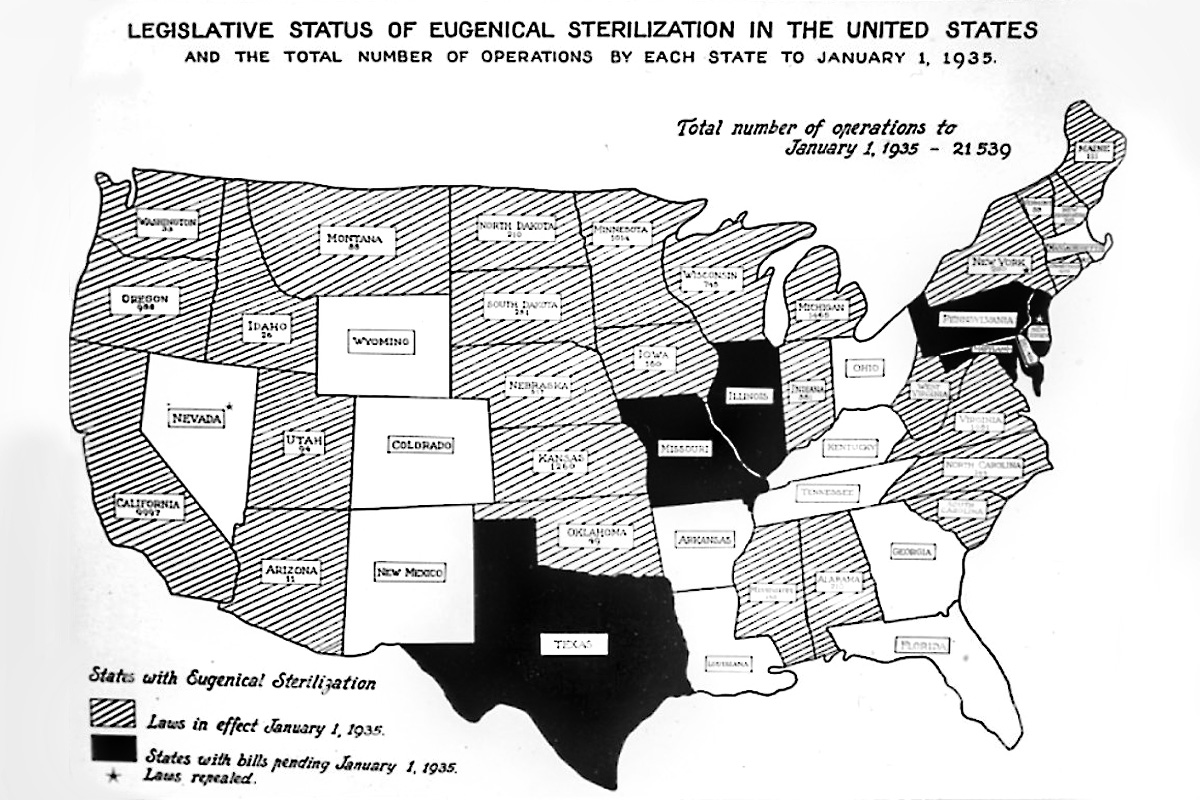

In the 1950s, as the Civil Rights Movement’s momentum grew, southern politicians, local officials and medical personnel began embracing the use of sterilization to maintain their white-supremacist hold in the slowly eroding Jim Crow South. While maintaining a stranglehold on political power in the region, state legislators proposed sterilization bills that would, as Rep. Ben Owen of Columbus, Miss., put it, “stop this black tide which threatens to engulf us.”

The main argument legislators used to defend their legislation centered on early forms of coded language concerning who should and should not have children, specifically those on government assistance.

Both North Carolina and Mississippi passed forced-sterilization legislation. On two separate occasions, in 1957 and 1959, the North Carolina Assembly pursued sterilization laws that largely targeted Black women. State Sen. Wilbur Jolly introduced a sterilization bill that he argued would put an end to the “profession” of having numerous children out of marriage and receiving government assistance. The Senate defeated the bill 32-2.

Two years later, Sen. Jolly and State Rep. Rachel Darden Davis of Lenoir, N.C., a physician, reintroduced similar legislation that gave the state authority to sterilize women with more than two children out of marriage. While holding a public hearing on the bill, Sen. Jolly, pointing and shaking a finger at a group of African American audience members, proclaimed: “One of every four of your race born in North Carolina is illegitimate. … You ought to be concerned about it.”

While the legislation gained pushback, it ultimately passed, but made having two or more children out of marriage a misdemeanor.

