Frederick Pritchett was 17 when he learned he was going to prison for 55 years for armed robbery, kidnapping and motor vehicle theft.

Less than a month after his initial Nov. 29, 2012, sentence, he was charged with aggravated assault on a law enforcement officer and robbery involving an incident while in custody at the Lauderdale County Detention Center. The teenager was later convicted and given the additional 45 years bringing his sentence to 100 years.

Now, Pritchett is expected to leave prison in 2111 for crimes he committed as a teenager. By then, he’ll be 116 years old—if he lives that long. He didn’t even kill somebody.

A female correctional officer said Pritchett asked for a cup of water and when she opened the cell door to hand it to him, he grabbed her arm, initiating a struggle. She said the teenager choked her. The confrontation lasted about one minute and 15 seconds before Pritchett released the guard. Her cellphone was later found in Pritchett’s cell.

Aging Out of Criminal Conduct Behind Bars

Now 26, Pritchett is one of 370 Mississippi inmates serving virtual life sentences, meaning they are on the inside for 50 years or more. Of those “virtual lifers,” 22 were juveniles like him when they committed the crimes that led to their incarceration, as a recently released national report “No End in Sight: America’s Enduring Reliance on Life in Prison” by The Sentencing Project revealed. In addition, Mississippi has 2,041 incarcerated people serving life sentences, with 1,600 of them serving life with parole, Mississippi Department of Corrections data show.

The Sentencing Project report said lengthy prison sentences ignore the fact that most people who commit crime, even those who have committed a series of crimes, age out of criminal conduct. The people most at risk for committing crime are those in their late teens to mid-20s, Sentencing Project Senior Research Analyst Ashley Nellis, author of the report, said.

〈MFP seeks to sustain the most diverse and inclusive statewide media outlet in Mississippi. Click HERE to Donate to our Truth-to-POWER Campaign!〉

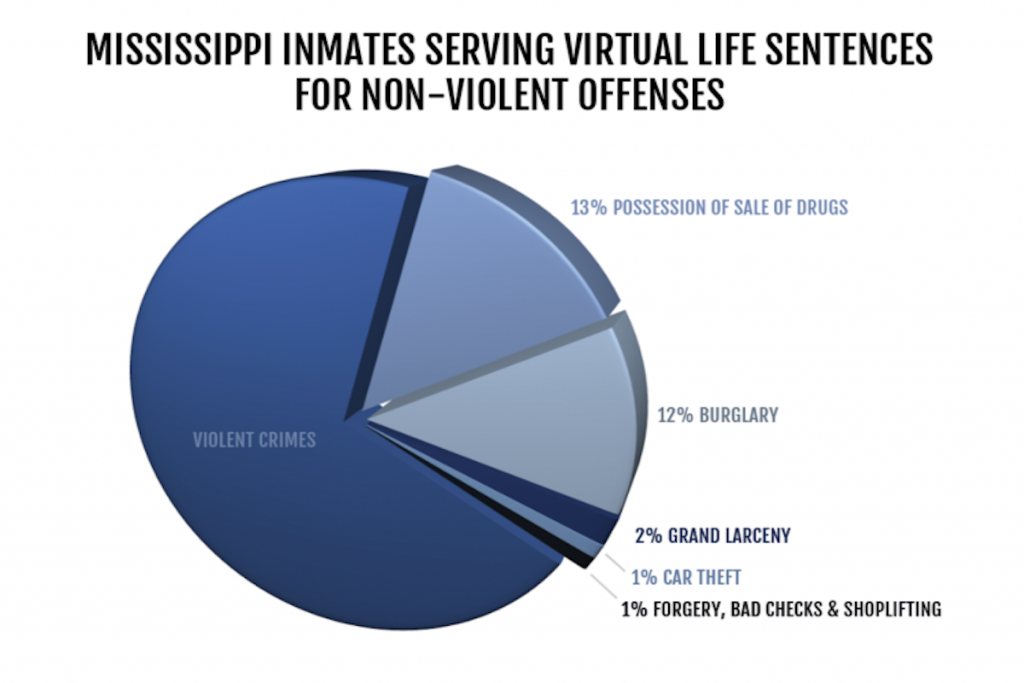

A data analysis shows that many of those serving 50 years or more were not convicted of violent offenses. For instance, 13% of those sentenced were for the possession or sale of drugs, 12% for burglary, 2% for grand larceny, 1% for car theft, and 1% for forgery, bad checks or shoplifting.

