When Gerald Sander began working at Monroe Tufline Manufacturing in Columbus, Miss., in 2017, he received a starting salary of $8 an hour. At first, Sander felt this was fair—after all, he had located the job through a “temp agency,” a type of company that helps unemployed Americans find short-term jobs.

Six months later, Sander was still making $8 an hour, despite the fact that he had long outstripped the 10 weeks that a temporary worker is expected to stay on a job. Motivated by his need to provide for his young child, Sander says he approached the management of the plant to ask a difficult question: “I ain’t tryin’ to offend nobody, but is it the color of my skin?”

It was a fair question, as the National Employment Law Project claims that “Black and Hispanic workers are overrepresented in nonstandard work with the lowest job quality,” with each group comprising over one-quarter of the temporary workforce in the United States. Monroe Tufline Manufacturing responded by giving Sander 50 cents more an hour, still short of the dollar-an-hour raise their “non-temporary” employees received.

It was a distinction Sander could not understand, as he no longer considered himself a temporary employee. Two years passed, and Sander, who was now the father of three children, could no longer justify making just over a dollar more than the federal minimum wage, which has not seen an increase since the first year of the Obama administration.

Sander again went back to the management staff, this time with a warning. “Either keep me on, or I’m walking out today,” he told them simply.

Again, his management resisted losing an experienced employee, and Sander finally moved into a double-digit salary, at last making $10 an hour after 30 months on the job. Within six months, the $10 transformed into $13, but at that point, pay stagnated. “I’m still looking for a raise,” Sander admitted during the Southern Workers Safety and Health Summit. The Mississippi Workers Center for Human Rights hosted the summit Saturday, April 24th, in conjunction with the National Employment Law Project.

“But it ain’t came yet.”

‘Trading Dignity for a Paycheck’

Sander’s story was not unusual during the three-hour seminar, as the multi-person panel, composed entirely of current or former temporary workers of color, shared their experiences with unfair and often unsafe labor practices in Mississippi and in surrounding states.

“(These problems) are because of greed and callous disregard,” host Jaribu Hill stated during her opening remarks. “The system of capitalism robs the poor and forces them to trade dignity for a paycheck.”

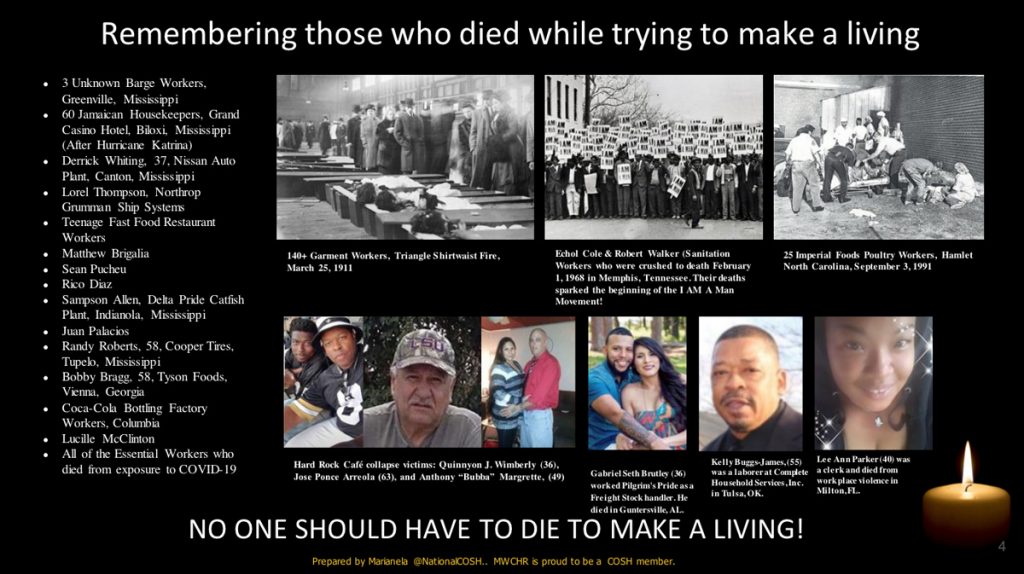

These deprivals of dignity took myriad forms. The keynote speaker, Floridian Antonia Washington, spent five years as a temp worker for the same agency that located a job for her brother, Day, who died 90 minutes into his first shift at Bacardi. Nita Carter nearly lost a finger in the kitchen at a Shoney’s in the Mississippi Delta but was simply told to “wrap it and get back to work;” LaKisha Thomas laundered bloody and bedbug-infested sheets at a Greenville, Miss., linen company that failed to provide adequate protective gear.

Despite their varied experiences in the workforce, all of the temporary workers agreed that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic made their working conditions immeasurably worse.

From Bad to Worse: COVID Complicates Low-Wage Jobs

Rickey Thompson, a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives, went back to work at a long-term-care facility in the northern part of the state when the Mississippi Legislature ended its session early after a suggestion from state health officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs.

“It was a struggle for me,” Thompson acknowledged, saying that the facility provided its staff—which Thompson noted was largely composed of young Black females who were “doing what they had to do”—with a single mask for the entire week. He partially blames this institutional neglect for the fact that he and his wife both contracted COVID later that same year.

Although other panelists agreed that much of the reason for hazardous working conditions during the pandemic was the failure of businesses to protect their employees, many of them said that their customers disobeyed city- and state-wide mask ordinances.

“They closed everything (in Greenville) but Walmart, Lowe’s and the golf course,” remarked Rebecca Miles, who works at the city’s public golf course. These closures did not prevent most of the golfers from coming to the course without masks, and Miles’ pleas for the management to enforce masking mandates fell on deaf ears.

Eventually, Miles and Thomas, whose employers at the former Broadway Linens had failed to provide masks and to enforce social-distancing restrictions among its employees, stood on the steps of Greenville City Hall, demanding protections from the city. Eventually, the city responded by initiating a city-wide mask mandate, which Hill says is owed to the women’s persistence.

‘We Have to Hold Them Accountable’

The panelists concluded the summit by lauding Miles’ and Thomas’ determination to instigate change in their Delta town, saying that temporary workers were their own best (and often only) advocates in the face of workplace injustice.

“These companies should be held accountable,” Washington said. “But we have to hold them accountable.”

Sander echoed her sentiment, citing the many times he had to approach Monroe Tufline’s administration in order to receive more equitable treatment and pay. “You gotta know your own worth,” he said before leaving the Zoom call to return to work at the same plant that, four years on, is still reluctant to accept his non-temporary status.

Others, though, insist that much of the best work of advocacy can be done from the outside, a safe distance away from the industries that often stand idly by as 5,000 workers a year die on the job. Nita Carter agrees with that assessment, as she left the Shoney’s that maimed her hand and sought a degree in social work from Mississippi Valley State University.

“Now, I stand in the gap for workers who are injured and for justice and for rights,” Carter said.

Those who are interested in guaranteeing additional rights for workers and protections in workplaces across the state can reach out to the Mississippi Workers’ Center for Human Rights by visiting (LINK) https://www.msworkrights.org/get-involved. The program’s next summit is slated for Dec. 9-11, 2021, though no location has yet been determined.