‘Submit to Sterilization in Lieu of Imprisonment’

On three separate occasions, the Mississippi Legislature attempted and eventually passed sterilization legislation similar to North Carolina’s bill. Mississippi legislators proposed bills that would force unwed mothers and particularly those on government assistance to succumb to forced sterilization by the State. While defending their legislation, the bill’s proponents rooted their arguments in deciding who and who should not have children by saying they sought “to stop, slow down, such traffic at its source” and to sterilize “the mother of every baby delivered at state expense.” None of them made it past cloture.

On the eve of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Mississippi Legislature passed a bill that would have made having children out of marriage a felony. Violators of the proposed law would have to choose between serving a one-to-three-year prison sentence or “submit to sterilization in lieu of imprisonment.”

Much like the North Carolina legislators, those in Mississippi based their arguments on claims about who is fit to have children, specifically those on government assistance. Rep. Walter Meek of Eupora, Miss., said that “the State of Mississippi is subsidizing illegitimacy through welfare payments, and that the moral structure has completely broken down in some segments of society.”

After downgrading the penalty from a felony to a misdemeanor, and punishable by 30 to 90 days in jail and up to a $250 fine, House Bill 180 passed the Mississippi Legislature.

‘I Don’t Think You Need Any’

Even after the passage of civil and voting rights legislation, and the expansion of the federal safety net, women of color in the South continued to fall victim to state agencies and medical personnel. While President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society undoubtedly assisted millions of Americans, it fell victim to the same perils as the New Deal—allowing continued state and local control of programs—and ultimately hurting the same people it meant to help.

One of these programs was the federally funded Montgomery Family Planning Center in Alabama.