Convictions involving homicides made up only 4% of those serving violent crimes. Other major categories included 15% for rape and other sexual assaults, 10% for assault, 10% for armed robbery and 6% for kidnapping.

Pritchett’s attorney argued on appeal that he should have faced no more than a simple assault charge in the case. However, the Mississippi Court of Appeals refused to dismiss his conviction.

He was sentenced as a habitual offender, meaning he will have to serve most of the sentence before being eligible for parole.

“We have concerns about any extreme sentence. That is particularly true when the person was a juvenile at the time of the offense,” Mississippi State Public Defender Andre de Gruy told the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.

De Gruy said he and other juvenile-justice advocates have been working in the courts and Mississippi Legislature since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision in response to minors sentenced to life without parole. The court ruled mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles were unconstitutional and should be reserved for the rare juvenile offender who is “permanently incorrigible.”

Sentences Guaranteeing Death in Prison

Jonsha Bell was sentenced to a total of 95 years in prison, without the possibility of parole or earned release, for non-homicide offenses he committed on June 1, 1994, when he was 17.

Bell was convicted of armed robbery, burglary and two counts of kidnapping and sentenced as a habitual offender.

Jake Howard, an attorney with the MacArthur Justice Center in Mississippi, filed an appeal to the Mississippi Supreme Court arguing the 95-year total sentence deprived Bell of the meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation, which the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Mississippi Constitution require for juvenile non-homicide offenders.

“Mr. Bell’s aggregate sentence guarantees that he will die in prison,” Howard argued.

The Mississippi Court of Appeals rejected Bell’s appeal, and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the case.

De Gruy said due to the many sentenced before Miller and still more facing life without parole for new offenses, his office simply has not had the capacity to look into virtual life sentences.

Gov. Tate Reeves signed a law providing parole eligibility for some youthful offenders this year. “There will still need to be a lot of work done in the courts and the Legislature regarding how we treat juveniles in the criminal legal system as well as the Youth Court system, but meaningful parole eligibility would be a good start,” de Gruy said before the governor signed the bill into law.

Senate Bill 2795 grants parole eligibility for more inmates including those convicted of armed robbery after serving 60% of their sentence or 25 years, whichever is less. The bipartisan bill also allows nonviolent offenders to be eligible for parole after serving 25% or 10 years for offenses that occurred after June 30,1995.

The legislation does not mandate parole. It only allows a parole hearing before the Mississippi Parole Board. Last year, Gov. Reeves vetoed a sentencing reform bill, saying it could lead to parole for those convicted of murder and sex crimes. This year’s bill does not allow parole eligibility for those convicted of murder and sex crimes.

However, the new law likely will not have much impact on virtual life sentences because it not include parole eligibility for habitual offenders. The majority of those serving long, cumulative sentences are labelled as habitual offenders.

Across the country, states face the contradiction of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that mandatory life without parole for juvenile offenders is unconstitutional while having sentencing laws that amount to virtual life.

Under Tennessee law, life without parole is 60 years. The minimum sentence for life with parole is 51 years, the longest in the country.

When Eligibility for Parole is Meaningless

The case of Cyntoia Denise Brown was intended to be a test balloon for other juvenile offenders in state prisons serving virtual life sentences. At 16, she was sentenced to life with parole for killing a man she said hired her for sex.

The Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals upheld the sentence. Brown appealed to the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee, saying 51 years violated the findings in the Miller ruling. The court denied relief because the Miller decision prohibits mandatory life without parole for juvenile offenders, and Brown received a life sentence with parole.