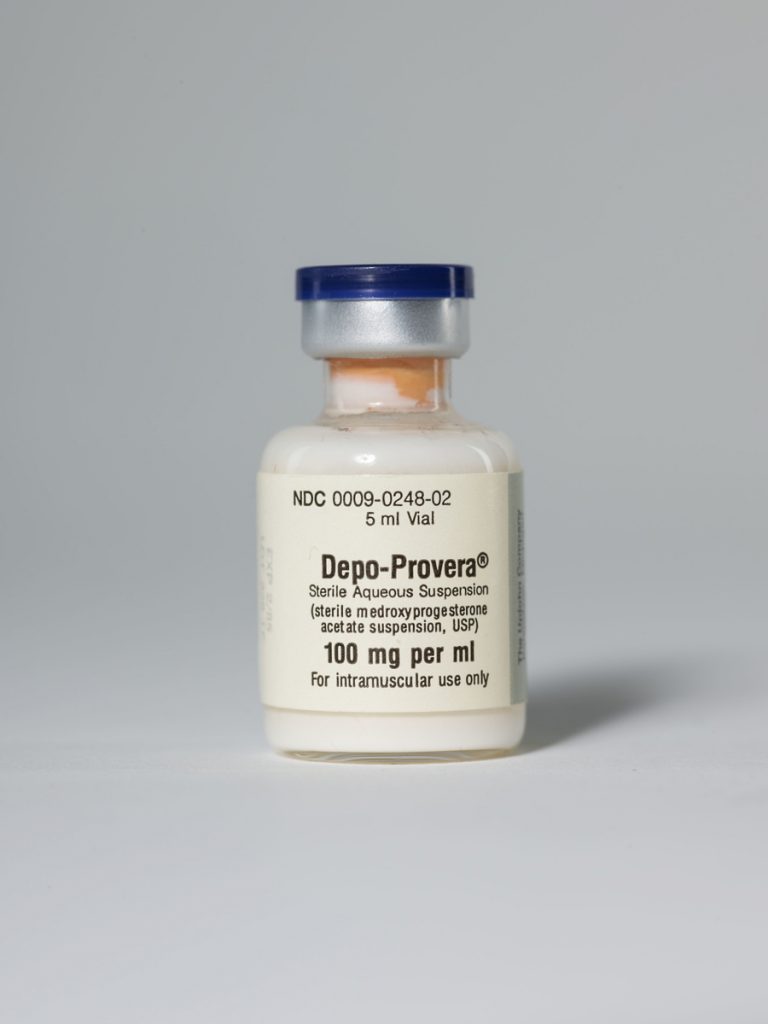

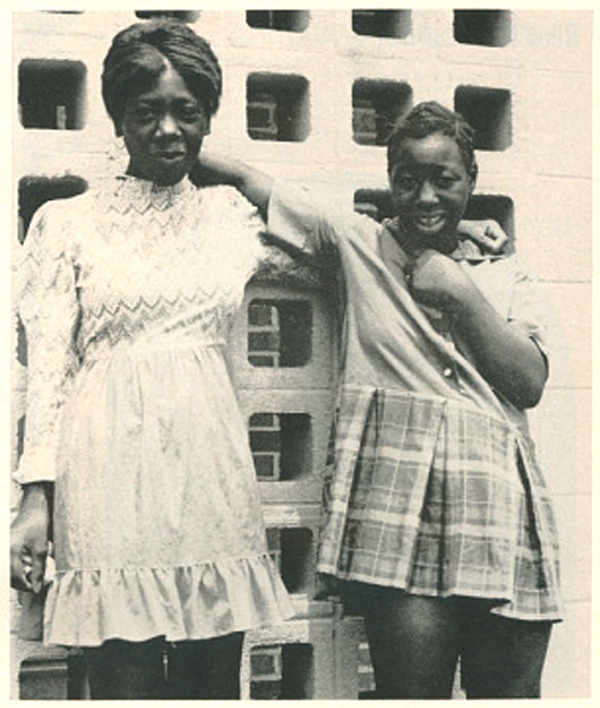

In June 1973, 12-year-old Mary Alice Relf, and her sister, 14-year-old Minnie Relf, underwent involuntary sterilizations at the hands of local health officials and surgeons associated with Alabama’s MFPC, funded by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and the Office of Economic Opportunity. Even before their sterilizations, the Black girls, along with their older sister Katie, had been receiving rounds of Depo-Provera, a birth-control medication never formally approved for this purpose by the Food and Drug Administration due to producing cancer in test animals.

After Alabama officials coerced the girls’ illiterate mother into approving the sterilizations, they drove the girls to their fate. They then returned to the Relfs’ government-subsidized apartment attempting to coax Katie to also undergo an unwanted sterilization. Upon their arrival, Katie locked herself in her bedroom and told the local health officials that she wanted children. One official replied, “I don’t think you need any.”

Weeks later, in Aiken, S.C., reports of numerous Black women on government assistance and pregnant with children out of marriage receiving sterilizations at the local community hospital arose. Dorothy Waters, a Black woman separated, pregnant and on government assistance, reported that Dr. C.H. Pierce coerced her into receiving a sterilization upon birth of her child.

“Listen here, young lady, this is my tax money for this. I’m tired of these ladies going around having babies. If you won’t have this you can find yourself another doctor to deliver your baby,” Mrs. Waters quoted Dr. Pierce as saying. Another woman, Mrs. Virgil Walker, a married mother of four children, corroborated Mrs. Waters’ story. Dr. Pierce threatened that Mrs. Walker would be taken off the “welfare rolls” if she did not consent to a sterilization upon the birth of her forthcoming child. While coercing women into sterilizations, Dr. Pierce also reaped more than $60,000 from Medicaid during an 18-month period from 1972 to 1973.

Supporting the actions of Dr. Pierce and two other obstetricians—Dr. Niles A. Borop Jr. and Dr. Kenneth N. Owens—a group of citizens in Aiken County named the Silent Majority, began circulating a petition supporting their actions. It read, “We believe it is unfair to the taxpayers and the children of the welfare recipients for their parents to continue having children. We feel the children of welfare families would be better cared for if the number of the family were limited. … We believe in such cases, sterilization should take place.”

The group planned to get 5,000 signatures for the petition, then send it to local, state and federal politicians along with a request for enactment of legislation requiring sterilization of maternity patients on government assistance with three or more children. However, they were unsuccessful.

William R. Bland, a local pharmacist who headed the organization, argued that “people like her (Mrs. Carol Brown, a victim of Dr. Pierce) should not have any more babies if the taxpayers have to pay for them.” He continued, “Taxpayers have the right to say whether their taxes will pay to support large welfare families.”

Dr. Amin: ‘The Uterus Collector’

Forty-seven years later in September 2020, reports of women in the U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement custody in a rural Georgia detention center receiving unwanted hysterectomies by a local obstetrics and gynecology specialist came to light.

Dawn Wooten—a nurse who worked at the Irwin County Detention Center run by La Salle Corrections, a private for-profit company—filed a whistleblower complaint with the Department of Homeland Security about the conditions, rate of COVID-19 among detainees and the hysterectomies that Dr. Mahendra Amin performed on immigrant women at a local hospital. With Georgia-based advocacy groups Project South, Georgia Detention Watch, Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights in the South and the South Georgia Immigrant Support Network, Wooten filed a 27-page report alleging not just coerced sterilization, but also using immigrant women as experiments.

“We’ve questioned among ourselves like goodness he’s taking everybody’s stuff out … his specialty, he’s the uterus collector. … Everybody he sees, he’s taking all their uteruses out or he’s taken their tubes out.”

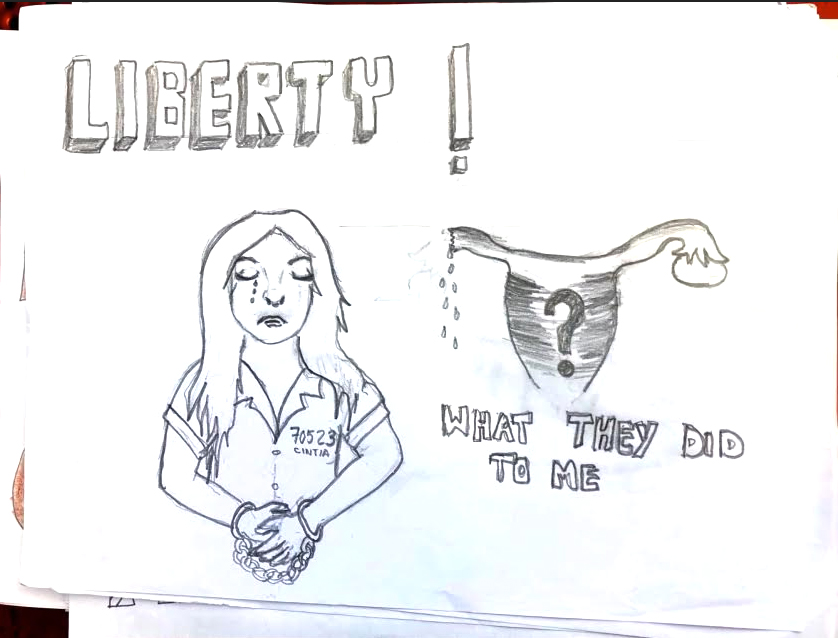

Fast forward two months later, and more than 40 other women detained at the center accused Dr. Amin of medical abuse. The women also accused the center of retribution, as severe as deportation, for speaking out on the unwanted hysterectomies and other medical procedures.

In their legal petition, the women were “victims of non-consensual, medically unindicated and/or invasive gynecological procedures … performed by and/or at the direction of (gynecologist Dr. Mahendra Amin).” The petition continues that “In many instances, the medically unindicated gynecological procedures Respondent Amin performed on Petitioners amounted to sexual assault.” As one detainee noted, “I thought this was like an experimental concentration camp. It was like they’re experimenting with our bodies.”

In response to these allegations, a supporter of Dr. Amin created a Facebook page with members including patients of whom he has delivered their children. Many of the posts center around selling merchandise in support of the doctor, personal stories and the group administrator warning others against talking to the media. Much like the “Silent Majority” that defended Dr. Pierce decades before, some of the members’ comments on the page vehemently defend Dr. Amin while flippantly dismissing the detainees’ serious allegations.

Furthermore, the page’s administrator has referred to those at the detention facility as “immigrants [sic] and inmates who were charged with crimes,” implying justification for the unwanted hysterectomies and other procedures.

On Thursday, May 20, 2021, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, at the request of the Biden administration, ordered ICE to dissolve all contracts with the Irwin County Detention Center, which is privately run by the county, “as soon as possible.” One can guess that a major reason for ceasing all contracts center on the fact that the facility is under federal investigation for abuse allegations like forced sterilizations.

Secretary Mayorkas, in a memo to ICE, stated “We will not tolerate the mistreatment of individuals in civil immigration detention or substandard conditions of detention.” He added that the DHS has “an obligation to make lasting improvements to our civil immigration detention system.”” Secretary Mayorkas finished his memo by reiterating the difference between the Trump and Biden administrations’ handling of immigration centers. “This marks an important first step to realizing that goal. DHS detention facilities and the treatment of individuals in those facilities will be held to our health and safety standards. Where we discover they fall short, we will continue to take action as we are doing today.”

The unwanted sterilization of women of color by the state and individual practitioners, defended by the coded language of who should and should not have children, has a long history in the South. The stories of these women at the rural Georgia detention center only reiterates this long, troubling history of controlling women of color’s bodies, and viewing their fertility as a bane on society and the economy.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.