In 2018, Brown’s lawyers challenged her sentence in federal court, saying it violated the spirit of U.S. Supreme Court rulings limiting life sentences for juveniles.

Her appeal was never heard. In January 2019, Gov. Bill Haslam granted Brown clemency, rendering her appeal moot and leaving the constitutionality of Tennessee’s 51-year life sentences for juvenile offenders an open legal question. Brown was released on Aug. 7, 2019.

Following the Miller ruling, South Dakota eliminated life without parole for juvenile murderers, but the state’s high court has upheld virtual life resentences.

A similar situation occurred in Nebraska where lawmakers overhauled the state’s sentencing laws in 2013 in response to Miller.

In May 2013, the Nebraska governor signed LB 44 into law. It set a new sentencing range of 40 years to life for those who commit first-degree murder or kidnapping. However, some of the affected inmates were given such long prison terms that they are effectively life sentences. Two got 90 years to life; one got 80 to life; one got 70 to life; and one received two consecutive sentences of 45 to life.

Is A De Facto Life Sentence For Juveniles Unconstitutional?

Some of the others serving virtual life sentences in Mississippi prisons include:

Edward Lamont Neal is serving 95 years for a string of crimes that began with malicious mischief. Initially sentenced to five years for that offense and five years for jail escape in Lowndes County, he was then convicted of burglary of an unoccupied dwelling and given 25 years in prison. Later, Neal was given 60 years as a habitual offender for armed robbery and aggravated assault. His tentative release date is 2098.

Steven Thomas was sentenced to 70 years in prison after pleading guilty in 2007 in Madison County Circuit Court to kidnapping, forcible rape and armed robbery. Thomas, 17 at the time, confined a male in an office in Canton and a woman in a closet, forcibly had sex with the woman and took $20 from her. Thomas said in his own court petition last year to the Mississippi Supreme Court that his young age at the time of the offenses, difficult childhood and history of substance abuse made him less culpable than a similarly situated adult offender. He asked for an evidentiary hearing and argued his sentence was cruel and unusual punishment. The court denied his petition.

Michael Cochran was 15 when he was charged with attempted armed robbery and aggravated assault in June 2002. He was 16 when a Coahoma County Circuit Court jury convicted him and he was sentenced to two 50-year terms and one 20-year term. The sentences run concurrently but the 50 years to serve is without the possibility of parole.

James Wash was 16 when a judge sentenced him in 1999 in George County to a combined 60 years without parole for aggravated assault and armed robbery. He has now spent more than half his life in prison. His release date is 2058 when he will be 77 years old. In a court petition to vacate Wash’s sentence, his attorney argued the only way he will complete his sentence is if he exceeds his life expectancy by nine years. “It’s a de facto life sentence,” said his attorney Ross Parker Simons.

Simons said recently he still represents Wash, who is now 39.

“I believe that any non-reviewable de facto life sentence for a minor is unconstitutional,” Simons said of his reason for continuing to represent Wash pro bono.

Simons hopes the Mississippi Supreme Court or the United States Supreme Court eventually will prohibit a non-reviewable de facto life sentence for a minor (one that exceeds natural life expectancy).

Simons said some state supreme courts have found that such sentences violate the Eighth Amendment and have remanded cases back to lower courts for new sentencing hearings, but Mississippi is not one of them.

New Jersey is among the states that have applied the U.S. Supreme Court rulings to virtual lifers.

On Jan. 11, 2017, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. Supreme Court’s findings in Miller apply “with equal strength to a sentence that is the practical equivalent of life without parole,” as ”[t]he proper focus belongs on the amount of real time a juvenile will spend in jail and not on the formal label attached to the sentence.”

Although the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t take the Wash case from Mississippi for review, Simons is waiting for the court to take a similar case and hopefully decide in the defendant’s favor.

MCIR Managing Editor Debbie Skipper contributed to this report.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism. Sign up for their newsletter.